Will reopening what now appears to be the deliberately covered-up murder of Secretary James Forrestal implicate the CIA?

[This article continues CAM’s series on political assassinations.—Editors]

“He was brought before his time

David Martin, “Forrestal’s Resting Place in History.”

To Arlington to reside.

Now, at last, the truth is known:

It wasn’t from suicide.”

On May 22, 1949, just before 2:00 a.m., America’s first Defense Secretary James Forrestal plunged to his death from a 16th floor window in the main tower of the Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland.

Forrestal had been admitted to the hospital against his will, diagnosed as suffering from “operational fatigue,” and kept in confinement in a room with security-screened windows for seven weeks while being treated with insulin-induced shock therapy and barbiturates.[1]

One of his visitors was then-Congressman Lyndon B. Johnson, who managed to gain entrance to his suite “against Forrestal’s wishes.”[2]

The New York Times reported Forrestal’s death as a suicide, though the belt, or sash, of his dressing gown was tied tightly around his neck—indicating murder.[3]

The Official Version of Forrestal’s Death

According to the official version of history—promoted by Forrestal biographers Townsend Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley—Forrestal had been admitted to the Bethesda Naval Hospital after experiencing a mental breakdown under the stresses of the early Cold War and his job.

Columnist Drew Pearson reported that Forrestal was found in the middle of the night in his pajamas on the street shouting “The Russians are coming, the Russians are coming.”

On the night of Forrestal’s death, the Navy Corpsman assigned to keep watch on him until midnight, Edward W. Prise, had observed him pacing the floor and had grown worried. Forrestal had told the corpsman that he did not want to take the usual prescribed sedative because he planned to stay up and read.

The corpsman had tried to alert the doctor on duty, sleeping in his room next to Forrestal, that something was wrong with Forrestal’s emotional state, but the doctor brushed him off and went to bed.

At 1:45 a.m., the new corpsman, Robert Wayne Harrison, Jr., looked into Forrestal’s room and allegedly saw him copying a poem.

The poem turned out to be from Mark Van Doren’s Anthology of Poetry, Sophocles’ “The Chorus from Ajax,” in which Ajax in a forlorn state contemplates suicide.

Forrestal supposedly copied key lines from the poem ending with the word Nightingale.

Author John Loftus speculated that Forrestal was overwhelmed with feelings of guilt for having authorized a CIA operation with the code name of Nightingale that infiltrated expatriate spies into the Soviet Union, many of whom were former Nazi collaborators guilty of horrible atrocities against Jews.

After finishing writing the poem, Forrestal—according to the official story—walked out of the room to the kitchen across the hall, tied the sash from his dressing gown to the radiator beneath the window and tried to hang himself outside the window.

When the sash gave way, he fell 13 floors to the 3rd floor roof of a hallway below, dying instantly.

The corpsman allegedly was not there to prevent it because Forrestal had ordered him on an errand to get him out of the way.

According to biographers Hoopes and Brinkley, no one knows whether Forrestal jumped or hung until the silk sash gave way, but “scratches found on the cement work just below the window suggest that Forrestal may have hung for at least one terrible moment, then changed his mind—too late—before the sash gave way.”[4]

Suicide or Murder?

Admiral Leslie Stone, the Bethesda hospital commandant, Dr. George N. Raines, the Navy psychiatrist in charge of the case, and Dr. Frank Boschart, a Montgomery County, Maryland, coroner, publicly called Forrestal’s death a suicide—in violation of the basic investigative rule of police that all violent deaths should be treated as a murder until sufficient evidence is gathered to prove otherwise.[5]

Forrestal was never actually suicidal. Many people who spent a lot of time with him—including his chauffeur, John Spalding, and replacement as Defense Secretary Louis Johnson—found him in good spirits and acting normally.[6]

Dr. Raines himself had said that Forrestal at the time of his death was “better” than in preceding weeks and “nearing the end of his illness,” adding that “at no time during his residence” had he “made a suicidal gesture or a suicidal attempt.”

Forrestal’s nurse, the last person to see him alive, reported his mood to be “bright, polished and even slightly flirtatious.”[7]

Because of the suicide labeling, there was never any autopsy report. Crime scene photographs turned up missing, pointing to a police cover-up.[8]

Both attendant Harrison and on-call Dr. Robert R. Deen were negligently slow in reporting Forrestal’s disappearance from his room and were transferred from the Bethesda Naval Hospital soon after Forrestal’s death.[9]

Somehow, they did not see or hear him walk across the corridor from his room to the kitchen, tie his bathrobe to the radiator around his neck, unfasten the window screen, climb over the window and plunge to his death.[10]

If Forrestal were truly intent on suicide, he would have almost certainly jumped out the window rather than tying his bathrobe to a radiator and hanging himself outdoors.

