People of the Lie

A Meditation on a Book by M. Scott Peck

“Satan wants to destroy us. It is important that we understand this.” —M. Scott Peck, People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil

When I was in high school, I had a brief run as a motocross racer. I’d bought, with my own money, a small 125 cc Suzuki street motorcycle and stripped off both its head and tail lights to race on bumpy, winding, circular, dirt tracks in what I then considered to be the hinterlands of upstate New York and eastern Pennsylvania. I’d load the bike on a rack I’d attach to the back of my mother’s station wagon and, from our suburban Connecticut home, I would drive myself two or three hours to whatever race was happening on a particular weekend. There were a couple of friends of mine who were also on this small, low-budget racing circuit.

I had started out with a bigger motorcycle for street riding. My parents and I repeatedly feuded over this until they ultimately gave in; I’d worn them down as only an eager and annoying teenager could do. After a year or so, when I told them I wanted to switch to motocross racing, I said it was safer than riding on the street. That actually made sense to me. On a dirt track, you’re not battling cars and trucks going this way and that, and where if you wandered or slid into oncoming traffic, or off the road, your death was almost certain. My parents believed me because I believed it myself.

At these races, I often saw a middle-aged man taking photographs of all the motorcyclists on the race course. He’d position himself at hairpin turns, or on a hill, to capture riders flying into the air or riding on just the rear wheel like horsemen breaking in wild stallions. Then, at the next race, he’d show up with hundreds of 8 x 10-inch black and white photos of the racers. You went through them and if you found one of yourself you liked, he’d sell it to you. It was a fun memento.

My time spent racing was brief. During one race my first summer, dozens of us were all speeding along on a muddy track made slick by a daylong drizzle and I fell in front of another motorcycle, whose front wheel rammed into my left rib cage. I was knocked close to unconsciousness and I could hardly breathe. An ambulance rushed me to the local hospital; one of my ribs had been broken and it nearly punctured my left lung. When I got home, I told my parents what had happened. I lifted my T-shirt to show them the elastic brace around my torso and my father cut in triumphantly, “That’s it. No more motorcycles for you.”

I sold my “dirt bike” but I still borrowed my mother’s car to drive to the race tracks to watch. I was an amateur photographer at the time and so I took photos of my friends. I had my own darkroom in the basement of our family’s home and gave my photos away. At one point I was approached by this same photographer—turned out he was from Queens, New York—who’d been coming to the races. I showed him my work and he asked me if I wanted to start shooting for him. He would pay me. Thrilled at the opportunity to make some money with my camera, I accepted. At each race, he’d give me a half-dozen or so rolls of black and white film, and I’d spend the day shooting hundreds of photos. I’d give the exposed film back to him, and then when he developed the photos I’d taken, he’d mail me a check for my work.

During my freshman year at college in New Hampshire, he called me to ask if I wanted to shoot a motorcycle rally in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. Again, I was thrilled. I started thinking I could have this side hustle taking photos of motorcycle races to help pay for my expenses at college.

The race took place over a weekend, so we had to spend a night in a cheap motel near the race course. After a day of shooting, we both went to bed early so we could get up at first light the next day and continue. Although the room had two double beds, I was not comfortable sharing a room with a stranger. I didn’t want to pay for my own room, however, and spend most of the money I was going to earn.

When I got out of the bathroom, the man was already in his bed near the window. I climbed into my bed and turned off the light. After I moment, he said into the darkened room, “Do you want to come over here?”

“No, I’m good,” I said nonchalantly. But I was alarmed. I had not seen this coming. It was the furthest thing from my mind, in fact. I kept calm.

“Why not?” he asked.

“Because I’m not interested,” I said.

Of all the emotions that ran through me, fear was not one of them. Having worked in construction throughout most of my high school years, I was very fit compared to the pudgy man in the other bed. He would not have dared to physically threaten me. If we came to blows, I could have—and would have—beaten him silly. What I did feel was surprise. And shock. And confusion. How did I end up here? Did I miss something in his manner that might have alerted me to what he really wanted from me?

He didn’t pester me any further. Did I get any sleep? I don’t recall. The next morning, he acted as if nothing had happened the night before. At the rally, he handed me a fistful of film rolls, I used them all, and at the end of the day I returned the rolls of exposed film to him and drove back to college. I was confident that I’d taken some really good photos.

Back at school, I waited for a check for my work to arrive in the mail. When it didn’t arrive after a few weeks, I called him. When he did not pick up, I left a message on his phone answering machine. A few more weeks passed and still no check arrived, so I called him again. This time he picked up.

“I’m not paying you because all of the photos you took are all black,” he said. “There’s nothing. You must have left the lens cap on.”

“That’s impossible,” I said. And he knew it was impossible. With an SLR (single-lens reflex) camera, which mine and his were, the viewfinder is through the lens so you can see exactly what you are photographing. If you have the lens cap on you see nothing. It’s like trying to see with your eyes closed.

