Potential Health Impact of Microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects

I

am a member of the American Chemical Society. Aside from the

nanotechnology literature, ACS has been consistently publishing

excellent scientific papers on the findings of microplastics in human

tissues. This review article is eye opening, for the overlap of the

microplastics toxicity to also vaccine injury that uses polymer plastics

stealth nanoparticles as well as the geoengineering of polymers that

people inhale and also contaminate our biosphere.

The

bottom line is that these chemicals are toxic for humanity. Why are

they allowed in medications and vaccines? I believe that the acclerated

aging process we have been seeing is caused by the enormous burden of

self replicating nano and microplastic polymers that are in the blood

and penetrate to every organ system. The self assembly nanoparticles are

what create the polymers in the blood, it is not just the microplastic

exposure from environmental sources as I have shown before.

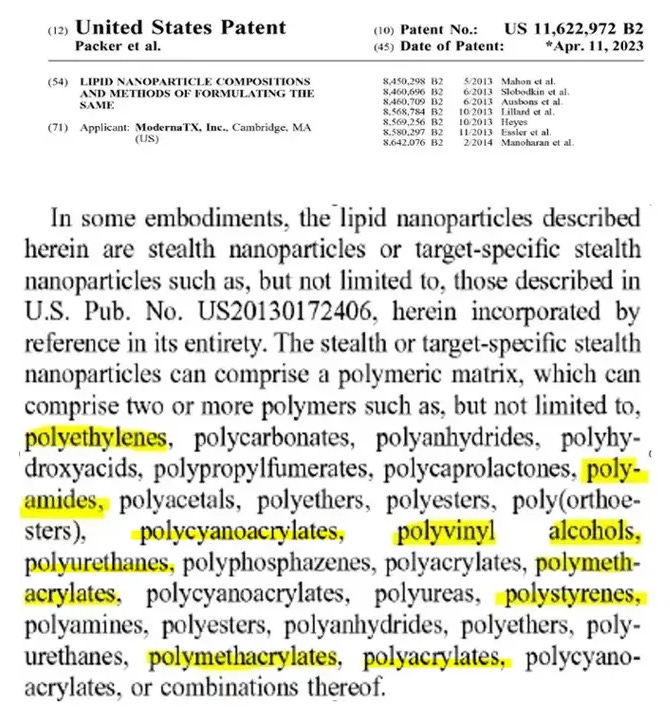

Please

note that all of these plastics are also stealth nanoparticles in the

Moderna patent:

___________________________________________________________________________

A

recent review indicates that microplastics are transported to the whole

body through blood circulation, and the existence of microplastics are

found in 15 human biological components, such as the spleen, liver,

colon, lung, feces, placenta, breastmilk, etc. (58) The organs with high

content are the colon (28.1 particles/g) and liver (4.6 particles/g).

The main types of microplastics detected include PE, PET, PP, PS, PVC,

and PC.

(Polyethylene, Polyelthylene Terephtalate, Polypropylene, Polystyrene, Polyvinyl Chloride, Polycarbonate)

__________________________________________________________________________

Video:

COVID19 unvaccinated blood. Micellar construction site filled with

nanorobots building a mesogen polymer microchip. Magnficiation 2000x.

Please read this interesting and eye opening article:

