Fast Injections = Massive IV Leak: What 10,000 Simulated Vaccine Shots Reveal on the First 8 Minutes Post-Vaccination

Part 1 - My Monte Carlo model shows why rapid delivery sends billions of LNPs straight into the bloodstream — and why slow, gentle injections are dramatically safer

Happy New Year to all of you.

I

wish you and your loved ones a year filled with health, love, joy,

serenity, friendship, and multiple discoveries (hopefully you will find

some here on The Bolus Theory Series).

I pray that the world regains some sense of sanity. More selfishly, I pray the Bolus Theory finally gains the traction it deserves in the population so that the vaccine-injured can discover a path to healing and recovery, and that public health authorities finally acknowledge its significance, and finally end this collective lunacy whereby we are self-inflicting and industrializing so much unnecessary pain and illness.

A couple of days before Christmas, a close friend shared with me that a recent MRI had shown his brain was atrophied…most likely the result of multiple micro-lobotomies caused by repeated vaccine injections…

I am sharing this particularly frightening personal anecdote, not to attract pity, many of you live through much more painful situations, but to highlight that the damage is very widespread in our community, and everyone is touched closely.

The news wasn’t completely a surprise to me, as my most recent work, a computerized modeling of Pfizer vaccine injections, shows that the brain and heart, both organs with limited regenerative capabilities, are systematically carpet-bombed by lipid nanoparticles (an upcoming article will address this in detail).

We need to come to the realization that all vaccinated have been hit¹² (my simulations show that very clearly!).

Many have recovered, but too many haven’t.

Those who were lucky enough to get a slow injection didn’t get a free pass, but did have an unfair advantage with a much lower probability of harm because of an infusion that is more spread out across the first hour. I’ll explain why in the article below.

The devil is in the details.

In medical procedures, procedures executed billions of times, there is no room for approximations.

The professionals who recommended rapid injection to reduce pain and avoid vaccine hesitancy, along with the public health professionals who went along, without assessing the safety aspect of such a change, bear a huge responsibility for the suffering of hundreds of millions of people.