“Then you must have overexposed all of the photos,” he said.

“That’s also impossible,” I said. He knew that, too. And we both knew he was lying.

I don’t recall what else we said. But I knew what was what: I’d been had. My photos were fine. He wasn’t going to pay me because I’d not climbed into bed with him that night in the Berkshires.

We never spoke again.

***

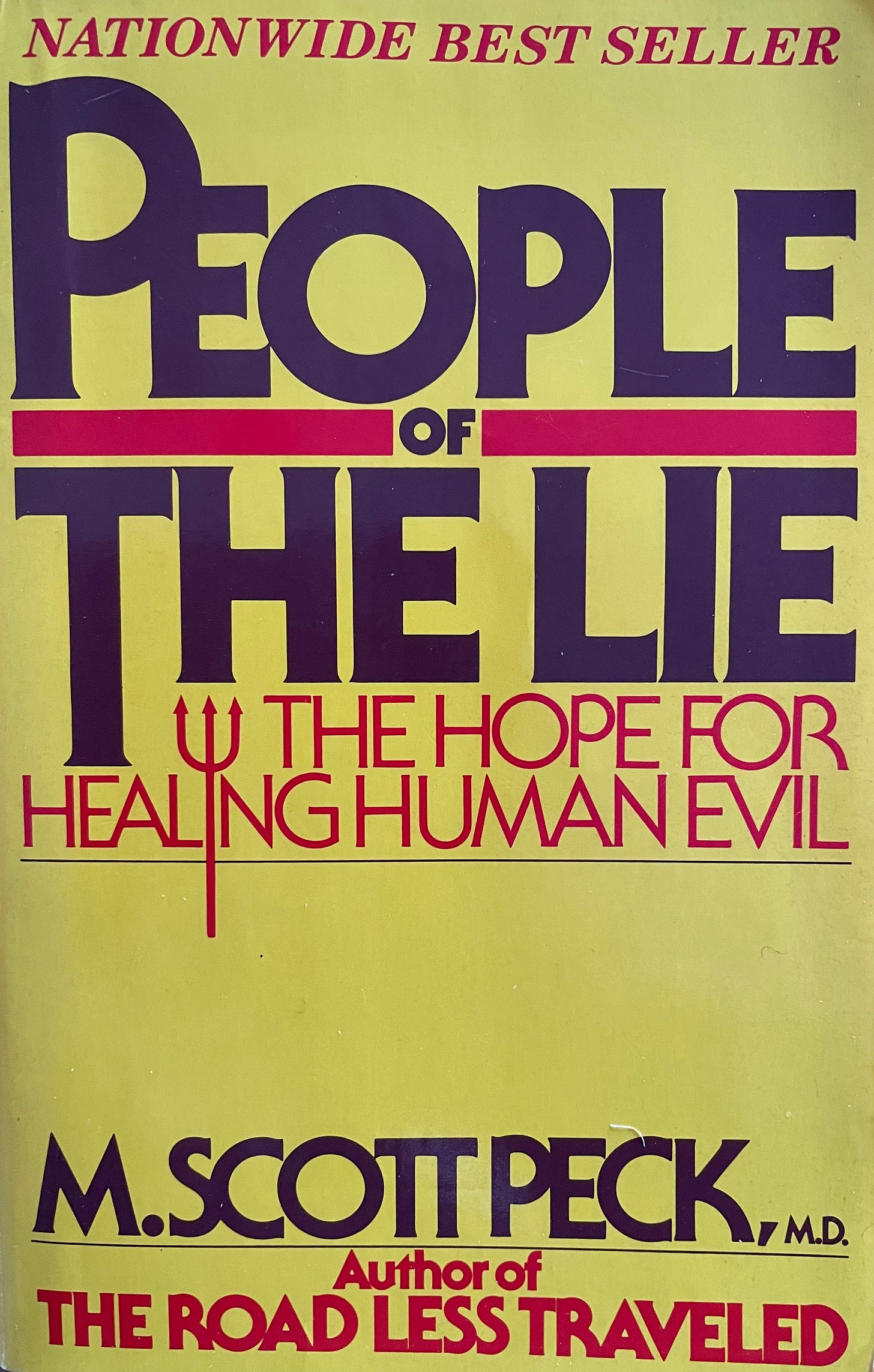

“This is a dangerous book,” M. Scott Peck begins People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil. “I have written it because I believe it is needed. I believe its over-all effect will be healing.”

I’ve had this book collecting dust on my shelf for many years. Recently, it caught my eye and I took it down, blew off the grime, and skimmed through its now-yellowing pages. It looked interesting. And in light of all the talk of “evil,” in the grip of which our nation appears to be, I decided to read it. I’m glad I did. I’d read his first book, the wildly popular The Road Less Traveled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth, many years after it was first published in 1978. At that time, I thought it was too way popular to be any good. But I’m glad I finally read that, too. It was transformative for me. These days we’d call it “a game changer.” I can say the same thing about People of the Lie.