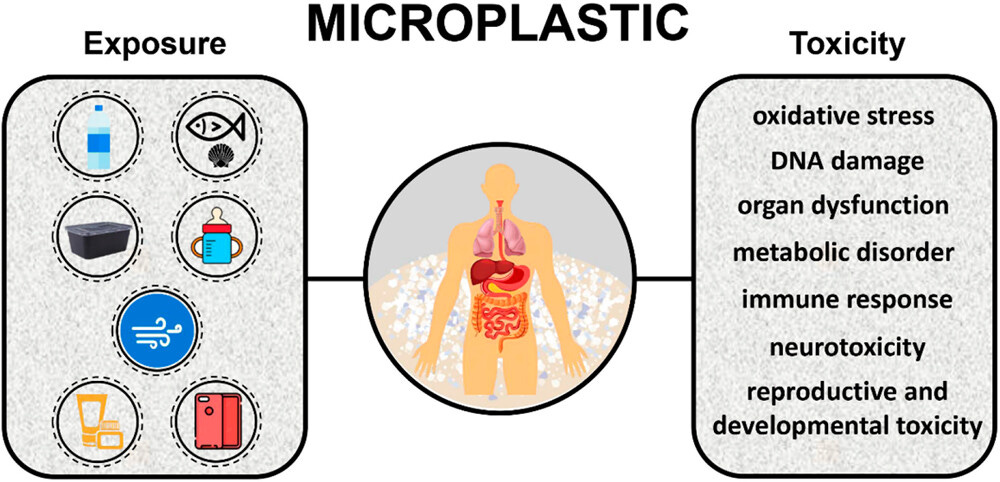

Microplastics

are ubiquitous in the global environment. As a typical emerging

pollutant, its potential health hazards have been widely concerning. In

this brief paper, we introduce the source, identification, toxicity, and

health hazard of microplastics in the human. The literature review

shows that microplastics are frequently detected in environmental and

human samples. Humans are potentially exposed to microplastics through

oral intake, inhalation, and skin contact. We summarize the toxic

effects of microplastics in experimental models like cells, organoids,

and animals. These effects consist of oxidative stress,

DNA damage, organ dysfunction, metabolic disorder, immune response,

neurotoxicity, as well as reproductive and developmental toxicity. In

addition, the epidemiological evidence suggests that a variety of

chronic diseases may be related to microplastics exposure. Finally, we

put forward the gaps in toxicity research of microplastics and their

future development directions. This review will be helpful to the

understanding of the exposure risk and potential health hazards of

microplastics.

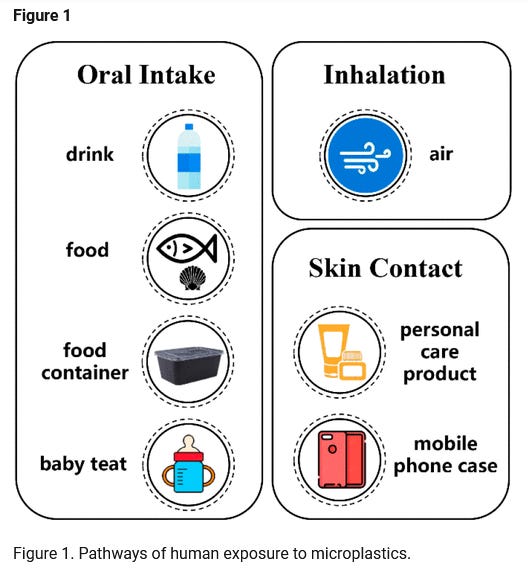

Microplastics

exist in our daily necessities like drinking water, bottled water,

seafood, salt, sugar, tea bags, milk, and so on. (21−29) Europeans are

exposed to about 11,000 particles/person/year of microplastics due to

shellfish consumption, (30) and according to food consumption, the

intake of plastic particles in human body is 39,000–52,000

particles/person/year. (31) Microplastics may also have been widely

distributed in soil, especially in agricultural systems. (20) They

(especially with negative charge) can get into the water transport

system of plants, and then move to the roots, stems, leaves, and fruits.

(32,33) Once microplastics enter agricultural systems through sewage

sludge, (34) compost, (35) and plastic mulching, (36) they will cause

food pollution, which may increase the risk of human exposure.

Take-out

food containers made of common polymer materials (PP, PS, PE, PET) are

used widely, from which microplastics are found. (37,38) It is estimated

that people who order take-out food 4–7 times weekly may intake 12–203

pieces of microplastics through containers. (38) In addition, research

demonstrates that the surface of silicone rubber baby teats degrades

when they are sterilized by steam, during which microplastic particles

are released into the environment. (39) It is estimated

that the total number of microplastic particles entering the baby’s body

during one year of normal bottle feeding reaches about 0.66 million.

Microplastics

in the air are mainly PE, PS, and PET particles and fibers with size

ranges of 10–8000 μm. (40) The largest source of microplastics (84%) in

the atmosphere comes from the road. (41) It is reported that the median

concentration of microplastic fibers is 5.4 fibers/m3 in the outdoor air and 0.9 fibers/m3 in the indoor air in Paris. (42) The average concentration of microplastics is 1.42 particles/m3

in the outdoor air in Shanghai, and the size range is 23–5000 μm. (43)

It is estimated that annual microplastics consumption ranges from 74,000

and 121,000 particles when both oral intake and inhalation are

considered. (31) Amato-Lourenço et al. detected microplastic particles

smaller than 5.5 μm and microplastic fibers with the size of 8.12–16.8

μm in human lungs, whose main components are PE and PP. (44) The size of

microplastics detected in lung tissue is smaller than that in the

atmosphere. This further confirms that humans can be exposed to

microplastics by inhalation and prompts attention to the potential harm

to the human body.

