I feel one of the biggest issues in modern medicine is that it’s become so disconnected that patients often can’t form a meaningful therapeutic relationship with their physician. Because of this, my goal here was always to be able to correspond with everyone who reached out to me (e.g., through comments). Unfortunately, due to the size of this publication, that’s no longer possible. To address this, I’ve done monthly open threads where I cover a brief topic and then provide an open forum for any questions readers wish to ask me about . In this month’s open thread, I wanted to discuss a fairly under-appreciated aspect of health—how your clothing can affect your health for the better or worse. Note: over the last few weeks I’ve had to switch from two articles a week to one. This is because I have been trying to complete a synthesis of all the existing DMSO literature as quickly as possible and after starting that three months ago, I gradually realized there was much more to go through than I initially anticipated. That said, I am now quite close to finishing it and looking forward to returning to the normal schedule and the other topics I’ve been waiting to cover! A Chance Plane RideYears ago, a friend of mine was seated on a plane next to a chief executive of a major American chemical company that was notorious for polluting the environment and sickening large numbers of Americans with its products. After building up a friendly rapport, my friend asked the executive what he considered to be the most important piece of advice he had to share. The executive immediately responded:

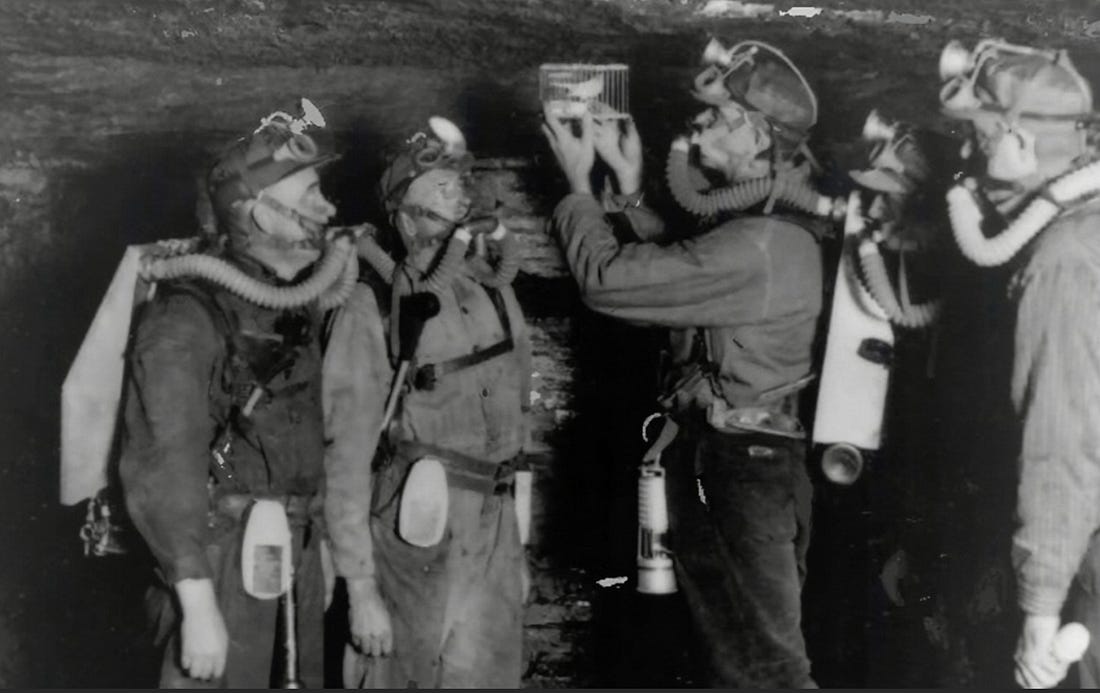

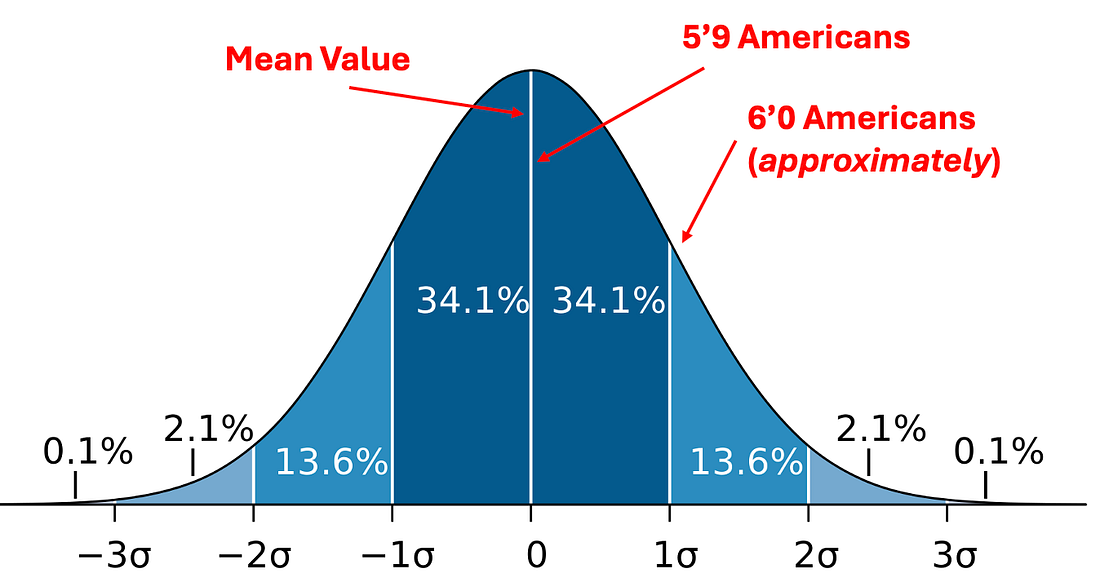

I’ve never forgotten that story, and over time my patients have helped me to appreciate just how many nasty chemicals end up on our clothing that most of us never notice.Canaries in the Coal MineBirds tend to be much more sensitive to environmental toxins than humans (e.g., I’ve heard numerous stories of birds dying while in the vicinity of someone cooking with a teflon pan). This principle in turn was utilized by coal miners who were always at risk of a lethal toxic gas buildup (particularly of carbon monoxide) occurring in the mines. Since carbon monoxide is odorless, they would bring canaries with them and if the canaries suddenly died, they immediately got out as they knew they eventually would too. One of the fundamental principles in statistics is that variable phenomena tend to follow a bell curve distribution, with the average value (e.g., adult American men being 5’9—which is a bit above the global average) being by far the most common, while values become exponentially rarer as they move further away from