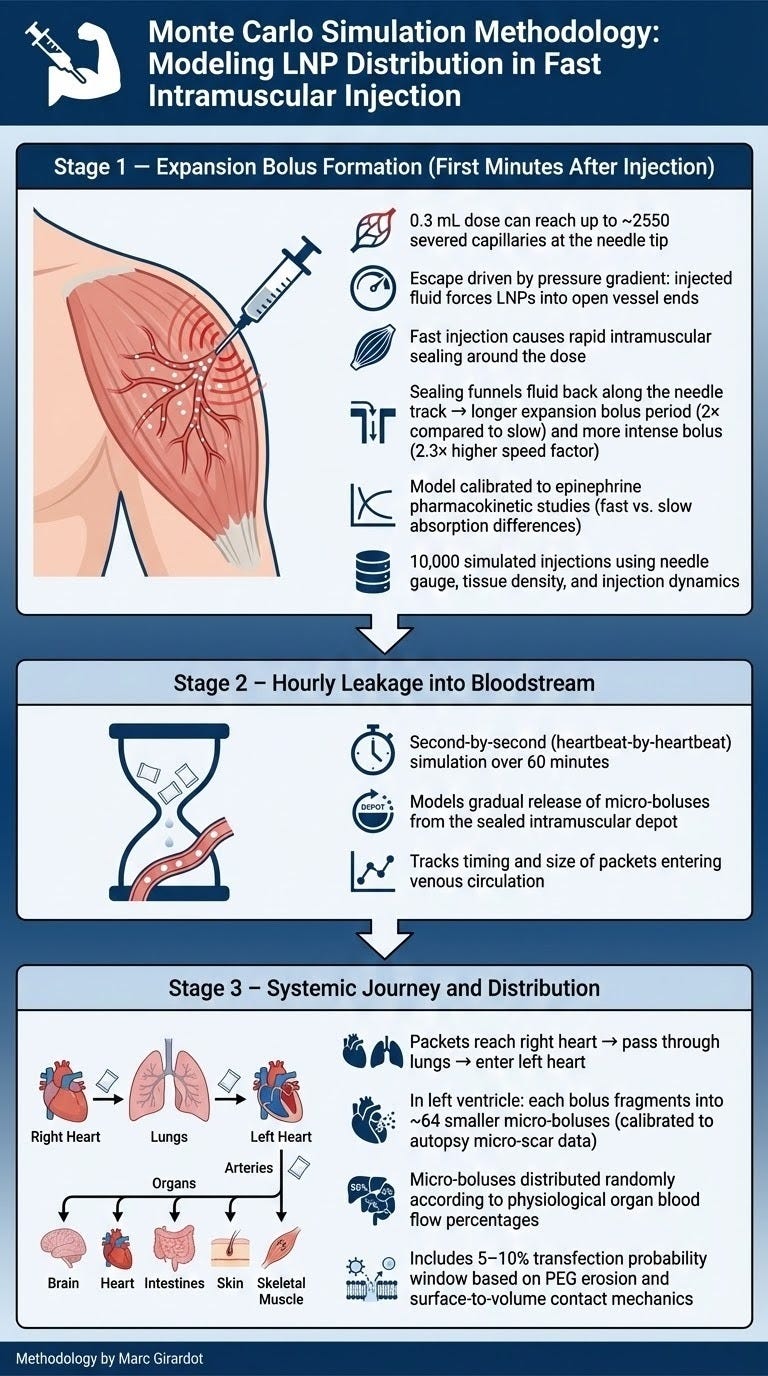

In December, I dedicated all my time to designing and conducting a computerized model of the Pfizer injections, delving into the invisible dynamics that occur as the vaccine penetrates muscle tissue.

I am well aware of the limitations and dangers of models.

My nearly thirty years of experience as a management consultant helped me ensure that the model developed was calibrated at every step, using real data to sanity-check the output. For example, my second-by-second simulation of intravenous leakage over an hour finds that 45% of the dose leaks in IV within an hour, consistent with the Acuitas study (48%).

My purpose in this computerized modeling undertaking (which, frankly, should have been done by paid researchers at NIH et al., not an MBA doing it pro bono with a 2014 Mac) is to reveal what happens beneath the skin throughout the body from the moment the vaccine fluid is injected into the muscle and explain the wide variability of outcomes.

The model and the calibration references forced me to visualize - beyond the generic Bolus concept - what is likely happening when vaccines are injected intramuscularly, how the dose reaches the bloodstream, and where it lands and why.

I

have learnt a great deal of detail about the Bolus Theory, not only

from the outcome of these simulations but also in the process of

building the models. In this article and others to come, I will share

the insights I have uncovered. Hopefully, someone in public health will

read them and finally react…

Herein, I share Stage 1 of my simulation:

What happens in the first 8 minutes: What 10,000 Monte Carlo injections tell us.

(Simulate an injection 10,000 times with different probabilistic outcomes to have a sense of reality.)

This is a big enough number for rare events (outliers) to emerge, as you will see.