As a Navy veteran, Forrestal also would not have been so incompetent to have tied a knot that came undone.[11]

There is no actual evidence, furthermore, to indicate that Forrestal’s bathroom cord had ever been tied to the radiator—which, according to investigator Cornell Simpson, would have been the most “improbable gallows imaginable.”[12]

The cord tied around Forrestal’s neck was more likely used as a weapon by his assailant—possibly a phony patient on Forrestal’s floor—to throttle him before throwing him out the window.

This would have been consistent with the CIA’s assassination manual—written in the early 1950s—which stated that “the most efficient accident, in simple assassination, is a fall of 75 feet or more onto a hard surface.”[13]

“The Jews or Communists Did My Brother in”—Henry Forrestal

James’s brother Henry Forrestal—a successful businessman who resided in the family home in Beacon, New York—felt certain from the beginning that James had not killed himself, and though a Democrat, blamed the Truman administration for covering up his brother’s murder.

Henry said that James was “the last person who would have committed suicide, had absolutely no reason for taking his life” and that “the whole affair smelled to high heaven.”[14]

A few days before James’s death, Henry had visited him and, later, told researcher Cornell Simpson that he had found James “acting and talking as sanely and intelligently as any man I’ve ever known.”[15]

The timing of his brother’s death was suspicious because Henry was coming to take him out of the hospital a few hours later that day and he was slated for discharge soon thereafter. Staff had described James as being “ebullient and meticulously shaven” as he “ate steak for lunch, eager to meet his son Peter.”

A suicide note was never found—and James was a prolific writer who had just completed a three-volume analysis of America’s foreign relations for the guidance of the president and the National Security Council.[16]

At the time, James was very well set-up financially, in good health and had expressed interest to powerful Wall Street friends about starting a newspaper or magazine modeled after The Economist of Great Britain, which they were willing to help finance.[17]

He was also planning to publish memoirs based on a detailed diary he had kept about his years in the government, which might have been explosive.[18]

Henry suggested that either “the communists” or “the Jews” did his brother in, with the help of the Truman government.[19]

While many would object to the insinuations behind these claims, Henry’s odious political views do not diminish the legitimate basis for his suspicions that his brother was murdered.

Henry said that, after his brother’s death, James’ good friend Monsignor Maurice Sheehy, a Navy chaplain, had hurried to the hospital to learn about the circumstances of Forrestal’s death and was approached by a stranger in the crowded hospital corridor.

The man was a hospital corpsman and warrant officer wearing stripes attesting to 20 years of service in the Navy. He said to Monsignor Sheehy in a low tense voice: ‘Father, you know, Mr. Forrestal didn’t kill himself, don’t you.”[20]

The Wilcutts Report

The official story about Forrestal’s “suicide” has been repeated consistently for decades, including by Forrestal biographers Hoopes and Brinkley.

However, it is contradicted by evidence provided in a five-day military investigation that was convened on May 23, 1949, by Morton D. Willcutts, Rear Admiral of the Navy’s Medical Corps, with Captain A.A. Marsteller as a senior ranking officer.

The Wilcutts report was approved on July 13, 1949, but the Navy never published it and it remained filed away and forgotten until April 2004 when researcher David Martin discovered it using a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.[21]

Though the report affirmed the view of suicide, the most significant testimony came from Nurse Dorothy Turner who saw Forrestal’s room minutes after his death, around 1:48 a.m. She described seeing slippers and a dry razor blade on the floor and shards of broken glass on the bed, whose sheets were turned over.[22]

A photograph of the room taken after Forrestal’s death showed broken glass—which came from an ashtray that had been near Forrestal’s bed—on the rug.

This indicated a struggle, and that someone had tampered with the crime scene.