that mean (e.g., only 15% of adult American men are at least six feet tall). Sensitivity to pharmaceuticals and environmental toxins (e.g., synthetic chemicals) follows a similar pattern, with there being a minority within the population that is extremely sensitive to these things (and conversely, on the end of the bell curve, another minority exists on the opposite end which has a very high tolerance to them). I’ve always felt genuinely bad for the sensitive people as the medical system frequently dismisses their symptoms (as the majority of patients do not share their sensitivities) and they are often left alone to struggle with a variety of things most people can’t relate to let alone empathize with. Note: I’ve tried to use this Substack to bring attention to their situation (e.g., this article discusses the unique sensitivities patients in this constitutional archetype experience, this article explains the frequent association between ligamentous laxity and pharmaceutical injuries along with how things like manganese can be used to treat hypermobility and this article reviews the dysfunctional mitochondrial danger response many of them are stuck in). For additional context, I consider myself a “somewhat environmentally sensitive” individual, but I have been close to numerous “highly sensitive” individuals and witnessed what they go through each day firsthand. One

of the major challenges with all of the environmental toxins we are

exposed to is determining how much our exposures to each of them

actually matters, as there are so many of them it borders on impossible

to identify which ones are actually directly responsible for the chronic

illness an individual experiences. That said, a few individuals like Joseph Pizzorno

have done a remarkable job of quantifying the evidence that

demonstrates the harms these toxins have created, and in clinical

practice, we periodically see a complex and debilitating illness resolve

once a comprehensive detoxification protocol is administered which

addresses toxin exposures that occurred years if not decades ago. The highly sensitive individuals frequently refer to themselves as “canaries” under the logic that the same environmental toxins they experience severe reactions to are also affecting everyone else on a more subtle and insidious way (e.g., by giving them cancer ten years down the road). I’ve taken this point to heart, and both used them as an early warning sign something is dangerous and a guidepost for all the things in the environment I should be avoiding, under the logic that if I mostly avoid all the things the canaries are sensitive to, I probably won’t have any major health issues (which has so far held true). The

