Habitual Dismissals of Meritorious Cases Are Tearing America ApartOverwhelming Workload in 2020 Accelerated Habitual Dismissal Behavior in U.S. CourtsAUTHOR’S NOTEThe information herein elucidates the single most important issue facing the survival of the United States as a nation and a society. This paper is the basis for my Petition for Writ of Certorari to the Supreme Court of the United States submitted November 10, 2025, awaiting a docket number. This paper is unique, groundbreaking, explains the root cause of civil breakdown in the United States for all issues, and is a threat to the establishment. One simple fix noted in this paper can solve most of the issues tearing America apart. I have been blackballed by the Brownstone Institute and Epoch Times, suppressed on X, and partially defunded by Substack, when they removed 10% of my voluntary paid subscribers in one day. I don’t have the time to solicit journals to publish this paper. However, if any journals or institutes wish to contact me to republish this, please feel free to contact me. AbstractBackgroundIn the past few decades, with increasingly greater frequency, attorneys and plaintiffs complain about procedural decisions in the courts. John Beaudoin, Sr., author of this paper, experienced three case dismissals in 2020, 2023, and 2023. Beaudoin then polled litigators of various ages in order to gain a stratified view of litigation process changes over the past fifty (50) years of the their collective experiences. Of the seasoned litigators polled, all agreed that the workload balance between procedural and substantive arguments in cases shifted in the past twenty (20) years from greater work-time in substance to greater work-time in procedure. This paper endeavors to empirically prove this hypothesis rather than rely on the memories and beliefs of elder litigators.Greater importance lies in whether justice is thwarted and the right to access the courts is violated when procedure dominates the court system and relegates substantive dispute resolution to the streets. Closing commentary offers reflections on the downstream consequences of a system awry from its mission of dispute resolution. Question PresentedIs it possible to empirically prove that meritorious cases and controversies are habitually dismissed by U.S. courts effectuated through heightened rules of procedure and evidence? If proven to a reasonable degree, how did this happen and what can be done to fix it? MethodsA review (1995-2024) of the number of civil complaints filed in United States District Courts by year and a review (1776-2024) of the number of citations of the most cited cases in U.S. history were performed using United States Government¹ data, Google Scholar² data, and Thomson Reuters’ Westlaw³ service data. ResultsExcess U.S. District Court civil cases filed in 2020 totaled 470,581, which is a 17.5 sigma event compared against excesses from a 25-year span 1995 through 2019, inclusive. The excess 2020 caseload calculated by trend method over the same span of years totals 180,538, or 62.2% more than expected. The greatest numbers of case citations in the history of the Untied States, by a large margin, are the two cases that redefined the civil litigation pleading standard to a heightened “plausibility” requirement, Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly (2007) and Ashcroft v. Iqbal (2009) (hereinafter known as Twiqbal). These two cases are each responsible for more dismissals in the past twenty (20) years than any other case in the more than two hundred (200) years of U.S. existence. Westlaw reports 391,246 and 372,011 case citations for each of the pair, respectively. ConclusionsThe management systems analysis of the United States Courts concludes that the Pareto efficiency of the court system has become tuned to habitual procedural dismissals rather than justice, fairness, and equity. The empirical results herein are irrefutable. A stark change occurred in the judicial branch almost twenty (20) years ago and is manifesting civil strife, riots, division, and increased tension among factions. One merely needs to review doctrinal case dismissals involving election integrity, climate change, illegal border crossings, transgenderism, child pornography and trafficking, Covid mandates, vaccines, and other social issues to see the consequences of unresolved disputes. When meritorious cases are refused by the courts, the disputes fester until they inevitably end up being decided in the streets. A simple solution to adjust the court system’s operations back toward its primary mission of dispute resolution is to employ balancing tests broadly to the rules of evidence and civil procedure. These balancing tests will protect the foundational rights of The People to due process and to access the courts for cases and controversies, id est, dispute resolution. Plain Language SummaryThe People are held together as a civil society through access to the courts for dispute resolution, effected through the U.S. Constitution Article III Section 2, known as the “cases and controversies” clause. The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) functionally manages the lower courts through their decisions in cases selected to be heard by SCOTUS. The District Courts broadly interpret the pleading standards manifest in Twiqbal to be significantly heightened, resulting in dismissals of meritorious claims. The habits formed in dismissing cases based on pleading standards spilled over to dismissing a greater number of cases via standing, summary judgment, qualified immunity, mootness, ripeness, and other dismissal doctrines. The 62.2% extra caseload in 2020 accelerated the habitual dismissals. The case citation rates of Twiqbal, nearly ten (10) times greater than the seminal case used in standing doctrine, Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife (1992), are strong evidence that habitual dismissal acceleration was caused by interpretations of the Twiqbal decisions. The data shows that this same pattern of doctrinal dismissal acceleration occurred a couple decades earlier for summary judgment standards based on Anderson v. Liberty Lobby (1986) and Celotex v. Catrett (1986). In summary, 2020 brought such a stark increase in caseload that it was impossible for the court system to hear all the meritorious cases. For survival, during the overwhelming workload event, courts heightened the pleading threshold for plaintiffs to have a case heard. Dismissals under Twiqbal became increasingly habitual, and the habit became part of the systemic organizational behavior of the U.S. Court system in 2020 and thereafter. Years 