The Great Stink of 1858

If

like me, you suffered through the blazing London summer of 2018 with

seemingly wall to wall sunshine heat and humidity from Easter to the end

of September, squashed on your commute in airless tube trains and

wondering how you’d ever get to sleep in a bedroom that rarely fell

under 30 degrees (90 F) at night then spare a thought for our Victorian

forebears. They had to endure

something very similar but with an added

toxic bonus of the Great Stink.

That year, the London Standard reported

temperatures of over 30C by the middle of June and the weather stayed

hot for several weeks. Like today there was no air-conditioning but

they also had no modern refrigeration which meant food was fresh for a

matter of hours at best and the old Roman sewerage system was not just

1800 years old but built for a population several million less than what

it had to cope with.

Everything you threw away back then ended

up in the River Thames. From the contents of people’s chamber pots and

the new-fangled flush lavatories, to dead dogs, decomposing food and

industrial waste, including animal parts from abattoirs and chemicals from leather tanning factories along the river.

The Thames embankment had not yet been

built, accidental drownings and river suicides were common and bodies

were rarely recovered from the water. It is said that the stench from

the Thames could be smelt from 7 or 8 miles away.

On top of this because everything was horse-drawn, the streets were full of massive piles of manure. Flies were swarming down on this and of course transmitting disease such as diarrhoea and typhoid.

It was a nauseating mix at the best of

times and the heat in 1858 made it worse. Standing close to the river

was enough to make you retch. It was dubbed the Great Stink but it was

no joke.

By the 1850s, London was the largest city

on the planet, with a rapidly growing population that had already topped

2.5 million – but it was struggling to provide its citizens with clean

water and sanitation.

In Little Dorrit, written that decade,

Charles Dickens described the Thames: “Through the heart of the town a

deadly sewer ebbed and flowed, in the place of a fine fresh river.”

Worse, Londoners drew their drinking water from the Thames and its tributary rivers,

which were often just as polluted. A condition called summer diarrhoea

was common, as was typhoid, while cholera killed thousands in a series

of epidemics. Conditions for those who lived in London was absolutely

horrific.

As the river runs throughout London. It’s

quite difficult to avoid and if you went anywhere near the riverbanks,

you would really be hit with this terrible smell that was referred to as

a miasma.

Report this ad

There

are many accounts of Londoners saying that they were being sick if they

went anywhere near because of the smell and they were trying to cover

their faces with masks or cloths.

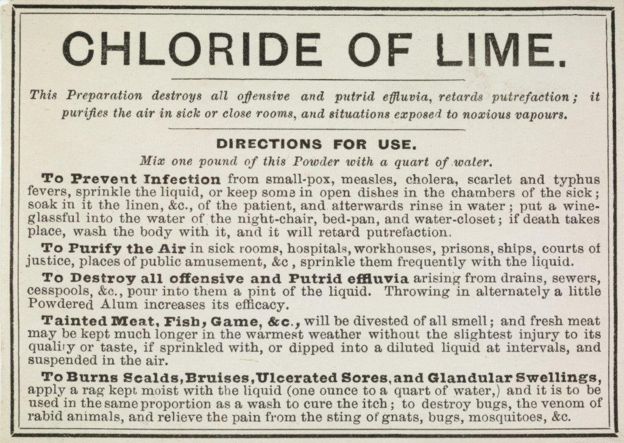

A Victorian effort to protect against Miasma.

In the newly built House of Commons, MPs

found it impossible to use rooms overlooking the river. The curtains

were doused with a product called chloride of lime.

Its manufacturers made extravagant claims

for its disease-preventing properties – but really it was little more

than air freshener, which had little impact on the appalling pong.

In a city that was once the worst affected by the Black Death and with

science still relatively simple, the smell, or miasma, was thought to

carry disease. If you could smell the stink then your life was on the

line, or so it was thought. That some diseases were waterborne was only beginning to be accepted.

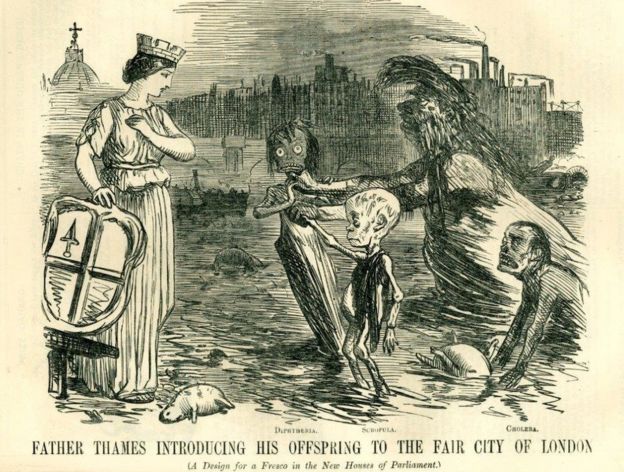

A ghastly cartoon from the satirical Punch magazine

Satirical magazines depicted Old Father

Thames as a filthy old man and his offspring as deformed and diseased.

At the height of the British Empire, the river which was assumed by

those around the world to be responsible for the vast amount of trade

and wealth coming into London was just as effectively becoming a river

of death for Londoners.

The

Great Stink wasn’t entirely a new phenomena, it had been a crisis that

had been building for a few years but this was a tipping point

especially as Parliament was not able to function during the summer

months.

Chancellor of the Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli, to proposed a bill, which MPs debated and passed within 18 days. On the 15th of July, Disraeli told MPs:

“That noble river, so long the pride and

joy of Englishmen, which has hitherto been associated with the noblest

feats of our commerce and the most beautiful passages of our poetry, has

really become a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable

horrors. The public health is at stake; almost all living things that

existed in the waters of the Thames have disappeared or been destroyed; a

very natural fear has arisen that living beings upon its banks may

share the same fate; there is a pervading apprehension of pestilence in

this great city.”

It became law on 2 August 1858, giving the

Metropolitan Board of Works the authority and cash to embark on the

biggest civil engineering project of the century the following year,

with Joseph Bazalgette in charge.

Bazalgette’s design was for a system of

interconnecting sewers, to capture London’s waste before it could reach

the Thames, and new embankments with sewers inside them. And so the

river was narrowed meaning that today the buildings can be at times out

of sight of the river and giving us the broad avenues and parklands

along the Thames.

The sewage was piped out to elaborately designed pumping stations, including Crossness and Abbey Mills.

It still went into the river but in less

populated areas so it was very much an- “out of sight out of mind”

project. It was a start to solve the problem and Sir Joseph Bazalgette

is something of a hero for his huge improvement in the public health of

London. No longer was there 45cm/18inches of sewage on top of the vast

river. His pumping stations continued for nearly 100 years when it

became unacceptable to pump raw sewage into the environment.

The Crossness Pumping Stattion

His sewage pipes are still working

perfectly though the system is currently being upgraded due to Londons

ever increasing population. Victorians were renowned for doing things

properly, to the best that science and engineering allowed and with

little regards for money. You can see that from the photos of how they

remain today.

Photo by Christine Matthews

No comments:

Post a Comment