During

the Covid pandemic, the U.S. government spent billions of dollars on

nearly 400 products intended to protect, diagnose and treat hundreds of

millions of people – all with the label “EUA” or “Emergency Use

Authorization.”

But what does EUA actually mean?

Even

before we answer that question, and by way of understanding where EUA

stands in relation to other pathways for authorizing or approving

medical products, it is helpful to look at what EUA is not:

If

we only understand one thing about EUA it should be this: EUA does not

apply to a product undergoing a clinical trial governed by FDA

regulations or other legal requirements.

EUA

is also not the same as Expanded Access Use (EAU), often called

“compassionate use” access, which applies to granting patients with

severe, incurable diseases access to experimental products before they

are fully approved.

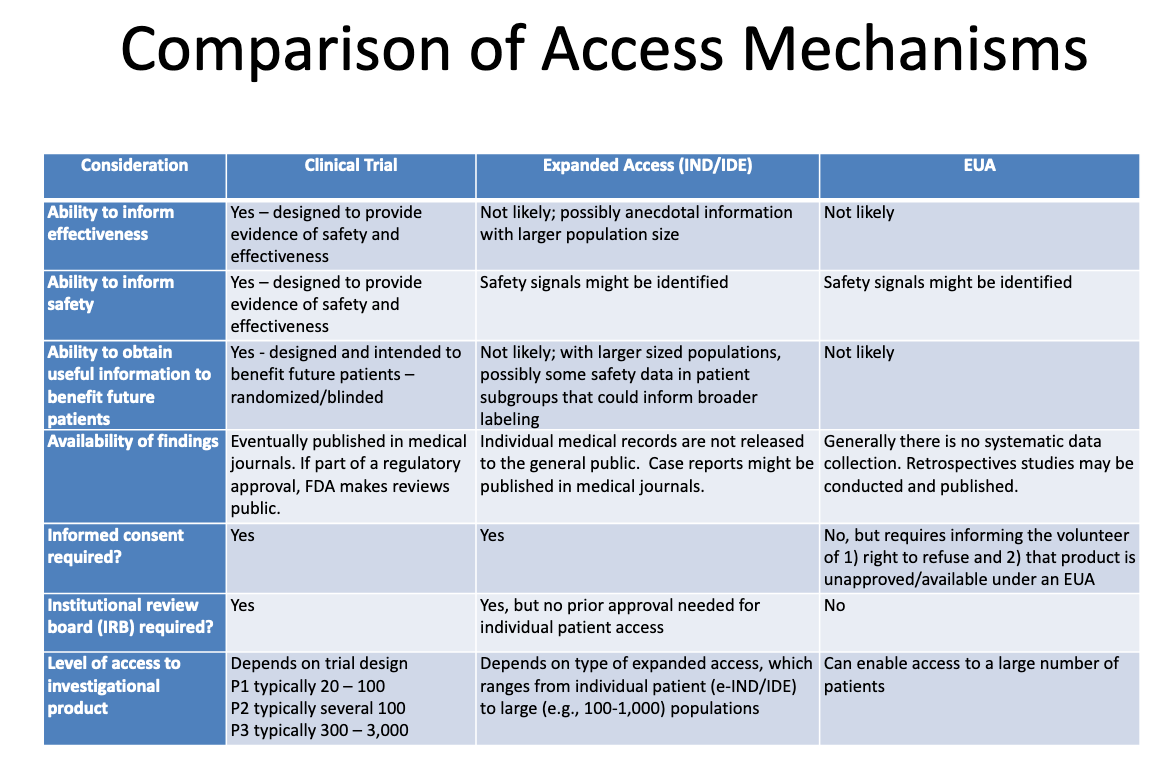

This table from an FDA-CDC 2020 presentation

summarizes the differences between products undergoing clinical trials,

products given to patients through expanded “compassionate” access, and

products authorized through EUA:

Here’s what this table tells us about EUA:

The process of granting EUA is not likely to generate any information about a product’s effectiveness.

The

process of granting EUA is not designed to provide evidence of safety

or effectiveness, but safety signals might be identified.

It

is unlikely, once a product is granted EUA and administered to some

patients, that any useful information will be obtained to benefit any

future patients.