2021 and 2023 also brought significant excess caseload thus solidifying the accelerated, systemic, and previously formed habit of pleading stage dismissal of meritorious cases. Some of the organizational behavior habit formation models explored in this paper match the events of 2020 including the overwhelming workload event. IntroductionThe Covid era (2020 and thereafter) brought the greatest annual increase in civil litigation cases filed in the United States by a margin ten times (10X) greater than any other year in the prior quarter century. The dire excess of U.S. District Court cases filed in 2020 could not be efficiently processed by the system as it existed in early 2020. The only theoretical way the system could handle the extra workload in 2020 is if the staff was shirking an aggregate of 37.8% of every day and every year before the Covid era. Even if the staff had been working that inefficiently prior to 2020, other resources such as time cannot be made to accelerate in an instant of need. Thus, an assumption of this paper is that the court system, as comprised in 2020, could not efficiently process the extra 62.2% workload in 2020, especially because the greatest workload increase over expected annual totals in the preceding quarter century was only 5.7% in 1997. The systemic needs each year were determinable and forecastable based on relatively low variance in years (1995-2019), a quarter century, preceding 2020. To date, this is the most comprehensive methodological review of the incidence rates of U.S. civil cases filed by year and total SCOTUS case citation rates by case known to have been performed. Hopefully, similar and more detailed studies of the management system efficiency of the courts, and how it affects adjudication fairness and equity, will follow this paper. This study is intended to raise awareness of a systemic issue, so significant and dire, that it may lead to the fracture of the constitution (small “c”) of the United States. The subject matter of this paper has gone unmentioned and unnoticed by U.S. politicians, citizens, and media. The official data proves beyond reasonable doubt that there was a stark and untenable caseload increase in 2020. This management analysis and proposed solution are offered for the managing body, SCOTUS, to consider. Inaction on this issue will surely lead to continued devolution of American society toward incivility, first in social media, then in the streets. MethodsData SourcesWhile the case citation totals are disparate between Google and Westlaw services, likely due to counting criteria differences that each service employs, both Google and Westlaw demonstrate a relatively striking increased number of citations involving dismissal doctrines, especially summary judgment and pleading plausibility. Id est, under ceteris paribus, both services show the same patterns of excess summary judgment and pleading plausibility citations across all cases, though the numbers are different when comparing a given case across services. The U.S. Courts government website is assumed to be accurate in number of cases filed. Study SelectionIn order to determine excess caseload, data was extracted from United States Courts government website entitled, “Caseload Statistics Data Tables,” specifically, “Table C-8. U.S. District Courts–Civil Cases Filed, by Origin, Fiscal Year Periods Ending September 30.”[See 1] The Covid era (2020-2024) is selected as the period under test. For robustness and statistical significance, the quarter century preceding the Covid era was selected as the base against which to compare the period under test. In order to determine if there were functional changes in the court system that shifted from hearing cases on a substantive basis to dismissing cases via procedural hurdles, the most cited cases in the history of the United States were compared by quantity, by year they occurred, and by the holding thesis or subject matter for which the case is oft used as a basis of citation. Artificial Intelligence (AI) programs and web search engines were used to discover the cases deemed to be the most cited in the history of the United States for the purposes of this paper. The subject matter of each case was determined from the holdings. Thirty-two (32) cases were selected. These are not necessarily the top thirty-two (32) overall. Some were added because they were the highest in their “holding” category. For example, “personal jurisdiction” and “qualified immunity” were added. While some may argue that popular cases are missing or should be added, that does not excuse the fact that there is no explanation for the stark changes in 1986 for summary judgment and in 2007 and 2009 for the heightened pleading standard of plausibility. Data Extraction and VisualizationData was extracted through manual recording of web page searches performed on the U.S. Courts website [See 1], Google Scholar [See 2] case searches, and Westlaw [See 3] case searches. Due to the possibility of manual transcription error, all data entries were triple checked. Effective visualization is achieved through simple bar charts. A table is added for those who wish to verify the data or produce their preferred visualizations. Mathematical Methods and Statistical AnalysesFor case citation rates, there are four graphs offered. The first two are the raw totals of citations from Google and Westlaw. The next two graphs are the total number of citations for a case divided by the number of years since the case’s SCOTUS decision was issued. For U.S. District Court caseload by year, results are depicted in graphs: 1) raw caseload data, 2) excess caseload, 3) excess caseload as percentage, and 4) Z-Score of excess caseload. Determining Excess Caseload by TrendExcess caseload = Actual caseload - Expected caseload Actual caseload is gleaned from source data. Expected caseload is derived by approximating a line among Actual Caseload datapoints for base years 1995-2019. The line is then extended into Covid era years under test to get the expected values for each of years 2020 through 2024, inclusive. Excess caseload percentage = Excess caseload ÷ Expected caseload The linear least squares approximation model to approximate such a line is found within spreadsheet macros SLOPE and INTERCEPT. Expected deaths = mx + b where, m = slope, and b = intercept Spreadsheet equations are as follows: m “= SLOPE({1995value, 1996value, 1997value … 2019value}, {0,1,2 … 24})” b “= INTERCEPT({1995value, 1996value, 1997value … 2019value}, {0,1,2 … 24})” From the slope and intercept constants, the following formulae yield the expected values for each year.