The bulk of the book examines several cases that Peck supervised in his psychotherapeutic practice. In each case, he concluded that the patients were indeed evil. Or had been victims of evil people. In one such case, one of two sons (the older one was 16 years old) of a family had shot himself to death with his .22 caliber rifle. The parents had then regifted the rifle to the surviving son, Bobby, as a Christmas present. Bobby had told his parents he wanted a tennis racket. Peck first met the 15-year-old surviving son the day after he’d been admitted to a psychiatric hospital where Peck was in his first year of psychiatric training. Bobby had been behaving badly—"acting out,” is what we’d call it in today’s parlance—and he had been diagnosed with depression.

After months of consultation with Bobby and his parents, who seemed completely ignorant of the harm they had inflicted on their son with this “gift”—and then after the passage of 20 years to think and write about the case—Peck concludes: “I know now that Bobby’s parents were evil. I did not know it then. I felt their evil but had no name for it. My supervisors were not able to help me name what I was facing. The name did not exist in our professional vocabulary. As scientists rather than priests, we were not supposed to think in such terms.”

On evil people, he writes in People of the Lie:

“Utterly dedicated to preserving their image of perfection, they are unceasingly engaged in the effort to maintain the appearance of moral purity. They worry about this a great deal….

“While they seem to lack any motivation to be good, then intensely desire to appear good. Their ‘goodness’ is all on a level of pretense. It is, in effect, a lie. This is why they are the ‘people of the lie.’”

If The People of the Lie was needed, as Peck writes, when the book was published more than 40 years ago in 1983, then I believe it is needed even more now. For the book is not just about healing human evil; it is also about recognizing human evil and exposing it. This is what I want to focus on in this essay. This task is neither easy or rewarding. But it is important. As Peck writes, “We cannot begin to hope to heal human evil until we are able to look at it directly.” There is nothing more important that we can do now. Our survival—individually and collectively—depends on it. It is indeed a matter of life and death.

“Evil is in opposition to life,” Peck writes. “It is that which opposes the life force. It has, in short, to do with killing.” What’s more, he adds some pages later, is that “We brush up against evil not once or twice in a lifetime but almost routinely as we come in contact with human crises.”