Microplastics

are usually considered not to pass through the skin barrier, (45) but

they can still increase exposure risk by depositing on the skin. (46)

For example, the use of consumer products containing microplastics (such

as face cream and facial cleanser) will increase the exposure risk of

PE. (47) The protective mobile phone cases (PMPCs) can generate

microplastics during use, which are transferred to human hands. (48)

When children crawl or play, they may come into contact with

microplastics on the ground. During the dermal exposure

of microplastics, some typical plastic additives, including brominated

flame retardants (BFRs), bisphenols (BPs), triclosan (TCS), and

phthalates, may be absorbed. (49)

Microplastics

are found in animals. They pose a great threat to aquatic organisms,

like fish and marine mussels. Microplastic fibers are the most frequent

microplastic type ingested. (50) All fishes in the Haizhou Bay have

microplastics with the highest abundance of 22.21 ± 1.70

items/individual. (26) Mussels in the French Atlantic

coast and the coastal waters of the U.K. both have microplastics.

(27,51) For wild coastal animals, microplastics are found in their

intestine, stomach, liver, and muscle. (52) PET is also detected in the

feces of pets, such as cats (<2300–340,000 ng/g) and dogs

(7700–190,000 ng/g). (53) Microplastics also exist in plants and algae.

Liu et al. carried out a hydroponic experiment, which they confirmed

using confocal laser scanning microscopy that microplastics can transfer

from roots to the aboveground parts of rice seedlings. (54)

Yan et al. reports that microplastics are internalized in the vacuoles

of algal cells. (55) It is noteworthy that the phenomenon of biological

endocytosis of microplastics can be utilized to remove microplastics

from the environment. Manzi et al. summarizes the algal species that

have been used to remove microplastics from the aquatic environment and

highlights the mechanism of microplastics biodegradation. (56)

It

is generally believed that after entering the human body, microplastics

will be excreted out through the gastrointestinal tract and biliary

tract. However, researchers detect the existence of microplastics in

human blood. (57) People begin to reconsider the harm of microplastics

to human health. The intake, distribution, accumulation, and metabolism

of microplastics in the human body are attracting more and more

attention. Understanding the concentration of microplastics in the human

body is an important prerequisite for exploring their potential harmful

effects. A recent review indicates that microplastics

are transported to the whole body through blood circulation, and the

existence of microplastics are found in 15 human biological components,

such as the spleen, liver, colon, lung, feces, placenta, breastmilk,

etc. (58) The organs with high content are the colon (28.1 particles/g)

and liver (4.6 particles/g). The main types of microplastics detected

include PE, PET, PP, PS, PVC, and PC.

Pregnant

women and infants are sensitive people exposed to microplastics. (59)

The concentration of PET in infant feces (5700–82,000 ng/g, median:

36,000 ng/g) is ten times higher than that in adults (2200–16,000 ng/g,

median: 2600 ng/g), (60) indicating that the exposure level of

microplastics in infants may be much higher than adults. Twelve

microplastic fragments, ranging from 5 to 10 μm, are detected in human

placenta by the team of Ragusa for the first time, (61) and then they

first detect PVC and PP microplastics with a size of 2–12 μm in human

breastmilk. (62) Since then, more studies also detect microplastics in

placenta, meconium, and breastmilk. Zhu et al. detects microplastics in

17 placental samples and identifies 11 types of polymers with sizes from

20.34 to 307.29 μm. (63) Liu et al. recruits 18 pairs of mothers and

infants and determines 16 types of microplastics in placenta, meconium,

infant feces, breastmilk, and infant formula samples. (64) More than 74%

of microplastics are 20–50 μm in size. In accordance with the DOHaD

theory, adults experiencing adverse factors in the early stages of

development will increase the probability of obesity, diabetes,

cardiovascular disease, and other chronic diseases in adulthood. (65) The

appearance of microplastics in human placenta further emphasizes that

these nondegradable chemicals have potential intergenerational influence

on the human body and may affect the developing fetus. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the potential impact of early exposure of infants and early development of embryos.

