Remembering the Paris Commune Marking the 152nd anniversary of “La Semaine Sanglante”

Catte Black

The original version of this article was first published in the before times – back in the heady days of 2015 – when OffG was only a few weeks old, and our readership could be counted on the fingers of an inattentive lathe operator. Since, this year, the anniversary falls on a Sunday, making it 152 years literally to the day, we thought it was time to bring this back. Its relevance has not diminished, only grown, now that the “violence inherent in the system” has been so freshly demonstrated on a global scale in the past few years.

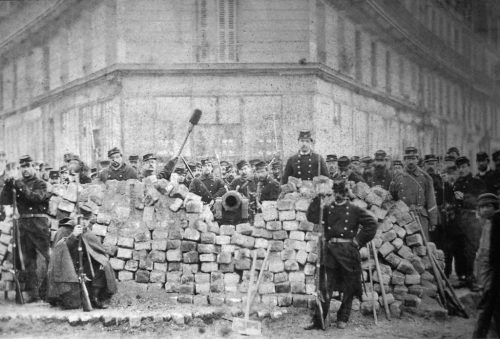

Today marks the 152nd anniversary of “La Semaine Sanglante” – the final and bloody suppression of the revolutionary Paris Commune of 1871, by French government forces.

It’s timely to recall this incident now, as the legendary Paris Commune has always been a symbol for all sides in the eternal struggle, being seen as both a ghastly example of the wretched anarchy that results from the breakdown of social order, and as a beacon of egalitarian social justice. Its ruthless suppression has been portrayed as both essential for the reassertion of proper order, and as a glaring example of “the violence inherent in the system.”

So, to briefly summarise the background. On 19 July 1870, France declared war on Prussia, for reasons that doubtless seemed good to them (or at least their war-barons) at the time, but which proved disastrous for the country and for the incompetent and ridiculous “Emperor” Napoleon III (the real Napoleon’s nephew, with all of his ego and none of his talent).

According to Wiki the wily Bismarck “adroitly created a diplomatic crisis” and thereby tricked the French Assembly into voting for war. However Adam Gopnik in the New Yorker claims France:

stupidly provoked a war with Bismarck’s rising Prussia for the usual reasons that demagogic governments stupidly provoke wars: because bashing the nasty next-door neighbor seemed likely to boost the boss’s prestige…

Whatever the cause France was soon in deep trouble, with the Prussian army swarming over French soil, and on September 4 1870, just six weeks after boldly declaring war, Paris was under siege and Napoleon III was forced to abdicate, leaving France at the mercy of the Prussians and its own incompetent National Assembly.

Prudently locating itself in Bordeaux, far from its own besieged capital city, this Assembly proceeded to further mismanage the already hopeless war. Elections held during this period of turmoil returned a majority of right wing republicans and Bonapartists, and a new President, Adolphe Thiers, who was one of this number.

This Thiers allegedly felt he had no choice but to sign a humiliating peace deal that ceded large amounts of French territory to the Prussians and allowed them to do a victory march through the streets of Paris.

As can be imagined, this did not go over well with the Parisians, who had just endured six months of crippling hardships under the siege, eating rats and leather belts to survive. They understandably felt betrayed by this geographically and experientially distant government. According to the ex-Comunard Lissagaray:

The Prussians entered Paris on the 1st March. This Paris which the people had taken possession of was no longer the Paris of the nobles and the great bourgeoisie of 1815. Black flags hung from the houses, but the deserted streets, the closed shops, the dried-up fountains, the veiled statues of the Place de la Concorde, the gas not lighted at night, still more pregnantly announced a town in its agony. Prostitutes who ventured into the quarters of the enemy were publicly whipped. A café in the Champs-Elysées which had opened its doors to the victors was ransacked. There was but one grand seigneur in the Faubourg St. Germain to offer his house to the Prussians.

But this was only the beginning of what the Thiers government decided to inflict on Paris.

Despite the fact the siege had impoverished so many Parisians the Assembly voted not to suspend or waive payment of outstanding rents and bills – raising the real prospect of homelessness or debtor’s prison for many.