There

is no systematic data collection on effectiveness or safety with EUA,

and no data is published in medical journals as part of the regulatory

approval process.

No

informed consent is required, but patients who “volunteer” to take the

product must be told they can refuse and that the product is

unapproved/available under EUA.

No institutional review board (IRB) is required. [IRB is a board that is supposed to protect the well being of human subjects in clinical trials]

To clarify even further how separate EUA is from any normal approval process, in a 2009 Institute of Medicine of the National Academies publication, we find this statement:

It

is important to recognize that an EUA is not part of the development

pathway; it is an entirely separate entity that is used only during

emergency situations and is not part of the drug approval process. (p.

28)

To summarize:

The

process of granting a product EUA is unlikely to generate any evidence

of safety or effectiveness. Once a product is granted EUA and

administered to patients, it is unlikely that any useful information

will be obtained to benefit future patients, because there is no

systematic data collection on effectiveness or safety.

Based

on all this very clear information from the CDC/FDA and the IMNA, it

would be fair to conclude that Emergency Use Authorization is a process

that should be applied very judiciously and only in cases of dire

emergencies.

Now let’s look at what types of emergency situations EUA is legally designed to address.

The

laws permitting the EUA “Access Mechanism” described above were drawn

up for cases of extreme, immediate emergencies involving weapons of mass

destruction (WMD), also referred to as CBRN (chemical, biological,

radiological, nuclear) agents.

Here’s how the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) describes its EUA powers:

Section 564 of the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 360bbb–3) allows FDA to strengthen public health protections against biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological agents.

With

this EUA authority, FDA can help ensure that medical countermeasures

may be used in emergencies to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or

life-threatening diseases or conditions caused by biological, chemical,

nuclear, or radiological agents when there are no adequate, approved,

and available alternatives (among other criteria).

These EUA powers were granted in 2004 under very specific circumstances related to preparedness for attacks by CBRN agents.

As explained in Harvard Law’s Bill of Health,

Ultimately,

it was the War on Terror that would give rise to emergency use

authorization. After the events of September 11, 2001 and subsequent

anthrax mail attacks, Congress enacted the Project Bioshield Act of 2004.

The record

indicates that Congress was focused on the threat of bioterror

specifically, not on preparing for a naturally-occurring pandemic.

Given

such a narrow type of truly extreme emergency situation involving a WMD

attack, it is understandable why the EUA “access mechanism” does not

require a lot of regulatory oversight or adherence to any manufacturing

or clinical trial standards.

So what the EUA access mechanism actually require?

Three things have to happen in order for EUA to be granted to a medical product:

The

Secretary of Homeland Security, the Secretary of Defense, or the

Secretary of Health and Human Services needs to determine that there is

an emergency involving an attack or a threat of an attack with a CBRN

agent or a disease caused by such an agent.

The FDA needs to make sure that it meets four “statutory criteria” when it issues the EUA.

The FDA has to “impose certain required conditions” in the EUA.

EUA Step 1: Declaring a CBRN emergency

The

emergency declaration for EUA is separate and unrelated to any other

emergency declarations that may be issued by the President, the HHS

Secretary, or anyone else. It must be issued specifically for the

purpose of activating EUA and can be ended or extended independently of

any other emergency declaration.

Here’s what the EUA law states are the four possible scenarios for activating the EUA “access mechanism”:

a

determination by the Secretary of Homeland Security that there is a

domestic emergency, or a significant potential for a domestic emergency,

involving a heightened risk of attack with a biological, chemical,

radiological, or nuclear agent or agents;

a

determination by the Secretary of Defense that there is a military

emergency, or a significant potential for a military emergency,

involving a heightened risk to United States military forces, including personnel operating under the authority of Title 10 or Title 50, of attack with—

a biological, chemical, radiological, or nuclear agent or agents; or

an agent or agents that may cause, or are otherwise associated with, an imminently life-threatening and specific risk to United States military forces;

a determination by the Secretary

[of Health and Human Services] that there is a public health emergency,

or a significant potential for a public health emergency, that affects,

or has a significant potential to affect, national security or the

health and security of United States

citizens living abroad, and that involves a biological, chemical,

radiological, or nuclear agent or agents, or a disease or condition that

may be attributable to such agent or agents; or

the identification of a material threat pursuant to section 319F–2 of the Public Health Service Act [42 U.S.C. 247d–6b] sufficient to affect national security or the health and security of United States citizens living abroad.