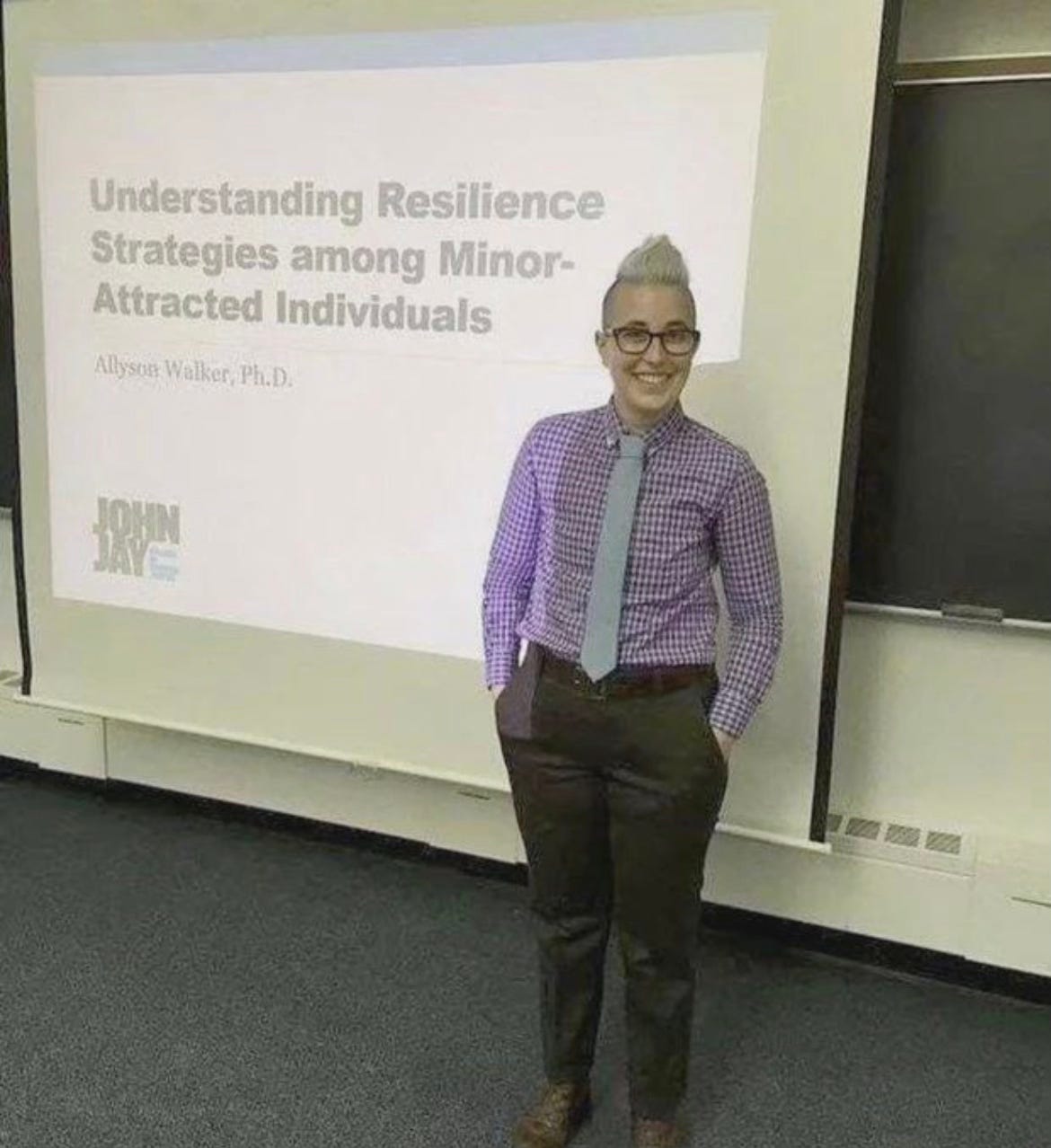

Indeed, I now see evil now more than I want to, making me wish there are things I did not know. I wish I did not know how our government has aided and abetted the millions of illegal immigrants crossing our nation’s southern border, packing our cities and suburban communities and schools and hotels and warehouses with them and their children in an effort to destroy our urban economies and educational systems and flood our country with deadly drugs and sex-trafficking; I wish I did not know that our government has aided and abetted boys and men to play in girl’s and women’s sports, aided and abetted boys and men to go into women’s locker rooms and bathrooms; I wish I did not know how our government has aided and abetted what’s being called “gender dysphoria,” standing by and watching young girls try to become boys and young boys try become girls; has aided and abetted sex-change surgeries (euphemistically called “gender-affirming surgery”) and the use of puberty blockers, thereby destroying the lives of young people who are beginning to regret their naïve choices but now have no way back to being the children they had been or to the adults they might have become; I wish I did not know that our government has aided and abetted institutionalized pedophilia (the perpetrators of which are now euphemistically called “minor-attracted individuals”); that our government has aided and abetted our mainstream media outlets and two of our most popular social media platforms—Facebook and Twitter—to not only censor important and lifesaving information that was critical about the COVID-19 jabs, but also to cover up the heinous Hunter Biden laptop scandal while daily diverting our nation’s short attention span by fomenting widespread hatred for Donald Trump and his supporters (talk about “hate speech”); that our government has sent untold billions of our tax dollars to fund the Ukraine military in a proxy war against Russia (which itself is evil), while millions of our own people are going hungry and are homeless and the middle class are racking up so much debt just to stay afloat that many Americans have more credit card debt than they have in savings.

***

Some people say that covidmania is over. It’s not over. The COVID-19 madness was the initial blow that got us all reeling, like a whack on the head. That was the whole point. And that has not stopped. If anything, the confusion has become even more rampant. This is happening because one of the main motives of evil is to create confusion. “Lies confuse,” Peck writes. “The evil are ‘the people of the lie,’ deceiving others as they also build layer upon layer of self-deception.”

I remember being confused that night years ago in that motel room with the photographer. What was he expecting me to do? Did I do anything to lead him on? I even wondered if, after all, I should have left the room and gotten one on my own. Or just gotten up and gone back to school. Was he an evil man? I think he was. Not because he wanted me to climb into bed with him. What was evil was that he refused to pay me for my work because of it. It was as if I’d snubbed him. It was as if I’d led him on then let him down. But I did nothing of the sort. He’d made a wild proposition completely out of the blue and I turned it down, which I had every right to do. Evil is not just evident in the most heinous and obvious acts of human depravity. It’s all around us for those of us with eyes to see it, and we see it sometimes only in hindsight—if at all, leaving us feeling haunted by some unnameable presence in our lives.

I can see now that where the evil lay in that incident with the photographer is not only in not paying me; it was also in the pretense of him helping me develop a gig in motorcycle racing photography, which I enjoyed and in which I was becoming quite adept. In fact, he was the one who’d led me on. His pretense of helping me was a lie. It was all appearances. Peck writes: “The words ‘image,’ ‘appearance,’ and ‘outwardly’ are crucial to understanding the morality of evil…. Their ‘goodness’ is all on a level of pretense. It is, in effect, a lie.” And so it was with this photographer. He was pretending to help me. But it was a lie. He wanted something else from me. And that pretending was evil. It was also evil because he was, in effect, blaming me for rejecting his offer. What did not happen in his bed that night was somehow my fault. I’d been made his fall guy, a scapegoat. And scapegoating, Peck writes, is another predominant characteristic of evil people.