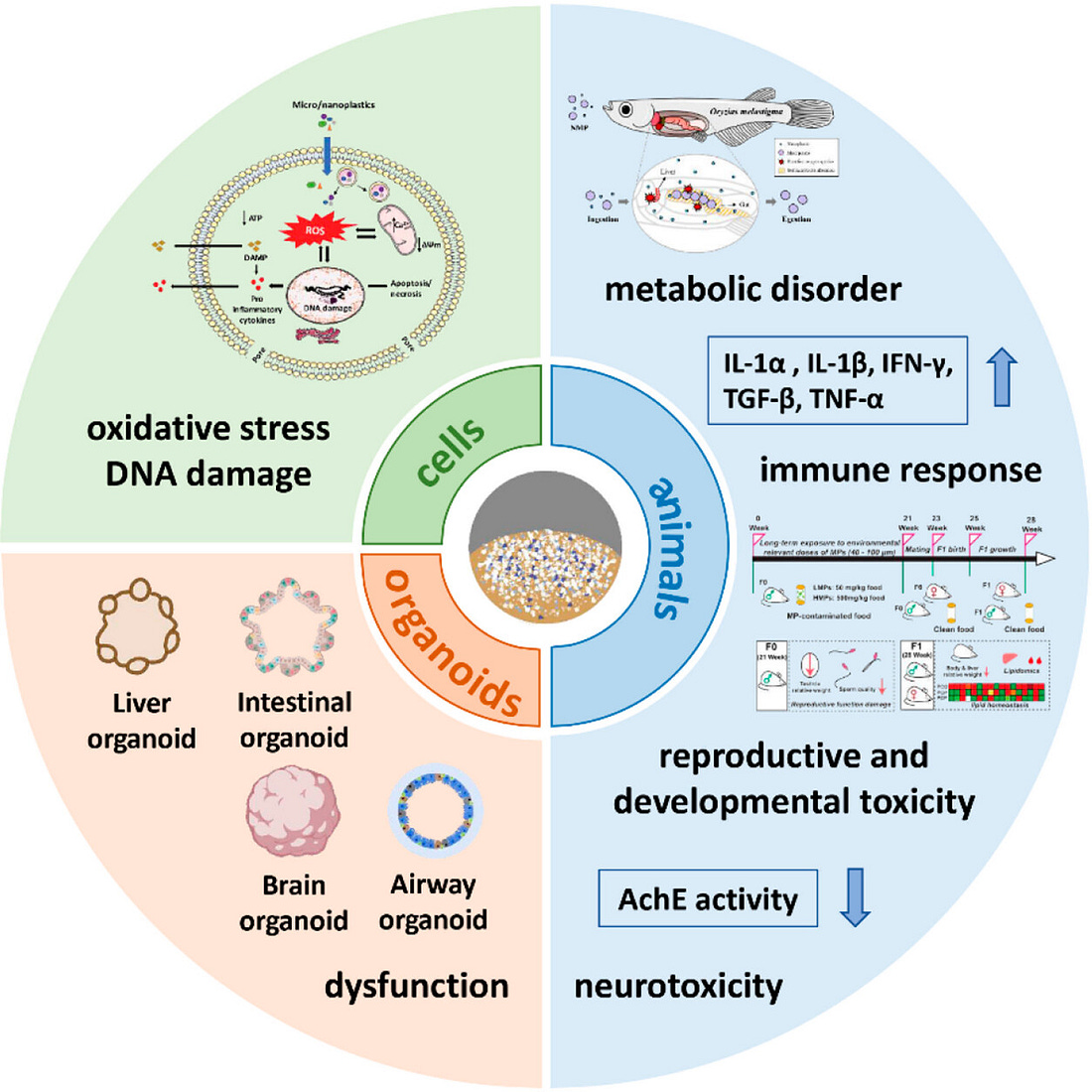

Microplastics

producing toxic effects is a complex process and is affected by many

factors including the physical and chemical properties, exposure time,

additives, etc. Microplastics are not only toxic itself but also

carriers for many pollutants to enter biological tissues and organs. We

aim to systematically sketch their potential toxicity at the

“individual-tissue-cell-subcellular” level, which will help to explore

the toxicity mechanism. Due to the lack of direct research from humans,

this section briefly summarizes the major effects of microplastics in

present experimental models, like cells, organoids, and animals (Figure 2).