The formula used by the Numbers™ spreadsheet program for SLOPE function is: m = (nΣ(xiyi) - ΣxiΣyi) ÷ (nΣ(xi2) - (Σxi)2) The formula used by the Numbers™ spreadsheet program for INTERCEPT function is: b = (Σyi - mΣxi) ÷ n Where, in this study:

Determining Z-Score of Excess Caseload

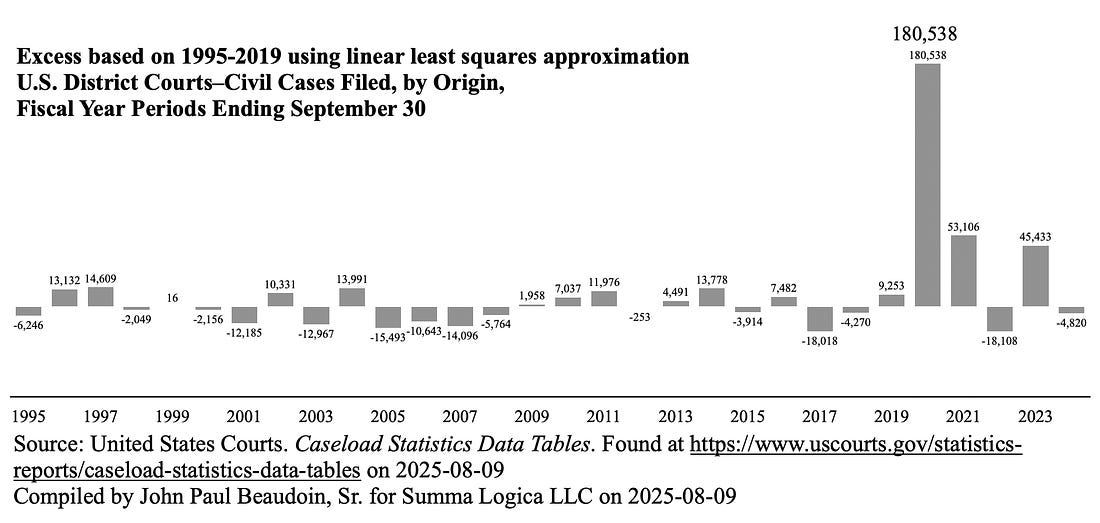

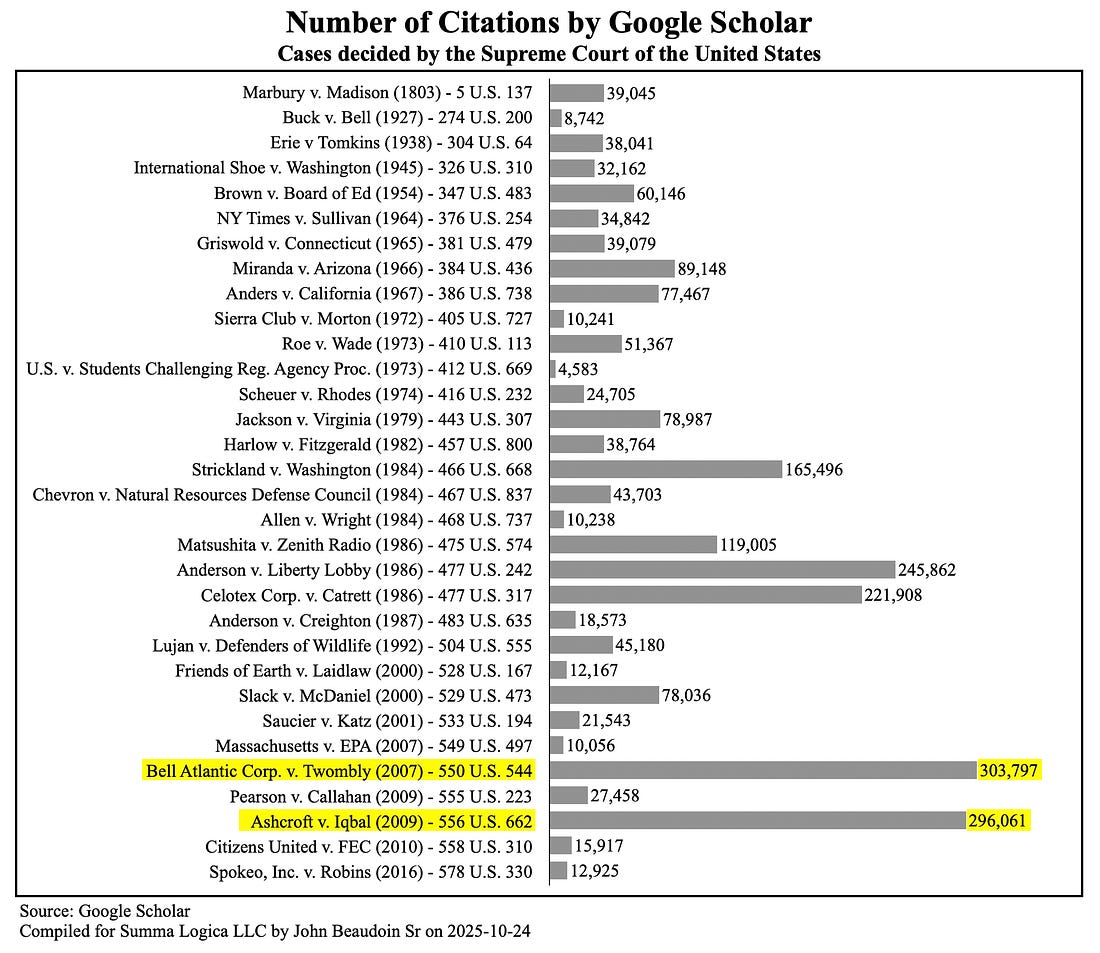

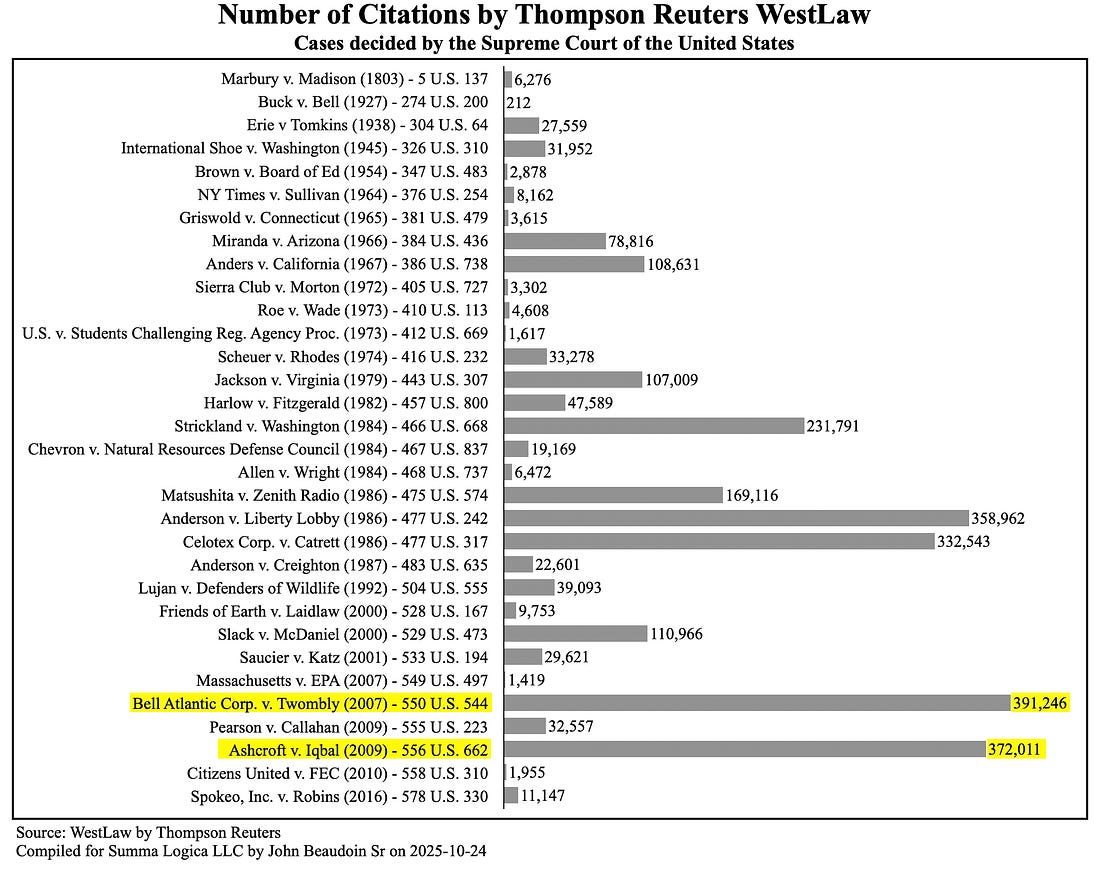

µ = (∑ai) ÷ n σ = √ ((∑(ai - μ)2 ÷ (n - 1))) Zi = (ai - µ) ÷ σ ResultsExcess 2020 Cases FiledNormal Method - Using the conventional normal distribution probability method and base years 1995 to 2019, the caseload mean is 271,603, standard deviation is 14,663, and 95% confidence interval [95% CI] is 265,550 to 277,656. Raw data totals by year are offered in Figure 1. Year 2020 is an overwhelming workload event. Figure 1Trend Method - Using linear trend method and base years 1995 through 2019, inclusive, excess civil cases filed in 2020 total 180,538 as seen in Figure 2. Figure 2Figure 3 depicts excess percentage by year calculated against base years 1995 to 2019. The range is (6.3%) in year 2017 to 5.7% in year 1997. Year 2020 depicts 62.2% excess over expected, or more than ten times (10X) the greatest increase in the prior twenty-five (25) years. Figure 3Year 2020 yields the astounding Z-Score of Excess cases filed to be 17.53 as seen in Figure 4. Figure 4Table 1 is offered as the basis for Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4. Table 1Number of Case Citations by CaseFigures 5 & 6 depict the number of citations for each of thirty-two (32) of the most cited cases in U.S. history, ordered by year, earliest at top to most recent at bottom, for data gleaned from Google Scholar “Cases” and Westlaw by Thomson Reuters, respectively. Figure 5Figure 6Notable factors in Figures 5 & 6 are discussed later in the analysis section. The sheer numbers depict the reign