***

It is no accident that so much evil has come upon us at a time when Americans have become less religious than at any other time in our nation’s history. As most Americans just celebrated Christmas, the percentage of adults who report regularly attending religious services remains at an all-time low. A recent Pew Research Center survey finds that 80 percent of U.S. adults say religion’s role in American life is shrinking—a percentage that’s as high as it’s ever been in the research center’s surveys.

If nature abhors a vacuum, so does the human soul. Our souls inherently long to be connected to something larger and more universal than our individual selves. Peck, who spent many years “of vague identification with Buddhist and Islamic mysticism” made a “firm Christian commitment” and was baptized in 1980 at the age of 43, has this to say: “There are only two states of being: submission to God and goodness or the refusal to submit to anything beyond one’s own will—which refusal automatically enslaves one to the forces of evil. We must ultimately belong to either God or the devil…. As C.S. Lewis put it, ‘There is no neutral ground in the universe: every square inch, every split second is claimed by God and counterclaimed by Satan.’”

In his book, Peck cites another book on evil and demonic possession, Malachi Martin’s terrifying 1976 Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Contemporary Americans. In an updated preface for the 1992 reprint of the book, Martin offers a lucid and articulate account of how America had fallen prey to evil. He writes:

“That a more favorable climate exists now than ever before for the occurrence of demonic Possession among the general population is so clear, that it is attested to daily by competent social and psychological experts, who for the most part appear to have no ‘religious bias.’

“Our cultural desolation—a kind of agony of aimlessness coupled with a dominant self-interest—is documented for us in the disintegration of our families. In the breakup of our educational system. In the disappearance of publicly accepted norms of decency in language, dress and behavior. In the lives of our youth, everywhere deformed by stunning violence and sudden death; by teenage pregnancy; by drug and alcohol addiction; by disease; by suicide; by fear. America is arguably now the most violent of the so-called developed nations of the world.”

More recently, Jonathan Cahn writes in his 2022 book, The Return of the Gods:

“Even many secular observers and those of no faith have noted that it seems as if something has come to possess American and Western culture; something has taken it over. But we should not be surprised at what is happening. The mystery ordains it. A house that has emptied itself of God cannot remain empty. It will be seized and taken over by that which is not God. And when a civilization expels God from its midst, it never ends well….

“It is a basic tendency of human nature not to realize what one has until one no longer has it. Rarely do we discern the danger from which we are being protected until the protection is removed. When the light is removed, its absence will always be occupied by darkness. And when God is removed, His absence will be occupied by evil.”

Ana Maria Mihalcea, author of Light Medicine - A New Paradigm: The Science of Light, Spirit and Longevity, recently wrote in her popular Substack column:

“Most people are completely lost in this world that is so filled with noise, social indoctrination, limiting beliefs, social programming on who people should be in the eyes of society. This is the most dangerous mind disease of our times, as you were able to see in the COVID19 era, where following others could even lead you to accept a bioweapon of mass destruction under the guise of a vaccine. Deception is everywhere in these times.”

***

Peck draws a line between people who are evil and people who are genuinely possessed by demons. Although, he writes, “…I do believe there is some relationship between Satanic activity and human evil.” But the possessed are, so to speak, an entirely different animal. Peck writes:

“Five years ago when I began to work on this book I could no longer avoid the issue of the demonic…. Having come over the years to a belief in the reality of a benign spirit, or God, and a belief in the reality of human evil, I was left facing an obvious intellectual question: Is there such a thing as evil spirit? Namely, the devil?

“I thought not. In common with 99 percent of psychiatrists and the majority of clergy, I did not think the devil existed. Still, priding myself on being an open-minded scientist, I felt I had to examine the evidence that might challenge my inclination in the matter. It occurred to me that if I could see one good old-fashioned case of possession I might change my mind.”

So that’s what he set out to do. And he did not witness just one case of possession; he saw four. The first two cases, he writes, “turned out to be suffering from standard psychiatric disorders.” The third case, he writes, “turned out to be the real thing.” Then he got involved in a fourth case. After these latter two cases, he was able to offer this conclusion: “I now know that Satan is real. I have met it.”

Peck does not describe either of these cases but instead refers to Martin’s book, Hostage to the Devil, which describes five cases of possession. Peck writes: “All of my experience confirms the accuracy and depth of understanding of Martin’s work, and a case description of my own would contribute practically nothing beyond his writings.”

Peck does, however, elaborate on how one becomes a victim of possession. He writes:

“Possession appears to be a gradual process in which the possessed person repeatedly sells out for one reason or another. The primary reason both these patients sold out seemed to be loneliness. Each was terribly lonely, and each, early in the process, adopted the demonic as a kind of imaginary companion….

“They were not only lonely people, but were accustomed to being lonely, and when they came to exorcism each was still basically a loner.”