Afterwards, the room was cleaned. Photos taken early the next day showed a bed with nothing but a bare mattress and pillow on it, which was different from what Nurse Turner observed.[23]

The cleaners, however, seemed to have overlooked the clear pieces of glass two feet or so from the foot of the bed.[24]

Immediately after Forrestal’s death, Nurse Turner, who was in charge of the 16th floor, was transferred to Guam, far out of the reach of most reporters.[25]

Forrestal’s chauffeur, John Spalding—who said that Forrestal had never appeared depressed, paranoid or in any way abnormal in his presence—was transferred to Guantanamo Bay after being made to sign a statement by a Navy Rear Admiral that he would never speak to anyone again about Forrestal.[26]

Sophocles Poem Mystery

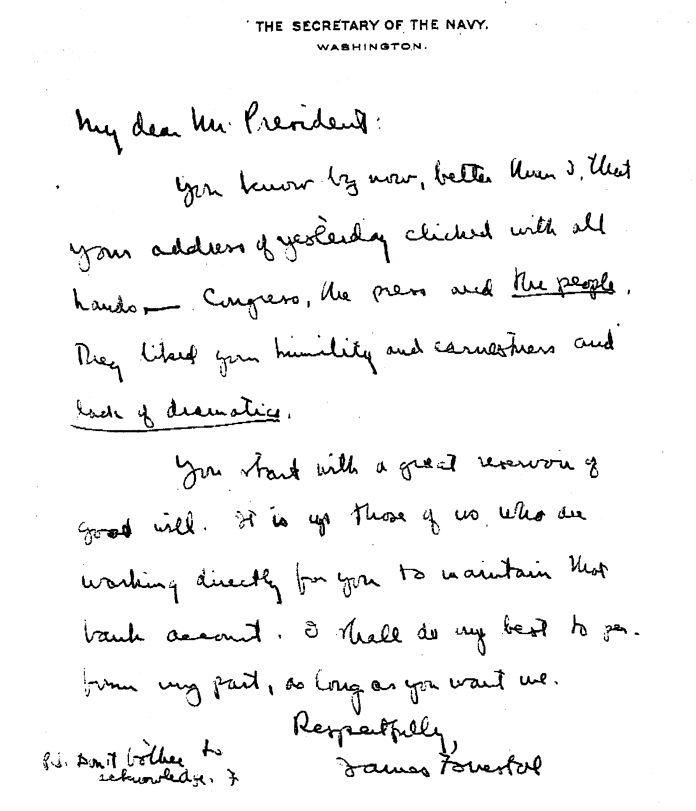

In December 2007, The Hyattsville Times compared the transcribed Sophocles poem with a letter Forrestal had written to President Harry Truman.

It was evident for everyone to see that the Sophocles poem was not in Forrestal’s handwriting—so it could not have been his transcription.

The whole story was obviously fabricated and evidence manufactured to provide a diversion away from the absence of a suicide note from a distinguished statesman and prolific writer.

The time element makes it impossible for Forrestal to have copied the poem as, according to the hospital’s story, Forrestal was asleep at 1:30 a.m., was seen awake at 1:45 and then was missing by 1:50.

Thus, Forrestal would have had to awaken from a sound sleep, read and copy 17 lines of the poem and then cross the hall into the kitchen and hang himself in less than 15 minutes.[27]

None of the newspapers at the time actually reported that Forrestal’s Navy Guard hospital apprentice, Robert Wayne Harrison, saw him copying the poem, and the Willcutts Report makes no mention of any poem or book of poetry or witnesses who came across the poem.

Harrison, who came on duty at 11:45 a.m. on the night of the killing said that Forrestal was in his bed sleeping and did not do any reading—let alone transcribing any poems.[28]

Also of note, the Anthology was reported to have been opened to page 279 where the poem was “Chorus from Alcestis”—and not Sophocles’ “The Chorus from Ajax.”

The lines that Forrestal copied were also less applicable to a case of suicide than lines near the end of the chorus which captured the poet’s thoughts on the desirability of dying.[29]

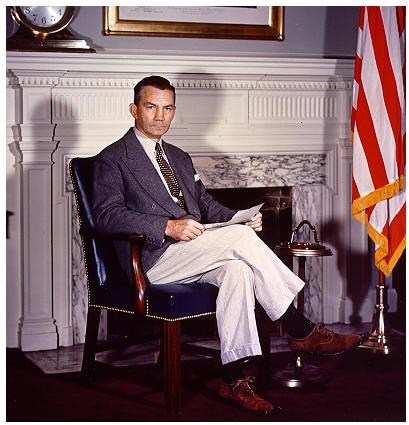

Who Was James Forrestal?