of Twiqbal in the U.S. history of case citations; and this reign only took seventeen (17) and nineteen (19) years. The Twiqbal pair is used almost exclusively to dismiss cases based on the heightened pleading standard, where the defense purports that there are not enough facts on the complaint to show that the plaintiff is entitled to relief. On the heels of Twiqbal are the two (2) cases used to accelerate the use of dismissals via summary judgment. Adding the context of time, case citation rate (citations per year) is depicted in Figures 7 & 8 in which the number of citations for each case is divided by the number of years since SCOTUS issued its decision. Figure 7Figure 8Ceteris paribus means “other things in parity” or “all other things being equal” as is commonly stated. In this context, view each of Figures 7 & 8 separately. Both services, Google and Westlaw, depict the same relative differences under ceteris paribus. The actual totals for each case from service to service differ substantially, but that is likely due to the counting criteria employed by each service. The case citation rates of the Twiqbal pair are disparately, irrefutably, and anomalously greater than all others. Another Latin turn of phrase applies, res ipsa loquitur, “the thing speaks for itself.” The evidence of both the 2020 caseload increase and the Twiqbal case citation rates is so stark that the Question Presented is answered affirmatively and beyond reasonable doubt. How the issue came to exist and what can be done to mitigate the damage to society is discussed next. DiscussionIssue-in-Fact: Overwhelming workload eventThe greatest excess in caseload over a 25-year span (1995-2019) was 5.7% in 1997. The year 2020 excess was 62.2%, which could not have been predicted. Statistical results yield that 2020 excess is 17.5 standard deviations above the 25-year mean. The likelihood of that event occurring