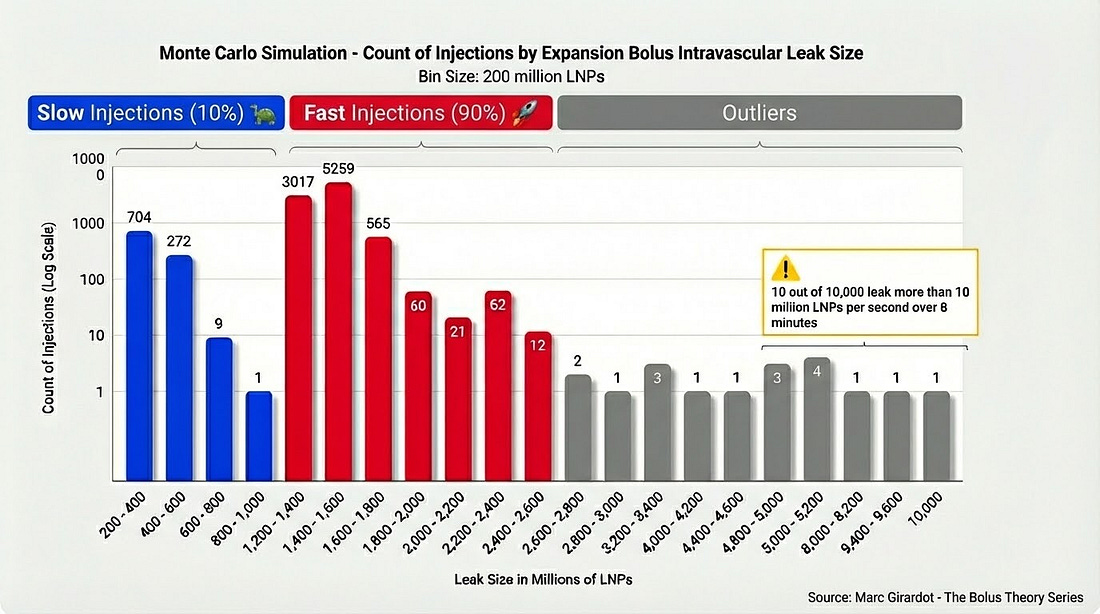

As the vaccine injection protocol states, the injection must be delivered quickly, I decided that 90% of the draws would be “Fast” injections, and 10% would be “Slow”. This choice is likely close enough to reality to be relevant and significant enough to highlight differences between a Fast injection and a Slow injection.

Some of you who read “The Needle’s Secret” or an article I wrote two years ago, “How Many Nanoparticles Directly Go IV?”, will remember I had worked out a way to calculate the size of the dose going directly into the bloodstream when the vaccine was injected. I called it the Expansion Bolus.

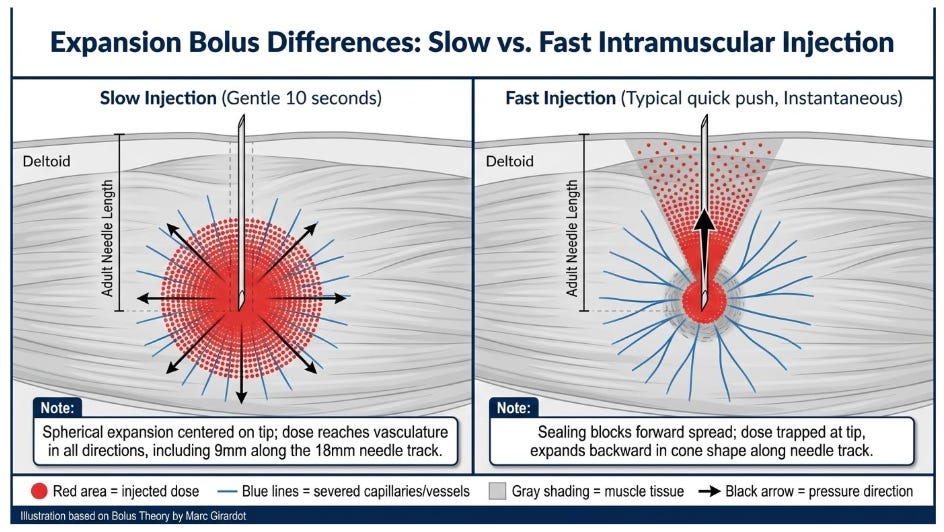

The idea was that - when injected slowly - the dose physically expands in all directions into the muscle and reaches open severed blood capillaries severed by the needle. Depending on the vessel's size and position, the volume of vaccine going IV could be calculated.

Using that formula, the model calculates the individual volume passed through each severed capillary along the needle’s path, based on its size and position.

There’s considerable available data on how much the needle penetrates the deltoid. For simplicity purposes, I considered that the needle penetrates the muscle tissue over 18mm³⁴, and the dose expands over 9mm⁵.

Based on vessel density (450 per sq.mm.)⁶, I estimated that 2,550 small vessels would be severed within the 9mm reach of the vaccine.