Previous

animal experiments confirm that microplastics lead to the dysfunction

of the liver and intestine. For instance, Kang et al. finds that

microplastics induce intestinal damage of fish by two different

mechanisms. (83) PS with size of 50 nm exhibits stronger oxidative

stress, while PS with size of 45 μm causes significant imbalance of

intestinal flora. Kim et al. reports that microplastics lead to the

inhibition of digestive enzyme activity in fish through a

microalgae-crustacean-small yellow croaker food chain. (84) Jin et al.

also reports that intestinal barrier and metabolic function are impaired

in PS exposed mice. (85) Tan et al. demonstrates that microplastics

significantly reduce lipid digestion in the simulated human

gastrointestinal system, and PS shows the highest inhibition. (86) The

decrease of lipid digestion is independent of PS size. Lu et al. reveals

that PS exposure causes the local infection and lipid accumulation in

the liver of fish and disrupts the energy metabolism. (87) In addition,

Deng et al. discovers that after exposure to microplastics and

organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs), the metabolites of mice

change significantly. (88) And it is noticeable that microplastics

aggravate the toxicity of OPFRs, highlighting the health risks of

microplastic coexposure with other pollutants.

Microplastics

can induce immune response in the body. Yuan et al. reports that PE

exposure activates the intestinal immune network pathway of zebrafish

and produces mucosal immunoglobulin. (89) Li et al. demonstrates that

the secretion of IL-1α is increased in the serum of rats exposed to PE

but decreased in the Th17 and Treg cells among CD4+

cells. (90) Lim et al. observes that inhalation of PS causes the

upregulated expression of the inflammatory protein (TGF-β and TNF-α) in

lung tissue of rats. (91) Liu et al. finds that PS exposure

significantly increases the expression of inflammation factors (TNF-α,

IL-1β, and IFN-γ) in mice, and intestinal immune imbalance will

significantly increase the accumulation of microplastics, producing

further toxic effects. (92)

Microplastics

are also toxic to the neural development. Inhibition of

acetylcholinesterase (AchE) activity is the most reported neurotoxic

effects after the exposure of microplastics. (93) In a study of juvenile

fish, the microplastics inhibit the activity of AchE, increase lipid

oxidation in the brain, and change the activities of energy-related

enzymes, eventually causing neurotoxicity. (94) Prüst et al. also

reports that microplastics cause the abnormal behavior of nematodes,

crustaceans, and fish. (93) Yang et al. discovers that PS (70 nm) can

pass through the epidermis of larvae and enter into the muscle tissue.

(95) It can destroy nerve fibers, decrease the activity of AchE, and

exert great adverse effects on larval movement. Besides, Jin et al.

reveals that after the chronic exposure to PS at environmental pollution

concentrations (100 and 1,000 μg/L), the blood-brain barrier of mice is

damaged, and the learning and memory dysfunctions occur. (96)

The

effect of microplastics on reproduction is reflected in the development

of germ cells and embryo quality. For example, Liu et al. finds that

the PS exposure affects the development of female mouse follicles and

the maturation of oocytes, reducing the quality of oocytes. (97) And Hu

et al. reports that microplastics might cause adverse effects on

pregnancy outcomes through immune disorders. (98) Deng et al. finds that

after long-term exposure to environmentally relevant doses of PS, the

sperm quality significantly decreases, which affects the fertility of

male mice. (99) In addition, Park et al. shows that the number of live

births per dam and the sex ratio and body weight of pups in groups

treated with PE are notably altered. (100) What’s more, they suggest the

IgA level as a biomarker for harmful effects following exposure on

microplastics.

Epidemiological

investigation is a good method to demonstrate the correlation between

microplastics exposure and adverse health outcomes. However, there are

relatively few epidemiological studies related to microplastics. Kremer

et al. reports that due to occupational exposure, workers in polymer

factories in The Netherlands are more likely to suffer from chronic

respiratory diseases. (101) In Canada and the United States, nylon

flocking factory employees are diagnosed with work-related interstitial

lung disease. (102) Yan et al. discovers that the fecal microplastic

concentration in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients is

significantly higher than that in healthy people, and the concentration

is positively correlated with the degree of IBD. (103) Horvatits et al.

finds the existence of microplastics in cirrhotic liver tissues, whose

concentration is higher compared to that of liver samples from healthy

individuals. (104) Wu et al. detects the existence of microplastic in

human aortic dissection thrombus samples and human acute arterial

embolism samples. (105) These results suggest that microplastics may be

associated with the formation of many chronic diseases, which may be

harmful to human health.