would be effectively zero The U.S. District Courts were not prepared for such an overwhelming workload event. They did not add 62.2% more staff, computers, office real estate and other incidentals for civil cases. And the staff did not all work 62.2% more hours every workday for a year (13-hour days compared to 8-hour days). Issue-in-Fact: Exponential increase in dismissal doctrine citationsThe case citation rates of the Twiqbal pair are roughly an order of magnitude more than most other seminal cases in the history of the United States. The only other pair that is close at fewer than half the Twiqbal rates are Anderson v. Liberty Lobby (1986) and Celotex Corp. v. Catrett (1986), used in cases involved in summary judgment motions. Management Analysis IntroductionSCOTUS manages the function of the lower courts via decisions in cases. This is apparent by the Twiqbal pair citation rate. Twiqbal heightened the pleading standard to a “plausibility” requirement. Under Twiqbal, defense attorneys submit motions to dismiss rising under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (Fed. R. Civ. P.) 12(b)(6) “Failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.” These motions to dismiss usually cite at least one case of the Twiqbal pair stating that not enough facts were pled in the complaint (lawsuit) per the Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(a) requirement that the complaint be a “short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief.” SCOTUS’ decisions in Twiqbal caused (managed) the behavior that resulted in the citation rates depicted in Figures 5, 6, 7 & 8. Management Analysis of Organizational Behavior - Habit formationAs the functional managers of the lower courts, SCOTUS is responsible for the consequences of Twiqbal and other cases. Models of habit formation in organizations are well-established in management research and academia.