Forrestal’s name lives on today in the first U.S. Supercarrier, the USS Forrestal, and in a military office nicknamed “Little Pentagon” which now houses the U.S. Department of Energy.

These honors reflect Forrestal’s commitment to huge naval buildups and the opening of the Middle East to U.S. oil interests.

Forrestal was a key architect of the “American Century” who promoted an aggressive anticommunist foreign policy that made him a hero to the right-wing John Birch Society.

It is one of history’s great ironies that he shared the same fate of so many other victims of an empire for which he was “present at the creation.”

James Forrestal was born in Matteawan, New York, on the Hudson River in 1892. His father James was a loyal Democrat who was appointed Matteawan postmaster by Grover Cleveland.

James Jr.’s most striking physical feature was a broken nose that he sustained in amateur boxing.

After attending Princeton University and dabbling in journalism, he embarked on a lucrative investment banking career with William A. Read & Company (later Dillon, Read & Co.) of which he became president by 1937.[30]

This latter position owed in part to his success in coordinating the merger of Standard Oil of California and Texaco (to form Caltex) with the help of Dillon, Read Vice President Paul Nitze, who went on to draft the NSC-68 document that advocated for aggressive policies in the Cold War.[31]

Approving controversial loans to the industrial heartland of Germany after World War I that enabled Hitler’s rearmament, Forrestal sat on the board of the American subsidiary of I.G. Farben, which manufactured the Zyklon B gas that was used to exterminate the Jews (and others) in the concentration camps.[32]

Described by The New York Times as a “quiet, articulate individual who disliked publicity,” Forrestal had grown up attending military parades in Matteawan and was a fervent supporter of the Spanish-American War—his office wall held maps with the positions of U.S. and Spanish forces.[33]

After a stint in the New York National Guard and Navy during World War I, he was tapped in 1940 as an administrative assistant to Franklin D. Roosevelt—his former neighbor whom he had helped elect to the State Senate in 1910 as a staffer with the Dutchess County Democratic Party.

Forrestal was subsequently appointed as Under Secretary of the Navy and served as Secretary of the Navy from 1944 to 1947, during which time he presided over a major naval buildup.[34]

According to biographers Hoopes and Brinkley, Forrestal was the “brilliant, tireless administrator without whose masterly contribution the navy mobilization program in World War II—which saw the fleet inventory grow from 1,099 to 50,759 vessels and its rank of officers and sailors increase from 160,997 to 3,383,196—could not have been completed.”[35]

Toward the end of the war, Forrestal pushed for a lenient policy toward Japan as a means of ending the bloodshed and blocking Soviet penetration into the Far East, and helped develop the policy by which the U.S. allowed them to keep the Emperor while placating the American public by fashioning the surrender terms as “unconditional.”[36]

Forrestal at the same time advocated for the U.S. annexation of Micronesia, the Bonins, the Volcanoes, and Marcus Island, which he believed could be used as a “far-reaching, mutually supporting base network” from which large-scale offensives could be launched.

Forrestal told Congress that American security in the post-war Pacific depended upon the United States forming a “defensive wedge” in the Asia-Pacific based on “positions in the Aleutians, the Ryukyus, and Micronesia and defended by mobile sea power.”[37]

After the war, Forrestal lobbied in Washington against the recommendation of George C. Marshall to cut off aid to anti-communist warlord Chiang Kai-Shek, whom the U.S. had supported against the Maoists in China’s civil war.

At a Cabinet meeting on November 26, 1948, Forrestal urged that the “Flying Tigers”—pilots contracted under a private airline who assisted Chiang against the Japanese in World War II—be reactivated, and subsequently set up his own private intelligence network, hiring loyal Chinese agents at Chiang’s new headquarters in Formosa to infiltrate and mount sabotage operations against Communist China.[38]

Forrestal’s zealous anti-communism—predicated on the belief that the Marxian dialect was as incompatible with democracy as was Nazism or Fascism—inspired Senator Joseph McCarthy. Forrestal told McCarthy of people in the government he believed were Soviet agents.[39]

Townsend Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley called Forrestal the “godfather of Containment.” George F. Kennan, the State Department expert who developed the containment strategy, stated that Forrestal was “one of the first senior figures in our government to realize that Stalin and the men around him were brutal and high-stepping gangsters with much blood on their hands who could not be appealed to by personal charm (as FDR fancied he could do).”[40]