COVID vaccines in turn help to illustrate many of these concepts. For

instance, since they are a highly toxic agent, once they hit the market,

immediately I began to have numerous patients show up who had severe

reactions to them (which suggested their average injury value was very

high) and hence was not surprised as I began to hear more and more

stories of sudden death following their use, and later numerous

insidious chronic complications of the shots that onset in the years

after the injection. Clothing ToxicityOne of the frequent points I raise here is that our regulation of pharmaceuticals drugs is woefully inaccurate due to there being so much money in medicine there is inevitably enough to pay off a bureaucrat to approve and then often mandate dangerous and ineffective products (e.g., like remdesivir, all the data showed Paxlovid was useless but the government nonetheless spent billions giving it to America). However,

while the pharmaceutical regulatory situation is abysmal, it’s actually

much better than the cosmetic industry, as very few resources are

devoted towards ensuring those products are safe. In turn, I’ve lost

count of how many people I’ve met who discovered they reacted to

specific chemicals in their shampoo, makeup or soaps and were forced to

gradually shift to all natural products to get through life. I hence

avoid most of the products on the market and try to either make the ones

I use at home (as that way I can guarantee what’s in them) or buy very

specific brands we believe are clean. Sadly, while some regulation exists for cosmetics, almost none exists for fabrics or the chemicals put onto them (other than things like mattresses needing flame retardants—many of which are toxic). Because of this, we wear a lot of things we just should not be wearing. With clothing, because of how I react to synthetic fabrics like polyester (they just don’t feel good on me—for example when it’s hot and I sweat it often feels as though plastic fibers are coming into my skin), I’ve long suspected there are significant issues with the fabrics. Likewise, the tendency for feet to sweat is why I believe having socks made from a natural (and relatively dye free fabric) is fairly important. Note: one of the most intriguing models I’ve come across to explain why synthetic clothing causes issues arises from the fact that unlike natural fabrics, they generate positive ions around the wearer, which I believe is due to them removing negative charges from the surfaces they contact (which for reference is the mechanism behind static electricity). Excessive positive ions (or a lack of negative ions) in turn have been linked to a variety of health conditions, many of which I believe are reflective of them weakening the (negative) physiologic zeta potential in their immediate vicinity (e.g., most of the existing data demonstrating their adverse effects is in regards to the respiratory tract—which makes sense since positive ion exposure is typically through inhalation). In certain cases, the skin is also extremely responsive to changes to zeta potential (e.g., much of the data on negative ion therapy was gathered from burn units—a challenging condition known to be heavily influenced by blood sludging [which in turn results from impaired zeta potential]), so the positive ion from synthetic fabrics may account for some of the reactions these fabrics cause. Since a few of my colleagues have had similar experiences with clothing, we’ve made a point over the years to ask our highly sensitive patients how they respond to clothes and have found the following: •Quite

a few of them learn on their own that they need to wash new clothes

before wearing them. Furthermore, some find they need to wash them 3 or

so times before they can wear them without reacting to the clothing.

Additionally, they must almost always use a clean and fragrance free

detergent, and one of my own struggles is to make sure my clothes never

get cleaned in a toxic detergent because the smell will often linger

with the clothes for a long time. Finally, I completely avoid using

dryer sheets (although I find they are not as problematic as

detergents). •Many

of them find they cannot tolerate the labels on their clothes (e.g.,

the tag at the back of the neck of most T-shirts) contacting their skin

and have to cut it off. •Many of the reactions our sensitive patients exhibit resemble mast cell reactions. Additionally, I’ve also met numerous people who react to scented products others are wearing (e.g., colognes, body sprays, or perfume), but sadly the wearers rarely consider how that choice will affect their target audience. Note: many similar stories to this have been shared by readers. Clothing FittingWhile the fabrics you use matter, I presently believe how they fit to your body is more important as tightly fitting clothes (or rings) can restrict many important circulations through the body. In turn, we frequently notice sensitive patients with chronic illnesses will, of their own volition, choose to wear looser and looser clothes—something I believe is due to those patients frequently having an already impaired fluid circulation throughout their body (as complex illnesses often go hand in hand with an impaired zeta potential and as discussed here, easily compressible vessels such as those seen in hypermobile patients). I will now focus on four specific areas. CorsetsSomething most men have difficulty appreciating (let alone empathizing with) is how much pressure society (e.g., in America) places women under to conform to specific appearances that largely exist to fund the fashion industry. The worst of these offenders were the corsets, which to quote Wikipedia were:

As you might imagine, wearing that was not the best thing for one’s health:

