Exclusive: Spike in Rare Brain Infections in Kids Raises More Questions Than Answers

The number of rare, life-threatening brain abscesses in children more than tripled in Southern Nevada in 2022, and hospitals in other parts of the country also reported unusual spikes. Two doctors interviewed by The Defender explained how the timing suggests COVID-19 vaccines could be a factor.

Miss a day, miss a lot. Subscribe to The Defender's Top News of the Day. It's free.

The number of rare, life-threatening brain abscesses in children more than tripled in Southern Nevada in 2022, triggering an investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which last week issued a report confirming the increase and calling for additional research to identify risk factors.

Doctors in other parts of the country similarly observed a spike in the number of cases in children since 2021, according to an NBC News report.

“In my 20 years’ experience, I’ve never seen anything like it,” Dr. Taryn Bragg told CNN. Bragg, an associate professor at the University of Utah, the only pediatric neurosurgeon in Nevada and the first to notice the spike, reported it to the CDC.

“After March of 2022, there was just a huge increase,” in brain abscesses, Bragg said. “I was seeing large numbers of cases and that’s unusual. And the similarities in terms of the presentation of cases was striking,” Bragg said.

Some media reports pointed to lowered immunity due to lockdowns during the pandemic as a possible explanation for the increase in cases. And two physicians who spoke with The Defendersuggested COVID-19 vaccines could be a factor — but to date, there is no official explanation for the spike.

Colds, sinus infections preceded brain abscesses in most cases

The CDC reported that in 2022, there were 18 cases of intracranial abscesses reported in Clark County, Nevada, up from an average of four cases per year from 2015-2021.

Most of the children in Nevada presented with colds or sinus infections that quickly progressed to abscesses forming in the brain, according to the CDC report.

A majority of the kids also showed the presence of the bacteria Streptococcus intermedius, which is commonly found in the oral and respiratory cavity, Bragg told Fox news.

“It often doesn’t result in infections, but it certainly can — and it’s the most common organism that will result in brain abscesses,” she said.

None of the children died, but many of them required long-term antibiotics and multiple surgeries.

Brain abscesses are rare events caused when a bacteria or fungi crosses the blood-brain barrier and enters the brain, usually because of infection or injury. The body forms an abscess — a pus-filled pocket — to stop the condition from spreading.

If untreated, an abscess can lead to brain damage or death.

In children, causes can range from bacteria that move to the brain because of untreated middle ear infections, endocarditis or immune deficiencies like HIV, or they can be caused by parasites, Dr. Peter McCullough, internal medicine doctor and cardiologist in Dallas, Texas, told The Defender.

‘It’s not just us. It’s hospitals all over the country.’

In May 2022, the CDC was alerted that three children in California were hospitalized concurrently for brain abscesses, also caused by Streptococcus intermedius.

In response, a team at the CDC led by Emma K. Accorsi, Ph.D., investigated a possible increase in pediatric streptococcal brain abscesses, epidural empyemas and subdural empyemas in California and other parts of the country.

Epidural empyemas and subdural empyemas also are pus-filled pockets that develop to protect the brain from an infection.

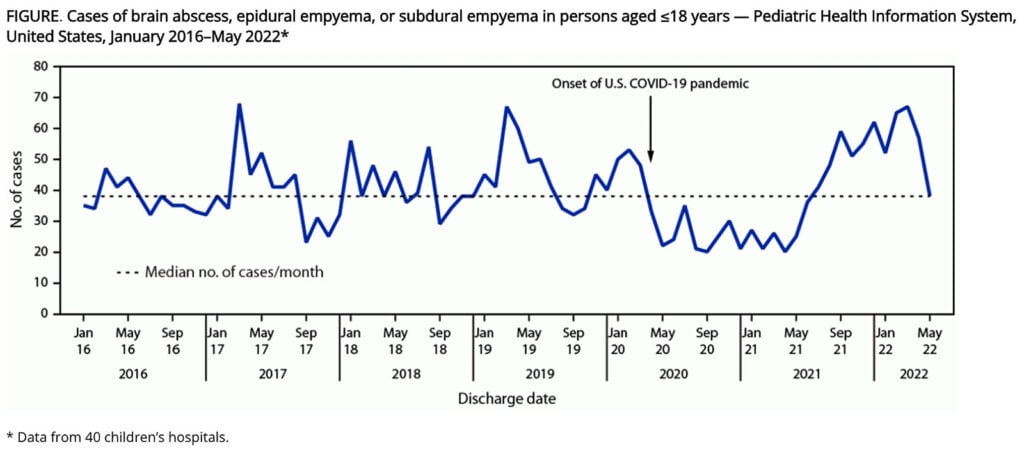

The CDC’s report on those cases, issued in September 2022, analyzed reports of brain abscesses in children from 2016 to 2022, and identified a national increase in pediatric brain abscesses in summer 2021, followed by a peak in March 2022, and then a return to baseline.

The CDC concluded the increase was “consistent with historical seasonal fluctuations observed since 2016.”