It then relocated itself from Bordeaux to Versailles – not Paris – which seemed like a calculated insult to the city that had endured so much. And it appointed Bonapartists to govern the staunchly republican and left-leaning population.

The sense of outrage only grew, and in a city still militarised following the prolonged siege, with large numbers of its able-bodied men still in the National Guard and trained in the use of weaponry, the potential dangers of this volatility were obvious – to everyone it seems but the government, which continued to to nothing but provoke.

Paris had the choice either of self-determination or of total subjugation to a government that had chosen for whatever reason to entirely ignore the city’s interests and refused to respect its wishes.

The spark to the powder keg was a dispute over the ownership of some cannons. The details don’t matter. The results were inevitable. The government forces were met with disorganised grassroots resistance when they attempted to appropriate the cannons, and were driven out of the city.

The Committee of the National Guard and a hodge-podge of radicals and opportunists rushed to fill the void left by this departure.

The first thing the ad hoc new governors of Paris did was organise elections for a city council – a Commune.

The response of the Thiers government in Versailles was to rather petulantly order the people of Paris not to vote or recognise the election, and many middle class Parisians did stay away from the polls. So, it was no surprise when the resulting body, elected March 26, was dominated by many shades of left wing radicals from old style Jacobins to socialists, Proudhonists and Communists.

Once elected the new radical Commune began several programs of wide ranging social reform which would have been ambitious in a new national government but in an impoverished city under siege by it own National Asembly was optimistic to the point of delusion.

At this point the National government in Versailles could still have responded with tact and negotiation. The elections may have resulted indirectly from a slight coup, they may not have been approved, and they may have had a low-ish turnout, but they had been reasonably free and fair and it was an undeniable right of the people of Paris to elect their own city council. Thiers and his cabinet could have recognised this, remembered the sacrifices Paris had made for the war, accepted the reality of the new Commune and tried to work with it.

But no.

With new radical communes spontaneously breaking out in Marseilles and other provincial cities, the government apparently believed force was the key. They decided to treat Paris as a city once again under siege – this time by its own government. They closed down rail access in and out of the city, closed down the mail service, and on April 1 Thiers announced:

The Assembly is sitting at Versailles, where the organization of one of the finest armies that France has ever possessed is being completed. Good citizens may then take heart and hope for the end of a struggle which will be sad but short.”

Many people in Paris believed the French army would simply refuse to fire on its own people, and some Communards were sure all that was needed would be an expedition to Versailles to win over the troops there and seal the fate of the national government.

The delusion behind this thinking was tragic. Their under-armed, under-trained “expeditionary” forces were met with full assault and fled in disarray. Anyone captured was summarily shot by the Versaillais.

By early May Paris was being routinely shelled from the outlying forts.

May 21 the government troops entered by the Issy gates. The Communards, outnumbered and outgunned, fought hard, and it took seven days of street fighting for the Versaillais to take the city.

Many streets were turned to rubble. The Tuileries Palace and the medieval Hotel de Ville were burned to the ground. Each side blaming the other for that.

The resultant massacres and summary executions of the losers by the victors are too well known to need development. Some 10-17,000 people died. Order was restored. The gold in the banks was rescued before it could be used to benefit lowly people who did not deserve it.

It proved handy in paying off the Prussians for the war.

Today the horror of Bloody Week is starting to get the same makeover that WW1 received recently. Sanding off the harsh realities, repackaging as something softer, saner – maybe almost, if not quite, a good thing. Necessary anyway.

The Brave New World of goodies and terrorists has no room for tragedies of this kind. They stir up dormant questions in the populace.

Why is government sanctioned murder always ok?

Are things really being run in our best interests or are we just hapless pawns?

What exactly is a terrorist anyway?

Questions even our regular doses of soma can’t suppress. Best to just airbrush them into something else. Make them all go away.

Notes & Sources

History of the Paris Commune, by Prosper Olivier Lissagaray

Documents of the Paris Commune

Wiki’s completely unbiased account of the Paris Commune .

Robert Graham’s Paris Commune blog

No comments:

Post a Comment