While it seems absurd people would do that, we still have many vestiges of it today. For instance, women are often encouraged to compress their waist and breathe through their chest to attain the elusive hourglass figure (which is not healthy), and numerous breathing instructors have shared that one of the greatest challenges they’ve faced in teaching abdominal breathing (which is great for your health) is that the women they teach often have a great deal of difficulty doing something that goes against their conditioning to have a thin waist. Likewise, many less extreme corsets (e.g., the “waist trainers”) are commonly sold online because a lot of people buy them. BrasPresently, Americans spend roughly 20 billion dollars a year on bras, which is remarkable given that prior to a century ago (the 1910s to be precise), almost no one wore them (whereas now between 80-90% of women do). In turn, almost every woman assumes bras are something women have always worn and are not aware of the massive marketing campaign the fashion industry did to normalize this practice (which was essentially done as a pivot because they could no longer sell corsets to women). Since women never wore bras for most of human history, it raises a simple question—might there be any downsides to the practice? Presently, I believe a good case can be made for the following: Pain—bras

frequently cause chronic back or rib pain (which goes hand in hand with

restricted breathing) along with neck, shoulder and breast pain, and as

many women can attest, it feels so good to take your bra off. In turn,

whenever I have a patient who complains about pain in the region of her

back or rib that her bra digs into, I counsel them to consider removing

the bra. Breast Shape—one of the most controversial points on this subject is whether wearing a bra “worsens” the shape and quality of one’s breasts. Very limited evidence exists to support this contention (e.g., that it increases sagging over time), but the honest truth is that no one has ever wanted to formally study this in a large trial, so it’s technically “unproven.” That said, in my own observation (and that of others like this gynecologist) is that not wearing a bra is cosmetically beneficial to the breasts. I mention this because one of the most common marketing tropes for bras is that they help one maintain the breast’s youthful appearance—despite no evidence existing to substantiate that claim. Metal Allergies—One estimate found 17% of women are allergic to nickel (whereas 3% of men are) and hence suffer issues where it contacts the skin. This is frequently a problem for bras because their underwire is normally made from nickel (due to it being the cheapest material to use) and the nickel frequently coming in contact with the skin (due to sweat leaching it out and friction rubbing it against the skin). Remarkably, despite many women being sensitive to nickel bras, the industry has not been motivated to make nickel free ones be easily accessible to women (which is something I’ve always found extraordinary). Note: a variety of other products (e.g., buttons, glasses, and belts) also use nickel, so a potential nickel allergy is always something that should be considered when unusual symptoms start, particularly in a localized area. For those interested in learning more about nickel allergies, this article describes a lot of it from a patient’s perspective. Impaired

Circulation—since the bras compress the breast, it’s reasonable that

they might also impair their circulation and numerous anecdotal reports

support this. Likewise, this may explain some of the other issues

commonly associated with bras (e.g., headaches and indigestion).

However, in my opinion, the greatest issue is impaired lymphatic

drainage from the breasts (as lymphatic circulation is very sensitive to

being obstructed by an external pressure). Breast

Cancer—the most taboo subject with bras is their link to breast cancer,

and in turn, every major cancer organization attacks this contention,

insisting there is no evidence to support it. Conversely, an argument

can be made it is plausible since many holistic schools of medicine have

found cancers are linked to lymphatic stagnation and the most common

site of breast cancer (the upper outer quadrant which lies before the

armpits) is also a primary lymphatic drainage site for the breasts. Furthermore, there are some conventional sources that support this assertion (e.g., this article

highlights how many skin cancers are associated with regions of

lymphatic stasis and cites evidence indicating that is a product of

lymphatic stasis creating immune stasis that promotes tumor growth and this article also ties cancer to lymphatic disruption). Likewise, there is some acknowledgment within mainstream sources that bras create lymphatic stasis which can give rise to breast cysts. In turn, there is some evidence to support the contention bras are linked to breast cancer. Specifically:

This for reference is 4-8 stronger than the association between smoking and lung cancer and is discussed further in the book Dressed To Kill: The Link Between Breast Cancer and Bras. •A 2009 Chinese study found that avoiding sleeping in a bra lowered the risk of breast cancer by 60%. •A 2012 Chinese study of 400 women found sleeping with a bra made women 1.9 times more likely to develop breast cancer. •2016 Brazilian study of 304 women found women who were frequent bra wearers were 2.27 times more likely to have breast cancer. •A 2019 Iranian study of 360 women found women with breast cancer on average wore bras longer than women without, with the greatest difference being observed in how much it was worn when they slept. The increased risks of breast cancer seen here were smaller than those in the other studies but still were statistically significant. •Conversely, there is also one 2014 study (produced by researchers at a major cancer center that takes in a lot of corporate money to bring new cancer pharmaceuticals to market)

which refutes the link between bras and breast cancer. This study is

repeatedly cited by establishment cancer organizations to debunk the

link between the two, and in many cases, those organizations also

falsely claim it is the only scientific

study that ever evaluated the link between bras and breast cancer.