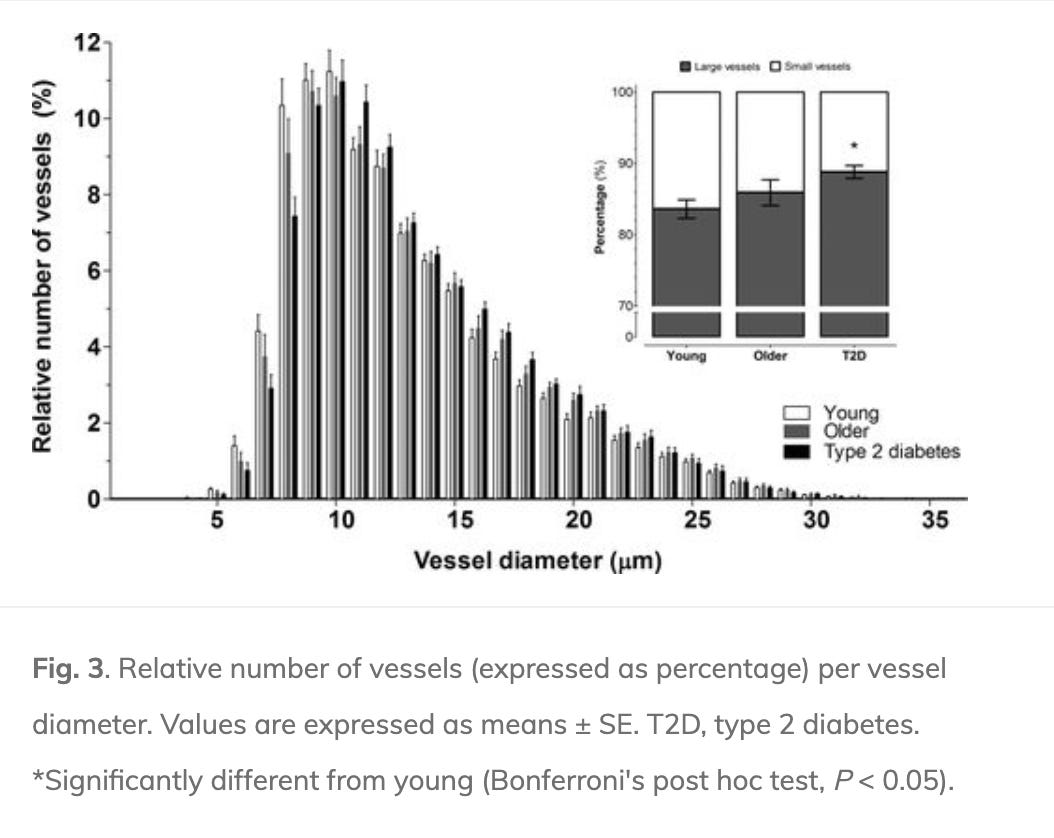

Every injection would be different, cutting through 2,550 vessels of varying sizes and positions. Using available data on frequency across capillary sizes⁷, the model rolls a die for each individual vessel being severed, with most vessels between 8 and 15 micrometers in diameter, and some rare larger vessels.

In other words, in that first simulation, the model simulated 25,5 million leaks through individual capillaries.

However, this calculation, based on physical expansion, doesn’t indicate the speed at which the dose enters the vascular system, which is key.

To calibrate the speed at which the dose goes IV, I used the duration of the expansion bolus as suggested by epinephrine pharmacokinetics studies, which suggest a 0.3mL dose slowly injected intramusculary expands in 4 minutes.

As epinephrine is diluted in saline, and even if vaccine lipid nanoparticles and epinephrine aren’t exactly the same, it is reasonable to assume the dose expands at the same speed (after all, there’s no more difficulty in injecting the vaccine than epinephrine through the needle), and 4 minutes seems like a realistic calibration.

To simulate the difference between a “Fast” injection and a “Slow” injection, the pharmacokinetic⁸ studies of epinephrine⁹¹⁰ were again a relevant calibration source. Interestingly, when injected “Fast” (with an EpiPen), the epinephrine bolus appears to be 2,3 more intense and twice as long (8 minutes instead of 4 minutes). In other words, the model can extrapolate a Fast injection from a Slow injection by multiplying the instantaneous volume flow of a Slow injection by 2.3 and by increasing the duration of the expansion two-fold.

Epinephrine pharmacokinetic studies suggest a fast injection drives a 4.6x quantity of LNP in the first 8 minutes post-injection!

I conjecture that the expansion is longer and more intense when injected rapidly because the dose doesn’t have time to trickle through the cells and vessels, and the cells and vessels facing the needle’s tip are squeezed back and packed by the dose, aggregating to form a liquid-proof seal that temporarily stops the dose from spreading into the tissue. (see graphic above)

Support Independent Research

This work is made possible by paid subscribers. If you find value here, consider joining them.