EUA Step 2. Meeting the statutory criteria

Once

one of the secretaries has declared that there is an emergency that

warrants EUA, there are four more “statutory criteria” that have to be

met in order for the FDA to issue the EUA. Here’s how the FDA explains these requirements:

Serious or Life-Threatening Disease or Condition

For

FDA to issue an EUA, the CBRN agent(s) referred to in the HHS

Secretary’s EUA declaration must be capable of causing a serious or

life-threatening disease or condition.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Medical

products that may be considered for an EUA are those that "may be

effective" to prevent, diagnose, or treat serious or life-threatening

diseases or conditions that can be caused by a CBRN agent(s) identified

in the HHS Secretary’s declaration of emergency or threat of emergency

under section 564(b).

The

"may be effective" standard for EUAs provides for a lower level of

evidence than the "effectiveness" standard that FDA uses for product

approvals. FDA intends to assess the potential

effectiveness of a possible EUA product on a case-by-case basis using a

risk-benefit analysis, as explained below.

[BOLDFACE ADDED]

Risk-Benefit Analysis

A

product may be considered for an EUA if the Commissioner determines

that the known and potential benefits of the product, when used to

diagnose, prevent, or treat the identified disease or condition,

outweigh the known and potential risks of the product.

In determining whether the known and potential benefits of the product outweigh the known and potential risks, FDA intends to look at the totality of the scientific evidence to make an overall risk-benefit determination. Such evidence, which could arise from a variety of sources, may include

(but is not limited to): results of domestic and foreign clinical

trials, in vivo efficacy data from animal models, and in vitro data, available for FDA consideration. FDA will also assess the quality and quantity of the available evidence, given the current state of scientific knowledge.

[BOLDFACE ADDED]

No Alternatives

For

FDA to issue an EUA, there must be no adequate, approved, and available

alternative to the candidate product for diagnosing, preventing, or

treating the disease or condition. A potential alternative product may

be considered “unavailable” if there are insufficient supplies of the

approved alternative to fully meet the emergency need.

EUA Step 3. Imposing the required conditions

Once

we have the EUA-specific emergency declaration, and once the FDA

determines that the product may be effective and that whatever evidence

is available shows that its benefits outweigh its risks, there is one

more layer of related regulation.

Here’s how a 2018 Congressional Research Service report on EUA explains this:

FFDCA

§564 directs FDA to impose certain required conditions in an EUA and

allows for additional discretionary conditions where appropriate. The

required conditions vary depending upon whether the EUA is for an

unapproved product or for an unapproved use of an approved product. For

an unapproved product, the conditions of use must:

(1) ensure that health care professionals administering the product receive required information;

(2) ensure that individuals to whom the product is administered receive required information;

(3) provide for the monitoring and reporting of adverse events associated with the product; and

(4) provide for recordkeeping and reporting by the manufacturer.

CONCLUSION

As

noted in this article, the FDA/CDC clearly recognize that the process

of granting Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) is unlikely to generate

any information about the effectiveness or safety of a product. When we

look at the letter of the law governing EUA, we see that this is,

indeed, a correct assessment.

The

EUA law does not impose any legal or regulatory standards that might

determine whether a product is safe or effective. The only standards are

whether the FDA believes the product may be effective and that its

known benefits outweigh its known harms. If there are no known harms or

known benefits, because the product has never been through the drug

approval process, the FDA can use whatever information or standards it

chooses to make that determination.

It

follows from all of this that a company whose product is a candidate

for EUA may attempt to demonstrate the product’s safety and/or

effectiveness through whatever means it chooses. The existence of such

an attempt (whether a clinical trial or other data-collecting

mechanism), and how that attempt is conducted, are all up to the

company. Nothing in the EUA law applies to how the company designs,

conducts or analyzes any studies or other data-collecting mechanisms it

chooses to pursue.

Applied to Covid products this means:

No safety or efficacy data from clinical trials were required in order for Covid products to receive EUA.

Any clinical trials referred to in the EUA process were conducted with no legally applicable regulatory standards.

More on the approval process for Covid vaccines here.

No comments:

Post a Comment