Critics of this study, in turn, suspect it’s negative finding were in

part due to it only evaluating post menopausal women whereas the

previous studies found the association in premenopausal women. In turn, my feelings on this subject are as follows: Social pressures frequently make it very challenging to go braless, and women who chose to do so need support. My hope is that being able to understand bras can be quite uncomfortable and unhealthy to wear can help create the empathy to support women making this choice. TiesEver

since I was young, neckties have never been something I could relate to

(e.g., one of my first memories of them was associating them with Mr. Snuffleupagus

from Sesame Street and thinking it was weird people would want to have

an elephant trunk hang off them). As I entered practice, I began to

notice I would periodically see patients who appeared to be developing

symptoms from the tie impeding blood flow in or out of their neck due to

it being tied too tightly. There is also some data to support my observations. For example: •A 2011 study

found neckties decreased cerebrovascular reactivity (the ability of

cerebral vessels to dilate or constrict in response to challenges or

maneuvers), which suggests it also impaired cerebral blood flow. Note: since ties often are colonized by bacteria, they are frequently cited as a potential vector for doctors transmitting infectious diseases to patients. Presently, it’s unclear if sufficient evidence exists to support that contention. PantsAnother unfortunate fashion trend is wearing tight pants. As I hope the above points show, this can be potentially problematic, and we periodically see patients who are suffering from pants that are just too tight. Some of the common issues with tight pants include: •Becoming twice as likely

to develop severe pain in the vulva region (termed vulvodynia), along

with other forms of irritation from the tight pants rubbing against the

area. Additionally, many believe tight pants can also cause microbial imbalances of the vagina (e.g., bacterial vaginosis). •A 2012 survey

of 2000 men wearing skinny jeans found 50% experienced groin

discomfort, more than 25% suffered bladder problems, and 1 in 5 men

experienced a twisted testicle. •Significant numbness, tingling, and pain (e.g., burning) in the outer lateral thigh due to tight pants compressing the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Note: there are a variety of other conditions tight jeans are thought to be linked to (e.g., acid reflux or a hiatal hernia) but the data again is much less clear. Additionally, since arterial, lymphatic and venous circulation to the legs is frequently quite important, I believe this accounts for why chronically ill patients (who already have compromised fluid circulations in their body) are frequently compelled to start wearing loose pants, and in this instance, they again represent the “canaries in the coal mine” who are warning us against the harms of tight clothing. Trusting Your BodyOne of the major problems we face in life is determining how to make decisions in the face of uncertain information, especially since the funding we rely upon to create our scientific knowledge tends to be biased to arrive at conclusions that make money, not ones that promote health. In turn, as I highlighted in this article, there are a lot of simple things with clothing you would have thought would have been exhaustively studied but never actually have been (whereas as I showed in this article, we frequently spend millions of dollars conducting completely unneeded and inhumane animal experiments—a practice the MAHA H.H.S. is finally taking steps to reduce). Because

of this, I often find we have to rely on alternative ways of knowing,

and one of the most reliable (but frequently dismissed ones) is

listening to our bodies, which for instance is what actually drove me to

adopt the wardrobe I utilize, and similarly drove many of the

chronically ill patients I mentioned above to do the same. My hope in

turn by writing this article is to encourage you to choose clothes on

the basis of how they feel, not how they look. Sadly, our society has done an incredibly effective job in convincing us to not listen to our own intuition so we will continue to be compliant customers. For instance, I’ve lost count of how many heartbreaking pharmaceutical injury stories I’ve heard where the patient stated they felt apprehensive about taking the drug or vaccine, eventually agreed to take it because the doctor badgered them into it, then continued doing so once they experienced severe side effects (which their doctor told them didn’t matter), and that once they became permanently disabled, their greatest regret was not listening to their body and their intuition. One of the main reasons I cited the bra example was to illustrate that despite bras being a modern creation and around half of women stating they do not like wearing them, because of how much money is behind that industry, it’s managed to reshape our society so that most women still do. In the final part of this month’s open thread, I will touch upon the types of clothing we currently endorse wearing (which was the product of years of investigation), and the cosmetic products (e.g., detergents for clothes, soaps and toothpastes) we have found are the least toxic, along with reviewing a few of the more disturbing subjects this article touched upon (e.g., how everything mentioned here relates to some of the more concerning clothing practices transgendered youth are now being encouraged to do and the modern day practices that are recreating abusive clothing practices of the past)... Continue reading this post for free in the Substack app |

No comments:

Post a Comment