Ecological Systems Theory explains the reaction that likely occurred throughout the entire U.S. District Court system in 2020. Having no other means to process the overwhelming workload event, meritorious cases were dismissed as the court system staff adapted to survive. 180,538 excess civil cases were filed in 2020. There is no plausible explanation for how the excess was handled except dismissals en masse. The habit of dismissal, which, according to attorneys polled over the past five (5) years, was already an issue in the U.S. District Court system since Twiqbal. The case citation rates of Twiqbal are significant factual evidence of habit formation effectuating dismissals of meritorious cases. Review of subsequent years shows that 2021, the year of Covid vaccine mandates, and 2023 also manifested significant increases in caseloads, thereby perpetuating and perhaps accelerating habitual doctrinal dismissals. Further research and systems analysis are required to prove these attorney opinion statements. Despite the lack of data for the number of citations each year for each case, it is important to contemplate them herein in the hope that behavioral economists and systems analysts will continue this nationally important court systems analysis. In 1986, summary judgment seems to have become habitually employed as indicated by case rates of Anderson v. Liberty Lobby and Celotex Corp. v. Catrett. It is now ubiquitously known throughout the litigation industry that trial judges in state and U.S. district courts prefer not to have trials. Judges openly state that they prefer cases settle through negotiation or mediation rather than trial. And if cases do not settle, then judges often allow summary judgment to dispose of cases, otherwise bound for trial, in the discovery phase of litigation. The logical next step, if courts wish to avoid trials, is to dismiss them before discovery. This is when motions to dismiss for “failure to state a claim,” standing, qualified immunity, sovereign immunity, mootness, and ripeness are submitted and often granted. Meritorious cases are dismissed based on subjective decisions of the court, many of which should be left to a jury. Management Analysis - Authority for dismissal doctrinesThe U.S. District Courts derive authority from Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which formed the federal courts. Courts refer to one’s “Article III standing” rights, when discussing standing doctrine. Article III does not mention standing expressly and implies standing only in the context of requiring that the dispute involve a federal law or the parties be in diversity (be from different states). From that abstract implication began a long, winding, and slippery slope of statutory and case law that created an intricate web of doctrinal tests used to dismiss cases at various stages of litigation. In 1986, the standard for summary judgment was heightened. In 1992, the standard for “standing,” was heightened. Almost 20 years ago (2007 & 2009), the “pleading” standard was also heightened. The authority for courts to make their own rules of evidence and rules of civil procedure and criminal procedure is derived from 28 U.S. Code § 2072 “Rules of procedure and evidence; power to prescribe.” Under Fed. R. Civ. P., motions to dismiss are constructed for standing, pleading insufficiencies, summary judgment and other dismissal doctrines. For example, the authority to dismiss under Twiqbal follows the path from the U.S. Const. Art. III § 2 to 28 U.S. Code § 2072 to Rule 8 to Rule 12 to the Twombly and Iqbal decisions. At each juncture from complaint to trial, motions are submitted by defendants to dispose of the case. The court must decide whether to deny or allow the motions, id est, whether to dismiss the case. The standards to have a case heard have been heightened at each stage making it nearly impossible to have even a meritorious case heard in U.S. Courts, according to most elder statesmen attorneys surveyed, and supported by the statistics in this paper. Every time a case is dismissed before trial, the court is stating that the case has no merit and that the time and resources of the court should not be wasted on the case. Given that the mission of the courts is dispute resolution, what are the risks of habitual dismissal based upon heightened standards of pleading, standing, evidence et al? On the other side of dismissal doctrines are the rights of the plaintiffs. While dismissals purport to protect defendants and the courts from the costs of frivolous litigation, the rights of the plaintiffs seem to have been subjugated in context. The chain of legal authority for dismissal doctrines to effectuate tests, such as plausibility of facts in a complaint, is quite attenuated. Measure that attenuated legal authority of abstract prose in the Twiqbal standard against the multiplicity of legal authority including the Article III right to access the U.S. Courts for cases and controversies, First Amendment right to petition the Government for a redress of grievances, Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial for suits at law, and Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and equal protections of the law. These foundational rights that hold civil society together are subjugated and cast aside by attenuated authority of abstract stare decisis when a meritorious case is dismissed on procedure. This paper does not argue that procedural rules are not necessary for the proper order and economic efficiency of operations within the courts. There obviously needs to be a set of rules. However, without proper checks and balances on those rules, the system chokes the rights of The People to have their disputes heard and resolved in a proper and civil manner. Management Analysis - At-Law v. In-EquityLaw versus equity is important for the reader to understand. The United States inherited the English system of law, or legal matters. Both nations had separate courts for matters at law and matters in equity. In matters at law, judges must follow the law, whether statutory law or stare decisis (case law). For all other matters in which there may not be an express statute or congruous case law on point, a judge sits in equity, or chancery, and makes decisions based on fairness and equity. Both England and the United States merged the separate law and equity courts more than a century ago. In doing so, the same court and judge