Both Peck and Martin concur that possession begins as an individual choice. To Peck, the possessed person “repeatedly sells out.” Martin writes: “At some point during this earliest stage there arrives a delicate moment when each person chooses to consider the particular offer made to him or her.” Of the people described in the five cases that Martin depicts in his book, each agreed that they had made such a choice, “and that they had a sense of violating their consciences when they made it, though at the time in some cases it seemed a fairly minor violation.” Although the consent of the victim is required for possession, the diabolic attacks make it hard to resist. The aim, Martin writes, is to “frighten them, subdue them, fascinate them, to act upon their senses and imagination in order finally to elicit their consent.”

Reading all of this, I cannot help but think of the government’s relentless campaign to get people to consent to being injected with the so-called COVID-19 vaccine, knowing—as our federal agencies and Pfizer knew from the very start jab rollout—that the jabs were designed to maim and kill us, and to destroy humanity’s reproductive capacities. Given this scenario and evidence, I cannot help but think that our government, and many other governments around the world, are indeed demonic. And that those who chose to get the jabs out of fear—and zealously demanded others get jabbed—became in some way possessed. This might explain why it’s been so impossible to get through to them with the truth of what’s happening to all of us. It’s almost as if nothing short of exorcism will save them from themselves. It’s that mighty pretense in each of them that stands like an impenetrable fortress guarding the lies that, if broken through, would collapse into some sort of calamity. Which I’m beginning to think is what needs to happen if we are to individually and collectively survive this hostile takeover of our very being.

Consider this observation from Peck:

“Satan cannot do evil except through a human body…. [I]t cannot murder except with human hands. It does not have the power to kill or even harm by itself. It must use human beings to do its delivery. Although it repeatedly threatened to kill the possessed and the exorcists, its threats were empty. Satan’s threats are always empty. They are all lies.”

Governments around the world said the jabs were safe. It was a lie.

Governments around the world said the jabs would stop the spread of the virus and reduce the chances of someone who contracted COVID-19 from requiring hospitalization. It was a lie.

Governments around the world said anyone of any age could die from COVID-19. It was a lie.

Governments around the world said masks would help reduce the spread of the virus. It was a lie.

Governments around the world said that isolation and social distancing would stop the spread of the virus. It was a lie.

Governments around the world said it was necessary to shut down stores, restaurants, schools, parks, beaches, churches, and all civic and community events to stop the spread of this deadly virus. It was a lie.

Governments around the world said the unvaccinated spread the virus and that they would all die from COVID-19. It was a lie.

Peck writes:

“As well as being the Father of Lies, Satan may be said to be a spirit of mental illness. In The Road Less Traveled I defined mental health as ‘an ongoing process of dedication to reality at all costs.’ Satan is utterly dedicated to opposing that process. In fact, the best definition I have for Satan is that it is a real spirit of unreality. The paradoxical reality of this spirit must be recognized. Although intangible and immaterial, it has a personality, a true being. We must not fall back into Saint Augustine’s now discarded doctrine of the ‘privatio boni,’ whereby evil was defined as the absence of good. Satan’s personality cannot be characterized simply by an absence, a nothingness. It is true that there is an absence of love in its personality. It is also true, however, that pervading this personality is an active presence of hate. Satan wants to destroy us. It is important that we understand this.”

***

Peck closes his book with a recollection and insightful reflection upon the My Lai incident of the Vietnam War. He uses this example to illustrate the phenomenon of group evil. By way of background, Peck writes: “On the morning of March 16, 1968, elements of Task Force Barker moved into a small group of hamlets known collectively as MyLai in the Quang Ngai province of South Vietnam. It was intended to be a typical ‘search and destroy mission’—that is, the American troops were searching for Vietcong soldiers so as to destroy them.”

Peck goes on to report that what happened at the outset of the killing spree remains unclear. “What is clear, however,” he writes, “is that the troops of C Company killed at least somewhere between five and six hundred of those unarmed villagers… The most large-scale killings occurred in the particular hamlet of MyLai 4. There the first platoon of Charlie Company, under the command of Lieutenant William L. Calley, Jr., herded villagers into groups of twenty to forty or more, who were then slaughtered by rifle fire, machine gun fire, or grenades.”

While the mass murder was unfolding, only one person tried to stop it: a helicopter pilot flying in to support the mission. Peck writes: “Even from the air he could see what was happening. He landed on the ground and attempted to talk to the troops, to no avail. Back in the air again, he radioed to headquarters and superior officers, who seemed unconcerned. So he gave up and went about his business.”

As it turned out, both the killings and the cover-up were a massive group lie on the part of the soldiers on the ground who were responsible for the killings and of those all the way up the chain of command to the President of the United States, which was Lyndon Johnson at the time. And lying, as Peck writes, is “simultaneously one of the symptoms and one of the causes of evil.” They were all “people of the lie,” Peck writes. But it does not stop there. He proffers the idea that “the American people, at least during those war years, were also people of the lie.”