Another CDC report from August 2022 also reported a roughly 100% increase in brain abscesses, on average, across eight pediatric hospitals during the first two years of the pandemic.

Dr. Shaun Rodgers, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New York told NBC News his hospital is still seeing an above-average number of brain abscesses, a trend that started around the end of 2022.

“It’s not just us. It’s hospitals all over the country,” Rodgers said. “When we’re talking to colleagues, it seems like everyone is feeling that we’ve definitely had an uptick in these types of infections.”

What’s driving the spike?

Dr. Jessica Penney, an epidemic intelligence officer with the CDC and lead author on the CDC’s short investigation into the Nevada spike, told CNN she thought it was possible the spike was related to “immunity debt” from the lockdowns.

“Maybe in that period where kids didn’t have these exposures, you’re not building the immunity that you would typically get previously, you know with these viral infections,” Penney said. “And so maybe on the other end when we had these exposures without that immunity from the years prior, we saw a higher number of infections.”

Dr. Samir Shah, vice chair of Clinical Affairs And Education at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and a co-author of the report by Accorsi et al., made a similar argument to NBC News.

“As soon as we started to undo some of these [pandemic restrictions], you started to see the viruses come back, you saw more sinus infections, and then, not surprisingly, you ended up seeing more brain abscesses,” Shah said.

But schools largely re-opened in early 2021. “The kids had been out of lockdown for quite some time,” McCullough said. “So I doubt that’s a possibility.”

And in a later CNN report, health correspondent Elizabeth Cohen said the experts she spoke to also said pandemic restrictions likely weren’t the cause. Some even called the proposition “ridiculous.”

McCullough told The Defender it is important to note that the causes of abscesses are always multifactorial.

Clinically, he said, to diagnose the cause of a child’s abscess, a doctor would need to know, for example, if a child had taken a recent vaccine, if they had other immunoglobulin deficiencies, COVID-19, recent middle ear infections or congenital heart disease.

Commenting on whether the COVID-19 vaccine could be a contributing factor in the spike, McCullough noted two points from the Accorsi study, which analyzed cases from 40 hospitals across the country over several years and did a more detailed analysis of 94 cases identified through a national call for cases.

First, the rate of child brain abscesses does fluctuate seasonally and the abscesses in the study were in the range of normal fluctuation. But, the most recent 2021-2022 spike, since the vaccines became available, shows a more sustained rise than the previous spikes.

Also, only 25% of children with abscesses in the study had been vaccinated for COVID-19, but the study began in 2016, long before COVID-19 vaccines were available.

Given that, McCullough said, “Just by looking at that graph, I’d say the vast majority of kids who got the abscesses [in the 2021-2022 spike] were vaccinated.”

McCullough said a possible contributing cause could be “immune imprinting” where the vaccine basically distracts the immune system. The immune system constantly looks for the spike protein, thus impairing its capacity to function properly.

“It’s such a simple question to ask,” he said, adding that he doubts they ever will.

The FDA authorized the Pfizer vaccine for 16- to 17-year-olds on Dec. 11, 2020, 12- to 15-year-olds on May 10, 2021, and 5- to 11-year-olds in October 2021.

Dr. James Thorp, a board-certified obstetrician and gynecologist, also told The Defender the causes are likely multifactorial, and that he believes suppressed immunity related to COVID-19 vaccinations could play a contributing role in the spike in abscesses.

“There is ample evidence that COVID-19 vaccination causes immune injury and it increases the risk of infection not only to COVID-19 variants, but also to all other opportunistic infections, such as these,” he said.

Thorp said he also thought masking could play a contributing role because studies have found an increased risk of infections with masks.

Brain abscesses are rare events and there has been little research on their possible link to COVID-19 vaccines. At least one case of spinal cord abscess was linked to a COVID-19 booster in an adult, according to a study published in Vaccines.