adjudicates matters at law and in equity, even in the same case. Even after merging the courts, the United States had a separate “Federal Equity Rules” for procedure until the Rules Enabling Act of 1934, now updated as 28 U.S. Code § 2072. The Rules Enabling Act provided authority to the courts to create the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which merged the rules of procedure for matters at law and matters in equity; and also enabled rules of evidence and criminal procedure. In matters in equity, the court employs tests, two of which are a balance of harms, or balance of equities, test and a test of the effect of a decision on “the public interest.” The balance of harms analysis is to ensure that a decision favorable for the complainant will not inequitably bring greater harm to the defendant, id est, greater harm when balanced against the remedy sought by the complainant. Regarding the public interest, the court seeks to ensure that a favorable decision for the complainant will not adversely affect the citizenry. For example, if a canon needs to be put on the land of the complainant for a week in order to repel an invasion, and without which one million citizens will die, the court will weigh the public interest of placing the canon against the individual liberty and property interest of the complainant. Interestingly, when a complainant sues the government for a policy, or a false representation by government that caused a private party to create such a policy, and that policy violates a right of the complainant, the government purports to represent the public interest. In other words, in a case of suing a government over a policy, the balance of harms and public interest tests merge into a single test, which invariably pits individual liberty versus the public interest. And the courts very often favor government. This paper asserts that most of the rules of civil procedure now in effect in the U.S. Courts are matters in equity. The courts should decide procedural matters in the unique and individual context of the cases, including the facts pled. Attorneys and courts attempt to view civil procedure through a lens of “at law” rather than “in equity,” which omits the balance of harms and public interest tests. For example, the pleading standard of Lujan for standing doctrine is viewed as a matter at law. Yet all three prongs of the Lujan standing test are somewhat abstract prose, requiring objective fairness in context of the case, thus framing it as a matter in equity and fairness, not a matter at law. Balance of harms and public interest tests should be employed in procedural decisions. Instead, courts use attenuated authority of standing doctrine, subjugate foundational rights of due process and access to courts for dispute resolution, and dismiss meritorious cases. Management Analysis - Judicial Economy Macro- and Micro-At a macro-economic level, the courts argue that they had to dismiss meritorious cases based on judicial economy because the court system could not handle such an overwhelming workload event in 2020. At a micro-economic level, the courts argue that, for each case, they weigh the economic harm to a defendant and to the court versus the frivolity level of the claim brought by the plaintiff or petitioner. Neither of these arguments is based on facts and systems analysis. The courts do not seem to assign the appropriate weight to the harm done to plaintiffs in dismissals. In the macro-economic view of 2020, it is likely that most of the 180,538 excess cases could have been avoided by hearing and adjudicating the first excess cases as they were filed. The issues of 2020 were numerous, but most centered around Covid. Beaudoin filed a case in 2020 (Beaudoin v. Baker, 530 F. Supp. 3d 169 (D. Mass. 2021)) regarding the face mask mandate in Massachusetts. He claimed that it violated his First Amendment right to receive speech from others as he is partially deaf and needs to see people’s lips in order to hear better. Governor Baker changed the order for the entire state to get around the legal theory pled by Beaudoin. As a result, the state submitted a motion to dismiss for lack of standing shortly after the face mask order was changed. The court dismissed the case because the injury particular to Beaudoin was resolved. If his case (Beaudoin v. Baker, 2020) had proceeded through trial, including facts and substantive arguments, several face mask cases would not have been filed in 2021 in Massachusetts against the mandate to mask school children. If cases involving Covid testing, business closures, and social distancing were heard and resolved in early 2020, then years of subsequent excess cases would not have been filed. The U.S. elections of 2020 brought another wave of cases that could have been avoided had only one or a few been substantively adjudicated. Instead, nearly all were dismissed using dismissal doctrines without The People having the benefit of observing facts, evidence, and meritorious arguments at trial. As a result, societal schisms, incivility and factional entrenchment increased. There is no way to tell how many of the 180,538 cases could have been avoided in 2020, but it surely would be most, if not nearly all of them. In other words, dismissals of cases in 2020, for purported reasons of judicial economy, actually caused more cases to be brought because legal issues festered in society without resolution. A robust analysis would likely show that judicial economy fails as an excuse at the macro-economic level. In the micro-economic analysis, examine any given case using facts and estimated trial time. Beaudoin’s mask case (Beaudoin v. Baker, 2020) would have taken fewer than 30 days of discovery and one to two days of trial. Discovery would have been a few hours work for each side. Instead, the actual case docket contained the original complaint, multiple motions to enlarge time, motion to dismiss, amended complaint, motion to dismiss, opposition memorandum, and multiple notices of appearance and supplemental authority. Tens of hours of extra work, docket entries, and 9 months of time were expended. Compare to the alternative of 30 days of discovery and 2 days of trial had the case not been dismissed via the civil procedure technicality gauntlet. The current system, for purported reasons of judicial economy, fosters bureaucratic inefficiency, negatively exacerbating the judicial economy issue. Procedure