The My Lai debacle, and indeed the entire Vietnam War, Peck writes, was the result of group fear, narcissism, and laziness. Fear that somehow South Vietnam was another domino that would fall toward a communist takeover of the world; narcissism or “enemy creation” and “group pride” that America had the right to intervene in what was really an attempt for Vietnam to regain its sovereignty from decades of colonial rule; and laziness because most Americans, Peck believes, did not know why—or want to know why—America was even involved in the war. “We were so wrong because we never seriously considered that we might not be right,” Peck writes. He continues:

“As an example of group evil MyLai was not in inexplicable ‘accident’ or unpredictable aberration. It occurred in the context of a war, which is itself an evil context. The atrocities were committed by the side that was the aggressor and that, in its aggression, had already fallen into evil. The evil of the small group—Task Force Barker—was clearly a reflection of the evil of the whole American military presence in Vietnam. And our military presence in Vietnam was directed by a deceitful, narcissistic government that had lost its bearings and that was mandated by a nation that had fallen into torpor and arrogance. The entire atmosphere was rotten. The massacre at MyLai was an event waiting to happen.”

What strikes me the most about Peck’s conclusion about why and how the Vietnam War was allowed to happen is something that is as apropos today as it was then, and will be as long as humans exist. He writes:

“A single vote may be crucial in an election, so the whole course of human history may depend on a change of heart in one solitary and even humble individual. This is known to the genuinely religious. It is for this reason that no possible activity is considered to be more important than the salvation of a single human soul. This is why the individual is sacred. For it is in the solitary mind and soul of the individual that the battle between good and evil is waged and ultimately won or lost.”

I think back on the covidmania group-think (group evil) of the vaxx pushers in the government, mainstream media, the medical profession, as well as ordinary people all over the world demonizing individuals such as myself for refusing to comply with this massive crime against humanity and not get injected with a bioweapon. My individual choice—"my body, my choice”, as feminists like to proclaim—and the individual choice of others who also had the good sense not to comply, was considered some sort of selfish and rogue position while I was, and many others were, standing up for the sacred right of individuals all around the world. Peck writes:

“Whether we affect history for good or for ill is, of course, each individual’s choice. One fine means of teaching us our potential individual responsibility for group evil and history occurs in certain churches on Good Friday when, in reenacting the Passion according to Saint Mark, the congregation is required to play the role of the mob and to cry out ‘Crucify him.’”

***

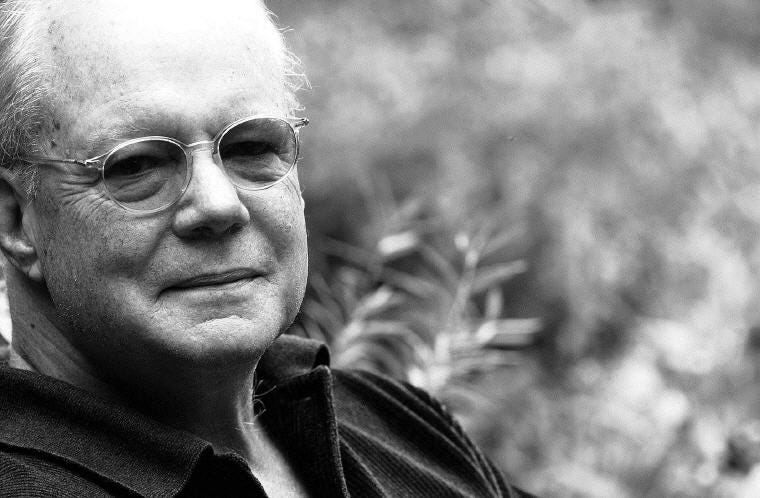

Morgan Scott Peck was born on May 22, 1936, in New York City, the son of Zabeth (née Saville) and David Warner Peck, an attorney and judge. His parents were Quakers. Peck was raised a Protestant. The younger of the couple’s two sons, Peck was 13 when his parents sent him to the prestigious boarding school Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire. He hated it. At age 15, during the spring holiday of his third year, he came home and refused to return to the school. His parents sought psychiatric help for him and he was diagnosed with depression and spent five weeks in a psychiatric hospital. He then transferred to Friends Seminary in 1952 and graduated in 1954, after which he received a BA from Harvard in 1958, and an MD degree from Case Western Reserve University in 1963. He served in the U. S. Army, rising to lieutenant colonel, first as chief of psychology at the U.S. Army Medical Center in Okinawa and later as assistant chief of psychiatry and neurology in the Office of the Surgeon General in Washington.

He earned the moniker of “the nation’s shrink” after the publication of his first book, The Road Less Traveled, in 1978. Although he would go on to publish a total of 15 books, the second of which was People of the Lie, it is The Road Less Traveled that remains the best known of his works. It has sold more than 10 million copies in over 20 language translations. Both The Road Less Traveled and People of the Lie still have remarkably high sales rankings on Amazon.