Humans

are exposed to microplastics by oral intake, inhalation, and skin

contact. Microplastics have been found in a variety of organisms and

multiple parts of the human body. We emphasize the potential impact of

microplastics on the early exposure of infants and the early development

of embryos. At present, the toxicity research on microplastics show

that the exposure will cause intestinal injury, liver infection, flora

imbalance, lipid accumulation, and then lead to metabolic disorder. In

addition, the microplastic exposure increases the expression of

inflammatory factors, inhibits the activity of acetylcholinesterase,

reduces the quality of germ cells, and affects embryo development. At

last, we speculate that the exposure of microplastics may be related to

the formation of various chronic diseases. Although the

toxicity of microplastics has been widely studied, there are still

several key scientific issues that need to be further explored: (1) The

key technologies for precise identification, multiscale

characterization, and accurate quantitative and dynamic tracing of

microplastics in organisms. At present, the commonly used analytical

means can detect microplastics only at the micron level, and it is

difficult to effectively analyze microplastics with smaller size

(nanoplastics) and greater potential harm, which brings great challenges

to accurately reveal the possible health risks of microplastics. In

addition, there is still a lack of effective dynamic tracing means.

Therefore, how to precisely identify, accurately quantify, and

dynamically trace the microplastics in organisms is the primary problem.

It may be improved by comprehensively utilizing existing imaging and

analysis technologies, such as SEM, CLSM, Raman spectroscopy, and so on.

(2) The biological processes such as absorption, metabolism,

transportation, and accumulation of microplastics, as well as crossing

biological barriers. Although studies have shown that microplastics can

enter the circulatory system and reach other tissues, from the current

research results, one cannot clearly determine the key factors of the

bioprocess of microplastics. Systematic research on the key biological

processes of microplastics needs to be carried out at the

“individual-tissue-cell-subcellular” level. The content includes but is

not limited to the transport process, the distribution in tissues and

organs, the single cell atlas, and the intracellular localization. (3)

The “common” and “specific” characteristics of biological processes of

different microplastics. There are various kinds of microplastics with

different sizes and physical and chemical properties. However, the

current experiments usually use PS and PE as models, and most of them

are commercially synthesized, which means the type of microplastic is

unitary. Therefore, more kinds of microplastics (e.g., actual

environmental samples) need to be used in the exposure experiments, and

their commonness and specificity should be revealed. (4) The “real”

quantitative relationship between the exposure dose and toxic effects of

microplastics, as well as the combined toxic effect of microplastics

and other pollutants. Although scientists have found some toxic effects

about the exposure of microplastics using multiple experimental models,

they usually use high exposure doses. It is necessary to evaluate the

toxic effects of microplastics more realistically from the perspective

of actual environmental concentration and the whole life cycle of

organisms. Because of the large surface energy, microplastics usually

adsorb other pollutants, especially heavy metals and hydrophobic organic

chemicals. The combined toxicity needs further investigation to explore

whether there is synergy between microplastics and adsorbed pollutants

and the toxic mechanism. (5) The key determinants and molecular

mechanisms of toxic effects of microplastics. At present, the research

on the toxicity of microplastics is mostly effect analysis, and the

molecular mechanism is relatively lacking. It is necessary to combine

the multiomics analysis with toxicity effect study, in which the

exposure and effect biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity may

be screened. (6) The correlation between microplastics and adverse

health outcomes. Almost all the studies on the toxicity of microplastics

use experimental models, and the harm to the human body is still

unclear. Epidemiological and clinical data needs to be collected.

Biomarkers can be used to explore the internal relationship between

microplastic exposure and possible adverse health outcomes. A health

risk assessment model should be established with the help of machine

learning to early warn the exposure risk of microplastics.

Unbelievable

Amounts Of Nano & Microplastics Found In Deceased Human Brains -

Concentrations Rose by 50% between 2016-2024. The Rise Of Human Cyborgs:

Instead Of Superintelligence We Get Dementia?

Study Shows How Microplastics Can Easily Climb The Food Chain

Microplastics

in Human Blood: Polymer Types, Concentrations and Characterization

Using μFTIR Microplastics in Human Blood: Polymer Types, Concentrations

and Characterization Using μFTIR

Microplastics in Human Blood: Polymer Types, Concentrations and Characterization Using μFTIR

New

Study: "Microplastics in the Olfactory Bulb of the Human Brain" Finds

Polypropylene, Nylon, Polyamide Microplastics. We Found This In The

Blood Too, And Call It Self Assembly Nanotechnology

Humans Turning Into Cyborgs: Scientific Article On "Detection of Various Microplastics in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery"

Microplastics - aka Nanotechnological Self Assembly Polymers - Are Everywhere - Poisoning Our Biosphere, Food Supply And Humans

New England Journal Of Medicine Microplastics Article Shows Higher Risk Of Heart Attacks, Stroke And Death

No comments:

Post a Comment