dominates at the expense of justice and equity. Beaudoin’s second federal case against the Governor et al, for violation of his rights regarding the Covid vaccine, is another example of inefficiency of judicial economy due to habitual dismissal doctrine overuse. The consequences of doctrinal dismissal are significant in this example. Numerous docket filings for more than a year resulted in this meritorious case being doctrinally dismissed on both standing and failure to state a claim, with Lujan and Twombly cited in the order dismissing the case. Add to that the notice of appeal, appellate brief, and another 1.5 years to the appellate decision affirming. Add also the cycle time and expense of the Petition for Writ of Certiorari filed in the Supreme Court concomitantly with the publication of this paper. Time and effort from the District Court, the First Circuit Court of Appeals, and SCOTUS could have been averted by hearing this case more than three (3) years ago when it was served. It would have only taken two (2) or three (3) months to be completely disposed in 2022. Counterarguments to the economic analyses herein elucidated do not hold up against the facts in this Management Systems Analysis. Judicial economy, when performed by economists, behavioral economists, and systems analysts will not side with the courts in their propensity to dismiss cases, especially during overwhelming workload events. The solution is to hear the cases, solve the legal issues, and avert multiple cases from being subsequently filed. Conclusions and Proposed SolutionThe data strongly suggests that about forty (~40) years ago, dismissals for summary judgment became habitual, rising under Anderson v. Liberty Lobby and Celotex Corp. v. Catrett. The data proves beyond reasonable doubt that fewer than twenty (<20) years ago, pleading insufficiency dismissals became habitual rising under Twiqbal to an extent never before seen in U.S. Court operations. The U.S. Courts were met with an overwhelming workload event in 2020 causing a res ipsa loquitur conclusion that meritorious cases were doctrinally dismissed en masse since March of 2020. The rights to dispute resolution, due process, and trials for lawsuits are foundational for American society to remain civil. These foundational rights are subjugated by an attenuated legal authority for rules of procedure and evidence. In fact, the Rules Enabling Act 28 U.S. Code § 2072(b) states, “Such rules shall not abridge, enlarge, or modify any substantive right.” Yet these abridgments via habitual doctrinal dismissals now happen as a matter of custom and practice in the U.S. Court system. Some of the procedural abuses and violations of foundational rights include 1) over-consolidation of cases for judicial economy where class certification would fail, thus depriving each case of its individual merit, 2) dismissal of cases for ripeness, where the plaintiff must wait to be injured before petitioning the courts, 3) dismissals for mootness, sometimes multiple times between the same parties where the defendant continually deploys and rescinds a policy or mandate to achieve continual dismissals on mootness (See Health Freedom Def. Fund, Inc. v. Carvalho (9th Cir. 2025)), 4) dismissals under Twiqbal as courts refuse to earnestly review facts pled in the complaint against a government defendant, 5) protective orders allowed based on highly speculative danger from social media posts, thus depriving plaintiffs of due process in discovery, and 6) dismissals for summary judgment in which courts overstep their authority into the realm of the jury as deciders of fact. Nearly all procedural and evidence decisions by the courts are effectively equitable decisions, id est, judge-only decisions based on the nuanced sets of facts and circumstances for which generalized statutes and stare decisis are not fit for purpose. Once recognized as equitable, SCOTUS need only compel the application of balance of harms and public interest tests to the rules of procedure and evidence, especially noting that decisions to dismiss, protect, or otherwise confound litigants must be weighed against the litigants’ Constitutional rights. This concept is not new to the Courts. Are not “rational basis” and “strict scrutiny” tests nothing more than equitable tests that balance individual liberty versus the public interest? Last WordThe thesis is proven. The U.S. Court system refuses meritorious cases en masse; and if not soon corrected, the United States society and nation are in peril of mortal fracture. Equity tests, adding proper weight to individual rights, in matters of procedure and evidence, would be incremental, not radical, change. Such a solution is simple, elegant, and has a high likelihood of success to mend the broken U.S. Court system. References1 (2025). United States Courts. Judicial Business 2024. Caseload Highlights. U.S. District Courts. Civil Filings. Found here https://www.uscourts.gov/data-news/reports/statistical-reports/judicial-business-united-states-courts/judicial-business-2024 on 2025 October 26. 2 (2025). Google Scholar. Google. Found at https://scholar.google.com/ 3 (2025). Westlaw. Legal Research Tools. Thomson Reuters. Found at https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/westlaw 4 Duhigg, Charles. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House. 5 Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 6 Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology. 7 Bandura, Albert. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Pentice Hall. 8 Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. Macmillan. 9 Bronfenbrenner, Urie. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press. Case AuthoritiesAnderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986) Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317 (1986) Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992) Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007) Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662 (2009) Twiqbal (portmanteau of Twombly and Iqbal) Health Freedom Def. Fund, Inc. v. Carvalho, No. 22-55908, 2025 WL [TBD; slip op.], (9th Cir. July 31, 2025) (en banc), aff’g in part & rev’g in part 104 F.4th 715 (9th Cir. 2024), reh’g en banc granted, 127 F.4th 750 (9th Cir. 2025). You're currently a free subscriber to The Real CdC’s Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

No comments:

Post a Comment