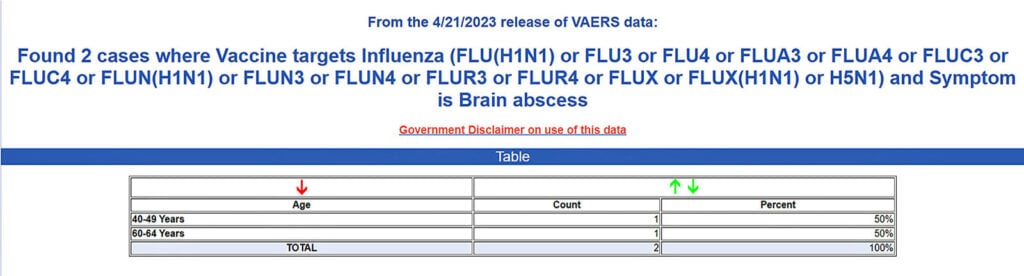

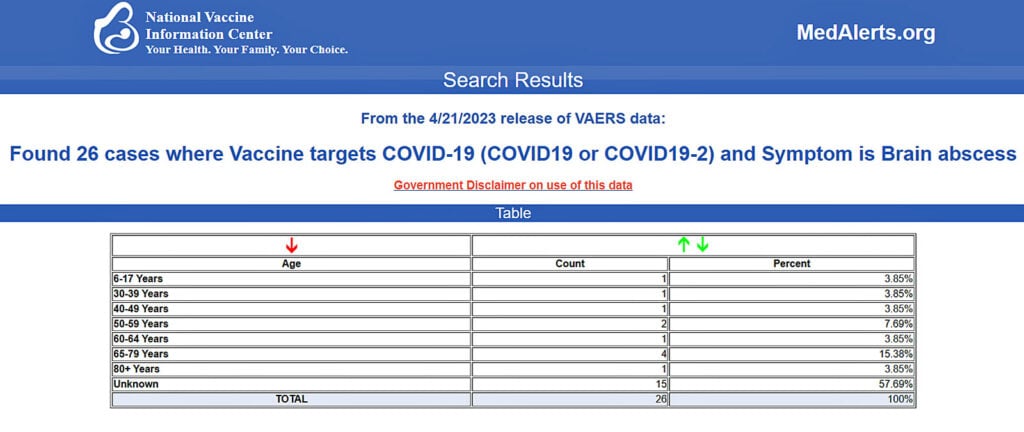

Brain abscesses following COVID-19 vaccines also have been reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). VAERS reports of adverse events don’t prove causality, but the CDC considers VAERS to be a key “early warning system” for detecting unusual or unexpected patterns of adverse event reporting that can signal safety problems with a vaccine.

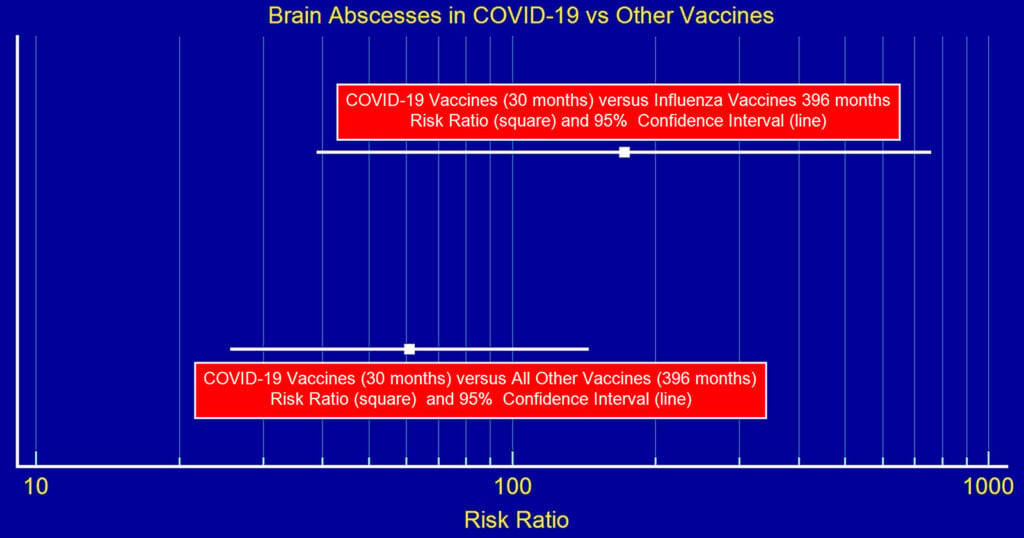

One common way to analyze VAERS data is through proportional reporting ratio (PRR) data mining, as recommended by the CDC/FDA. Using PRR, a researcher compares the reports of specific adverse events suffered after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine to reports made after receiving any other vaccine to see if there is an indication that the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines cause more adverse events than vaccines generally considered by the CDC to be safe.

Thorp said CDC/FDA’s “preferred” method of analysis favors the conclusion that a novel vaccine is deemed safe and effective because it compares new vaccines to existing vaccines rather than to a placebo. Those existing vaccines, regardless of how safe they are deemed to be, have a baseline of deaths and injuries associated with them.

That creates the false appearance of “safety” in the novel vaccine or at least diminishes that danger signal.

Thorp used the VAERS MedAlerts to perform this analysis on the VAERS data for brain abscesses reported as adverse events from vaccination among all ages.

He found that since 1990, when the VAERS database was created, there have been only two cases of abscesses reported for the influenza vaccine, versus 26 cases reported for the COVID-19 vaccine in just under 2.5 years, which, he said, is statistically significant (p<0.001).

He also compared the numbers of brain abscesses reported for COVID-19 to those reported for all of the vaccines in the entire VAERS database since 1990. He found there were only 13 abscesses reported for all other vaccines combined for that entire time period.

He also compared the numbers of brain abscesses reported for COVID-19 to those reported for all of the vaccines in the entire VAERS database since 1990. He found there were only 13 abscesses reported for all other vaccines combined for that entire time period.

Thorp graphed the data (below) to show the risk ratio — the likelihood of an event happening in one group versus the other. It is shown in the figure below.

“This is a significant danger signal,” Thorp said, “and merits urgent further investigation.”

10

10