Privately, Forrestal raised close to $1 million to prevent a communist victory in the 1948 elections in Italy.[41] The conciliatory Yalta agreement in 1945 was to him a “sellout,” and the Morgenthau Plan for the deindustrialization of Germany a blueprint for “mass murder and enslavement.”[42]

Historian James Carroll wrote that, beginning in 1945, Forrestal “consistently exaggerated the dangers posed by the Soviet Union, and this exaggeration required two others—the regular overestimation of what Moscow’s military force could actually do, and the equivalent underestimation of American capabilities.”[43]

Among Forrestal’s political adversaries was Henry Wallace, FDR’s Vice President from 1941 to 1945 and an advocate of peaceful cooperation with the USSR, who said that Forrestal’s hands were “stained with oil.” This was owing to his work for the William A. Read & Company, which financed a number of oil companies with major holdings in the Arab world.[44]

Forrestal believed that, “if we are to safeguard western civilization, the British and American fleets must have free access to Near Eastern oil.”[45]

This access was threatened by the partition of Palestine and U.S. recognition of the State of Israel—which Forrestal argued would alienate the Arab countries who would be drawn into the Soviet orbit.

Forrestal warned, many would say presciently, that “unless the American support of the Zionist demands guaranteed that the rights of the Palestinians would be justly upheld and the boundaries of the new state explicitly drawn, the U.S. would alienate not alone the Arabs of the Middle East, but of the whole Moslem world … and the eventual harvest would be not a peaceful homeland for a race exhausted by persecution and massacre, but a reaping of a whirlwind of hate for all of us.”[46]

A vilification campaign in the media against Forrestal was spearheaded by arch-Zionist Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson, who wrote to his protégé Jack Anderson that Forrestal was “the most dangerous man in America” who, if not removed from office, would “cause another world war.”

Anderson later stated that Pearson had “hectored Forrestal with innuendos and false accusations.”[47]

According to researcher David Martin, among these was the allegation that Forrestal had gone insane under the pressures of Washington in the early Cold War. The story about Forrestal being found in the streets in his pajamas raving that the “Russians are coming” was made up.

John Birch Society Claims

Cornell Simpson, in a 1966 book on the assassination published by an imprint of the ultra-right John Birch Society, wrote that, while everyone knew

“political poisonings occurred in Italy in the days of the Borgias; that Caesar was stabbed to death in the Roman forum by Brutus with the complicity of other Roman Senators, but this has never been the American way—at least until recently … In the Forrestal case, the evidence not only indicates the possibility of murder, but it indicates that this crime may have been secretly masterminded by a Machiavellian group so powerful that it could cover up its crimes at the time and continue to suppress the facts even today.”[48]

Simpson is thought to be a pseudonym for a conservative writer, probably associated with the John Birch Society.

The Machiavellian group he referenced were the communists whom Simpson believed had infiltrated the Truman and Roosevelt administrations and wanted to eliminate “America’s first great activist fighter of communism,” and a man “most dangerous to international communism.”[49]

According to Simpson, Forrestal’s death bore an eerie resemblance to that of Czechoslovakia’s Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk—a friend of the West and strong anti-communist—whose 1948 murder two weeks after the Communists seized power was also staged to look like a suicide.[50]

There were also a number of State Department officials and politicians intent on exposing communist activities in the federal government who died under mysterious circumstances.

Among them was ex-U.S. Senator Robert M. La Follette, Jr., of Wisconsin—heir to a progressive dynasty and co-founder of the Progressive Party—who was found shot to death in his Washington apartment in February 1953 with a verdict of suicide—though there was no suicide note.

La Follette Jr. at the time was planning a potential political comeback and writing a book about how he had been “taken in” by communists on the staff of the House Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee Investigating Violations of Free Speech and the Rights of Labor”—an investigation into how various corporations evaded collective bargaining laws, underpaid workers and spied on and violently repressed organized labor.[51]

On the day of his death, La Follette’s wife had reported that he was in normal spirits and “gave no sign that he had any drastic act in mind,” while his office staff reported nothing unusual in his behavior.

His death thus had all the signs of a political murder.

The probable motive—different than the one suggested by Simpson—could be gleaned from The New York Times headline the day after. It proclaimed: “La Follette Death Ends Era in West; Hope for Progressive Comeback Diminishes—Party Once Was Supreme Power in State”

Forrestal’s Diaries

At the time of his death, Forrestal was intent on publishing his diaries which would have revealed explosive information.

The White House had ordered pages of Forrestal’s diary to be secretly removed.

David K. Niles, a top Truman aide, went over what was in the diaries for the period during Forrestal’s seven-week confinement; they had been removed from his Pentagon office and the contents vetted.

Initially, the diary amounted to more than 3,000 pages, though the posthumously published version was far shorter.[52] Revealing material about the FDR and Truman administrations was removed.

Monsignor Sheehy commented that, after comparing his many letters and notes from Forrestal with what allegedly were his friend’s own words in the published diaries, he was convinced that “much of the book is not as Forrestal wrote it, but instead was forged and ‘cooked up.’”[53]

Walter Millis, the New York Herald Tribune journalist and FDR apologist, tossed out more than 80 percent of Forrestal’s writing while editing the published version.[54]

Simpson believed that the missing material showed how the FDR administration had aided the communist cause and sold out to the communists.

The publication of Forrestal’s diaries in turn would have “jolted America into early awareness of the communist menace” and “inspired congressional investigations of treason in Washington” and helped oust the men who were destroying the American republic and helping the Soviet Union carve out a world empire.[55]

The latter assessment is characteristic of the paranoid worldview of the John Birch Society, though it is indeed plausible that the reputations of powerful men could have been destroyed by Forrestal’s revelations and that the McCarthyite witch-hunts would have commenced sooner.

Pearl Harbor Cover-up

Besides any ties to the Soviet Union during the 1930s and 1940s when it was an ally of the U.S., certain Washington power-brokers may have been concerned about revelations in Forrestal’s diary about the FDR administration’s conduct during the Pearl Harbor attacks—about which Forrestal had insider knowledge as the Under Secretary of the Navy at the time.

In his foreword to the edited diary, Walter Millis admitted he had arbitrarily deleted everything in the diary on the Pearl Harbor investigations, except for a single entry, itself mutilated by deletions.[56]

Millis did include one passage in which Forrestal discusses how he felt he had an obligation to Congress to continue the investigation into Pearl Harbor because he was not “completely satisfied with the report my own Court had made.”

This phrasing would suggest that Forrestal recognized that the government had been deceptive and wanted to uncover the truth.

Navy cryptographers at the time had cracked the Japanese code and intercepted Japanese military and diplomatic communications, resulting in advance knowledge of the Pearl Harbor attacks.

Either that foreknowledge did not make its way up to the highest chain of command or, more likely, the Roosevelt administration failed to properly warn naval commanders in Hawaii and allowed the attacks to go forward so the U.S. could launch a war against both Japan and Nazi Germany, which the public previously did not want.[57]

As under secretary of the Navy, Forrestal had helped suppress a Naval Inquiry report, headed by Admiral Orin G. Murfin, former commander of the Asiatic Fleet, which partially exonerated Admiral Husband Kimmel, commander of the Pacific Fleet, and Admiral Harold R. Stark, chief of Naval Operations, whom the Roosevelt administration had tried to blame for the “intelligence failure” at Pearl Harbor.

The Navy report emphasized that Kimmel and Stark had not “received all available information from Washington and could not be blamed for something [they] could not expect;” the lack of military preparedness was the fault of high-level government officials.[58]

It is possible that Forrestal was going to reveal the contents of the suppressed report in his diary and expose government deceptions about Pearl Harbor—which could not be allowed.

George C. Marshall—then the Army Chief of Staff—behaved particularly strangely on the morning of December 7, 1941.

At 10 a.m. (5 a.m. Hawaii time), when Marshall received word of the impending Japanese attack, inexplicably, he did not send the information to naval commanders in Hawaii via scrambler phone, which would have gotten the information there immediately and enabled them to launch a counter-attack.

Instead, Marshall sent it through regular courier and did not mark the message as urgent, ensuring that it arrived well after the Pearl Harbor attacks.[59]

Cornell Simpson pointed out that the version of Forrestal’s diary edited by Walter Millis rang false because of the “generally favorable tone” that is found there toward the man whom Simpson characterizes as Forrestal’s “perpetual antagonist—General George Catlett Marshall.”[60]

Marshall at one point is even characterized as the “nation’s outstanding soldier” and lauded for having “done a splendid job,” which Forrestal never would have written.[61]

The people who were behind the rewriting of Forrestal’s diary were very likely the same people who were behind his death.

The motive was clear in their desire to airbrush history and protect state secrets that might have cast doubt on the direction of U.S. government policy during the Cold War.

-

David Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal (Hyattsville, Maryland: McCabe Publishing, 2019). ↑

-

Townsend Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley, Driven Patriot: The Life and Times of James Forrestal (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 462. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 2. ↑

-

Hoopes and Brinkley, Driven Patriot, 465. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 11. ↑

-

Arnold A. Rogow, James Forrestal: A Study of Personality, Politics, and Policy (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1963), 23, 24; Cornell Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal (Boston: Western Islands, 1966), 16, 19. Johnson’s appointment was a payback for his raising over one and a half million dollars for Truman’s 1948 presidential campaign. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal; Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal. Forrestal had never been considered a suicide threat by the hospital; he was assigned to a room without a security screen and with long cords hanging from blinds that could be used as a noose. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal; Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 23. Both the Bethesda Naval Hospital and Pentagon refused to give out the men’s addresses after their transfers to researchers seeking information about Forrestal’s death. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 42. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 23, 24, 25. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 13. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 21. If the cord had snapped under Forrestal’s weight, one end would have been found still fastened to the radiator; however, the cord did not break and there was not a shred or mark on the radiator to indicate it had ever been so fastened. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 279, 280. Numerous victims of the U.S. deep state died from falls out of buildings, including Dr. Frank Olson, Edward Grant Stockdale, Kennedy’s ambassador to Ireland who was said to have known a lot about LBJ-crony Bobby Baker’s shady business dealings and about LBJ’s connection to the JFK assassination, and W. Marvin Smith and Laurence Duggan, State Department witnesses in the Alger Hiss case. ↑

-

“The Wilcutts Report: On the Death of James Forrestal,” http://ariwatch.com/VS/JamesForrestal/WillcuttsReport.htm. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 8. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 13; Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 16; Phillip F. Nelson, LBJ: From Mastermind to “The Colossus”: The Lies, Treachery and Treasons Continue (New York: Skyhorse, 2014), 227. ↑

-

Before he died, Forrestal had begun preliminary negotiations for buying one of the country’s oldest and most respected dailies, the New York Sun, which he wanted to transform into an aggressive anti-communist newspaper. Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 92. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 52, 53; Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 15. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 4. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 16, 17. ↑

-

“Historians Support Inquiry into the Death of James Forrestal,” History News Network, May 29, 2009; “The Wilcutts Report: On the Death of James Forrestal,” http://ariwatch.com/VS/JamesForrestal/WillcuttsReport.htm One of the persons approving the report was Dr. Winifred Overholser, the head of psychiatry at St. Elizabeth’s hospital in Washington D.C. who was involved in the CIA’s MK-ULTRA program and partook in mind control experiments.

-

“The Wilcutts Report: On the Death of James Forrestal,” http://ariwatch.com/VS/JamesForrestal/WillcuttsReport.htm ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 233; J.C. Hawkins, Betrayal at Bethesda: The Intertwined Fates of James Forrestal, Joseph McCarthy, and John F. Kennedy (North Charleston, South Carolina: Create Space Independent Publishing, 2017), 13. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 106. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal. The lack of proper investigation after the killing was evident in that other patients on the 16th floor with Forrestal were never interviewed to determine if they heard or saw anything suspicious. Hawkins, Betrayal at Bethesda, 11. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 278. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 18. ↑

-

“The Wilcutts Report: On the Death of James Forrestal,” http://ariwatch.com/VS/JamesForrestal/WillcuttsReport.htm; Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 185. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 17. ↑

-

William A. Read had made controversial loans also to Bolivia in the 1920s which were used to purchase arms from the Remington Arms Company for war against Paraguay. Rogow, James Forrestal, 26, 27. ↑

-

Hoopes and Brinkley, Driven Patriot, 107. ↑

-

Glenn Yeadon, The Nazi Hydra in America: Suppressed History of a Century (Los Angeles: Progressive Press, 2008), 368. ↑

-

Rogow, James Forrestal, 52, 120. ↑

-

Forrestal was an advocate for the racial integration of the U.S. Armed Forces. ↑

-

Hoopes and Brinkley, Driven Patriot, 184. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal, 325, 326; Hawkins, Betrayal at Bethesda, 20, 21. ↑

-

Hal M. Friedman, “Modified Mahanism: Pearl Harbor, the Pacific War, and Changes to U.S. National Security Strategy for the Pacific Basin, 1945-1947,” The Hawaiian Journal of History, 31 (1997), 192, https://www.readkong.com/page/modified-mahanism-pearl-harbor-the-pacific-war-and-3649774. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 67, 68, 69. Forrestal also had called for the redeployment of military advisers to Chiang’s army. ↑

-

Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal; Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 86, 147; The Forrestal Diaries, Walter Millis, ed., with the collaboration of E.S. Duffield (New York: The Viking Press, 1951), 57. ↑

-

Hoopes and Brinkley, Driven Patriot, 274. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 73, 74. Two of his envoys, Monsignor Sheehy and Judge Edmund L. Palmieri, worked to carry out Forrestal’s strategy that he mapped out to defeat the communists. Forrestal himself arranged for a shipload of American tanks, en route to Turkey, to be temporarily off-loaded in Naples and driven through the streets as further evidence of U.S. support for Alcide de Gaspieri of the Christian Democrats, to whom a lot of the money that he raised was delivered. Hoopes and Brinkley, Driven Patriot, 316. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 50, 51. ↑

-

James Carroll, House of War: The Pentagon and the Disastrous Rise of American Power (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006), 152. ↑

-

Jeremy Kuzmarov and John Marciano, The Russians Are Coming, Again: The First Cold War as Tragedy, the Second as Farce (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018); Rogow, James Forrestal, 28. Forrestal called Wallace a “hopeless dreamer.” Wallace said that Forrestal’s hands were stained also with “blood.” He was responsible, Wallace asserted in a dubious statement, for all the Jews killed in the ongoing fighting “against the oppression of Arab oil kings supported by Mr. Forrestal and men like him.” Glen H. Taylor, who ran as vice-presidential candidate on Henry Wallace’s third-party ticket, wrote to Truman that Forrestal’s removal from office was necessary “if our national policy is to be free from the taint of oil imperialism.” Townsend and Hoopes, Driven Patriot, 399. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 162. ↑

- David Martin believes that Forrestal’s anti-Zionism is what got him killed. Martin, The Assassination of James Forrestal; Hoopes and Brinkley, Driven Patriot, 403.

-

One unfounded accusation was that Forrestal had cowardly run out the back door when jewel thieves robbed his home. Rogow, James Forrestal, 28. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 44. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 49, 50. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 102. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 134, 135. La Follette had served as the private secretary of his father, Robert La Follette, Sr., a legendary figure in the progressive movement known as “fighting Bob,” and was a founder of the anti-war America First Committee in 1940. In 1946, he lost his Senate seat to Joseph McCarthy, though supporters were urging that he attempt to make a political comeback. At the time of his death, La Follette Jr. was Vice President of the Sears Foundation, which administered funds for philanthropic projects, chairman of the board of a radio station in Milwaukee, and a consultant to the United Fruit Company and had no financial worries. His wife had driven him to his office that morning and he left for home around 11 a.m. La Follette’s son Bronson told author Larry Tye years later that his father feared being interrogated by McCarthy about communist influence on his staff. ↑

-

The Forrestal Diaries, Millis, ed. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 87. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 82. Millis later worked for the Ford Foundation. Monsignor Sheehy commented that after comparing his many letters and notes from Forrestal with what allegedly were his friend’s own words in the published diaries, he was convinced that “much of the book is not as Forrestal wrote it, but instead was forged and “cooked up.” (Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 87). ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 92. ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal, 83. ↑

-

See Robert Stinnett, Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor (New York: Touchstone Books, 2001); Steve Sniegoski, “The Case for Pearl Harbor Revisionism,” The Occidental Quarterly, 6, 1 (Winter 2001). ↑

-

John Toland, Infamy: Pearl Harbor and Its Aftermath (New York: Berkley Books, 1983); 111, 113; Anthony Summers and Robyn Swan, A Matter of Honor: Pearl Harbor: Betrayal, Blame, and a Family’s Quest for Justice (New York: Harper & Row, 2016), 323. ↑

-

Stinnett, Day of Deceit; Sniegoski, “The Case for Pearl Harbor Revisionism”; George Morganstern, Pearl Harbor: The Story of the Secret War (New York: The Devin Adair Company, 1947). ↑

-

Simpson, The Death of James Forrestal. ↑

-

The Forrestal Diaries, Millis ed., 113, 179. ↑

No comments:

Post a Comment