[Upgrade to Paid – $8/month or $50/year]Therefore, when the needle is retracted, that leaves a natural opening for the vaccine dose to expand into, and more of the dose is funneled to the severed vessels. The expansion also lasts longer because of the sealing of aggregated cells and vessels. When injected quickly, the dose is not permitted to expand spherically across the tissue; it expands backwards towards the needle’s path left empty, and does so for twice as long.

As you can see in the distribution histogram above:

Given the dynamics described, the Slow Injection simulation leakage is much smaller than the Fast Injections with 0.4 Billion nanoparticles going IV in the first 4 minutes (the expansion stalls for a few minutes). Given that the main adverse reaction risk is tied to concentrated transfection, this is a very significant realization. The more progressive the infusion, the safer the injection. You still run the risk of an outlier event (an unfragmented bolus, a small bolus hitting a sensitive place, or large enough vessel in contact with the needle’s tip), but the probabilities would be much smaller, and that means less adverse reactions at a population level.

The Fast Injections average an intravenous leak of 14% of the total dose within 8 minutes. That’s 1.4 billion nanoparticles! All infused directly into the bloodstream at very high concentrations!

I will address where these doses end up in the body in an upcoming article (Stage 2 and 3 of my simulation).Another significant realization is that about 1.2‰ of the injections end up injecting 40+% of the dose in IV, coincidentally, that is the fatality rate as calculated by Pr. Denis Rancourt and his team. Indeed, the larger the bolus, the higher the probability of an unfragmented bolus hitting downstream.

It’s quite clear that the idea of prioritizing once again the fight against vaccine hesitancy by promoting Fast injections was not only a stupid unscientific decision, but a very dangerous one.

Even though it’s not a panacea, based on this simulation, slowing down the injection can save many from harm, notably young infants. A very slow intramuscular protocol would - in my honest pinion - already bring very significant benefits. Those of you who or whose loved ones are still getting shots should make sure the injection isn’t instantaneous, but ideally injected very slowly over a minute or two to limit the risk.

I hope you enjoyed this article and the information it brings to our understanding of the dangers of injecting vaccines quickly into the muscle.

Next week, I will detail where these more than 200,000 micro-boluses end up, and how that ties into the adverse reactions that have afflicted our loved ones.

Feel free to reach out to me with any questions. Feel free to subscribe and become a paying member of The Bolus Theory Series.

I apologize for not writing in a while, but this was heavylifting.

After spending some time with my family during the Christmas break, I am back in the mountains alone, working to get the Bolus Theory off the ground. Please make sure you share the word.

I apologize if this piece is a bit technical, but someone needed to do it. I sincerely hope you enjoyed it, as it has demanded a lot of brain power and head scratching.

Love, Marc

“Assessment of Myocardial 18F-FDG Uptake at PET/CT in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2–vaccinated and Nonvaccinated Patients” by Nakahara et al. - Reference

“Sex-specific differences in myocardial injury incidence after COVID-19 mRNA-1273 Booster Vaccination” by Buergin et al. - Reference (see appendix for leak differential pre and post-vaccination)

“Bioavailability and Cardiovascular Effects of Adrenaline Administered by Anapen Autoinjector in Healthy Volunteers”“ by Duvauchelle et al. - Reference

“Skeletal muscle capillary density and microvascular function are compromised with aging and type 2 diabetes” by Groen et al. - Reference

I considered that muscle cells represent 90% of the volume, and therefore, the expansion can only happen by pushing interstitial fluid, but 90% of the volume still contains muscle cells and capillaries.

“Histological analysis of the medial gastrocnemius muscle in young healthy children” by Andries et al. - Reference

“Skeletal muscle capillary density and microvascular function are compromised with aging and type 2 diabetes” by Groen et al. - Reference

Pharmacokinetic: what happens to a medicine after you take it—how it gets absorbed, where it spreads in the body, how it’s broken down, and how it’s removed.

“Epinephrine delivery via EpiPen® Auto-Injector or manual syringe across participants with a wide range of skin-to-muscle distances” by Worm et al. - Reference

“Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic comparison of epinephrine, administered intranasally and intramuscularly: An integrated analysis” by Tanimoto et al. - Reference

You're currently a free subscriber to The Bolus Theory Series. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

No comments:

Post a Comment