Random House, where the little-known psychiatrist first tried to peddle his original manuscript, turned him down, saying the final section was “too Christ-y.” Simon & Schuster bought the work for $7,500 and printed a modest hardback run of 5,000 copies. The book took off only after Peck hit the lecture circuit and personally sought reviews in key publications. Reprinted in paperback in 1980, The Road Less Traveled first made bestseller lists in 1983, five years after its initial publication. Much of the book’s popularity was on account of it having been widely endorsed by Catholic and Protestant church officials and self-help groups, including Alcoholics Anonymous. The earnings from The Road Less Traveled and his other books, would make Peck a multi-millionaire.

Because he was a psychiatrist, Peck made self-help respectable for a wide-ranging audience. Yet, his own life was a mess. Although Peck wrote eloquently about love, marital fidelity, and self-discipline, he had multiple infidelities during his 40-year marriage to Lily Ho Peck, with whom he had three children. Lily Ho Peck filed for divorce in 2003, and the next year he married Kathleen Kline Yeates. He wrote about much of this in his 1995 book, In Search of Stones: A Pilgrimage of Faith, Reason, and Discovery.

Arthur Jones in his 2007 biography of Peck, The Road He Traveled: The Revealing Biography of M. Scott Peck, writes: “He lived as if admitting a wrong or a fault of itself brought forgiveness, that the admission obviated the need to express remorse, make amends and seek a genuine reconciliation.” On his website about a 2015 revised and retitled version of his biography on Peck, called, Boomer Guru: How M. Scott Peck Guided Millions but Lost Himself on The Road Less Traveled, Jones calls him a “classic wounded healer.” In other words, he’d experienced the same problems he helped his patients with.

Peck’s life did not end well. In his last years, Peck suffered from Parkinson’s Disease. He died on September 25, 2005 of pancreatic and liver duct cancer at his home in Warren, Connecticut. He was 69.

In Boomer Guru, Jones writes:

“He was the Boomers’ guide out of their personal and social wilderness. He provided a psychotherapeutic commonsense that unlocked their psychological blocks—it was commonsense with a spiritual lodestone. He searched for God; he was seeking God for himself and for others. He wrote, prayed, meditated, and preached a God in whom he desperately wanted to believe…. Over a quarter-century, thousands attended his talks and workshops, work that continued into the 1990s. Yet a decade later, scarcely a hundred people were present at his 2005 memorial service, and six weeks earlier only two of three children had shown up for his private family-and-friends funeral.”

“The man once known as ‘the Nation’s Shrink,’ had shrunk into oblivion…. The man who’d blended psychiatry and religion, who’d spoken comfortingly of God’s love and one’s own death, at his own end, when gripped by Parkinson’s Disease and dying of pancreatic cancer, never mentioned God at all.

“Was it all a hoax? No. It was a tragedy.”

Whatever his personal failings may have been, Peck and his People of the Lie contributed an invaluable voice to the many others who have warned us of evil that has dogged humanity for eons. And for that, I, for one, am grateful. And it is up to us to carry on exposing evil where it lives, and to continue to learn about it. We ourselves can say with Peck when he writes: “I have not learned about human evil; I am learning. In fact, I am just beginning to learn.”

Selected Bibliography

Cahn, Jonathan. The Return of the Gods. Lake Mary, Florida. FrontLine, 2022.

Jones, Arthur. Boomer Guru: How M. Scott Peck Guided Millions but Lost Himself on The Road Less Traveled. Capparoe Books, 2015.

Martin, Malachi. Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Contemporary Americans. New York, N.Y. HarperOne, 1992. First published by HarperCollins Publishers in 1976.

Peck, M. Scott. People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil. New York, N.Y. Simon & Schuster, 1983.

Peck, M. Scott. The Road Less Traveled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth. New York, N.Y. Simon & Schuster, 1978.

This is the fifth edition of Underlined Sentences. If you missed any of the four previous editions, you can read them here, here, here, and here.

My goal with this column is to offer thoroughly researched, informative, and insightful observations on the “underlined sentences” of both timely and timeless books or other written documents that I feature. I offer a brief sketch of the writers and place their texts—books, essays, poems, scripture—in the context in which they were written.

I also explore how they are relevant to our lives today. And I reflect on how they have challenged me to think about my life and how I can tap into their wisdom to get to the heart of the difficult matters that increasingly plague us, and to help guide us through them, if only by holding each other in an emotional and intellectual embrace. These columns take a considerable amount of time to research and write, so I’m posting them once every few weeks.

My four previous columns featured writers of the WWII and post-war era. They warned us about the dangers of Marxism looming then in Europe and here in America, a threat which continues today on both sides of the Atlantic. With People of the Lie, I have shifted my focus to the 1980s as much of Western Civilization began to awaken and to wrestle anew with the forces of evil.

Please comment, share, and subscribe (see link below). Subscriptions are free, although there is a paying option. Or you can make a one-time contribution by clicking on the “Buy me a coffee” button below for other options. And, as always, thank you for reading. I would love to hear from you. If you’d like to contact me, email me: jimkullander@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment