While much has been unflatteringly written about the extended silence of the beleaguered World Health Organization (WHO) in the current pandemic, and the current existential predicament it faces due to funding and support cuts, its notable contributions to global health cannot be ignored.

Since its inception, the WHO has to its large credit the successes of the battle against smallpox, reduction of TB and measles through mass vaccination programmes, and the near eradication of polio.

The WHO faces a crisis of credibility today. And while much can be blamed on its complex bureaucratic sloth, the one man at the centre of it—Dr. Tedros Adhanom, the director-general of the WHO—allegedly personifies the erosion in impartiality and rectitude expected from such a storied body.

As the world seethes at the WHO’s perceived partisanship and deliberate silence, it is important to segment the leader and the organisation for once- however Daedalian that might sound. As one delves into Tedros’s journey to the WHO, you are struck by how the mild-mannered Ethiopian leader might have some proverbial skeletons in the closet. A career politician with a carefully curated past who never let morality come in the way of political expediency, or a well-meaning man with unfortunate happenings under his command?

In understanding Tedros’s rise to head a global organisation, it is important to understand his origins and political choices early in life.

Origin story

Ethiopia is a beautiful country. One of the most rugged topographies in Africa, its rolling verdant hills, picturesque plateaus, massive lakes and the Blue Nile give it a certain geographical diversity and mystical élan, from the wet luxuriant savanna to the desert steppe.

One of the only African countries to pride itself at not being colonised by European powers (barring a brief five-year occupation by Italy before World War 2), Ethiopia was also one of the first independent nations to sign the Charter of the United Nations. At the forefront of Pan-African cooperation, it gave moral and material support to the decolonisation of Africa. No surprise then that the African Union headquarters sits in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital city.

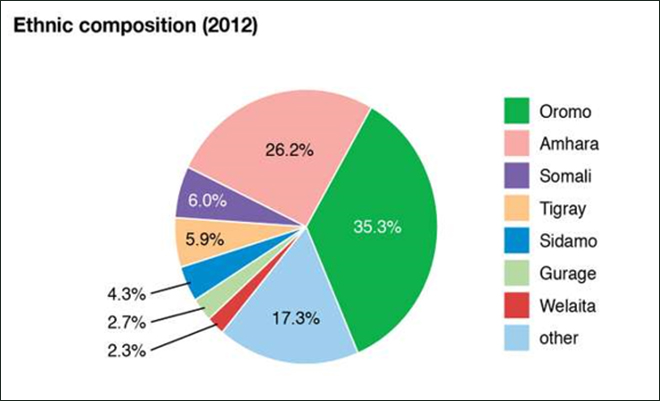

As with most of Africa, the country is very ethnically diverse, with differences primarily on linguistic categorisation. A mosaic of 100 languages that can mainly be classified into four groups, the key ethnicities of the country are Oromo, Amhara, Somali and Tigray, constituting more than 75 percent of the population.

Tedros was born in 1965 in Asmara, which became Eritrea’s capital after independence from Ethiopia in 1991, and grew up in northern Ethiopia’s Tigray region.

An ethnic Tigray, he became a member of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), an ethno-nationalistic movement to secure place for the Tigrays in national polity. TPLF has largely been in the seat of power (through a joint front), since overthrowing a regime perceived as being sympathetic to the Amhara ethnicity in 1991. Primarily, the Tigrays, a 6 percent constituent of the population of Ethiopia, hold most political power.

The better-known public alarms went off in 2017 when Tedros, soon after he was appointed the WHO chief, appointed Robert Mugabe, the much-maligned former Zimbabwean president, as a goodwill ambassador to the WHO. Clearly a quid-pro-quo for an electoral favour earlier, even the strongest supporters of Tedros were taken aback at the brazenness of the decision. Several former and current WHO staff said privately they were appalled at Tedros’s “poor judgement” and “miscalculation”. These words are critical as they occur in recurring frequency in the grey legacy left behind by the man in his more than three-decade professional span.

Systematic discrimination

It is interesting to note that Tedros started his political career by aligning with the TPLF, a hard-left organisation that later became part of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition of left-wing parties that ruled Ethiopia until last year (TPLF was classified as a terrorist organisation in the Global terror database). According to one Ethiopian newspaper, Tedros was listed as the third most important member of the TPLF’s politburo standing committee.

As an important TPLF member, Tedros joined the Ethiopian health ministry and rose through the ranks to become the country’s health minister in 2005. During his tenure, which lasted until 2012, he was credited for work done on reducing rates of HIV, measles and malaria.

However, it was also during this time that strong allegations emerged of the TPLF engaging in “systematic discrimination and human rights abuses” by refusing emergency healthcare to the Amhara ethnic group because of their affiliation with the opposition party. In 2010, Human Rights Watch wrote a report on how to aid in the form of food and fertiliser was withheld from local Amhara villagers.

Interviews by an observer group in 2009 with several people across three regions of Ethiopia yielded widespread suppression of political dissent by conditioning access to essential government programs on food and health. The report issued by the Human Rights Watch was scathing of how Tedros’s government used donor-supported resources and aid as a tool to consolidate power.

Given the strong ethnic fissures between the Tigray and the Ahmara ethnicities, these allegations started gaining credence further as birth rates were recorded to be significantly lower in the Amhara region compared to other regions and two million Amhara people “disappeared” from the subsequent population census.

Also, by the time Tedros left office as health minister, the Amhara region was severely underperforming in health indicators as compared to the Tigray region. The health coverage (physician to population ratio) was 5X apart in the two regions and infant mortality was vastly different.

If the times weren’t so grim, it would be laughable to think that a career politician, with allegations of discrimination in health provisions to his own countrymen would go on to lead the WHO, where universality and equality in healthcare are enshrined as core principles.

Covering up an epidemic

Going through Tedros’s resume, a carefully curated document for his bid for the post of director general of the WHO, it is interesting to note that there is a suspiciously hasty mention of his time as Ethiopian health minister—the seven key years of his professional career as a health minister and the primary qualification for his bidding. Yet these seven years are condensed into three points qualifying a little more than a passing mention.

While there is well deserved credit for expanding health infrastructure (although geographically selective), and the work on reducing HIV and malaria mortality, there is a curious omission of the epidemic of cholera in his resume.

Digging a little deeper, it is evident that Tedros was on a campaign to rewrite his questionable past on this aspect. Three disastrous cholera outbreaks occurred in Ethiopia (2006, 2009, 2011) under this watch as health minister. The response under Tedros was to first rechristen the outbreak to something less damaging. So cholera was suddenly—and wrongly—classified as acute watery diarrhoea (AWD) in the outbreaks in Ethiopia.

AWD is a potentially fatal condition caused by water infected with the vibrio cholera bacterium. Everywhere else in the world it is simply called cholera. But not in Ethiopia, where international humanitarian organisations privately admitted that they were only allowed to call it AWD and are not permitted to publish the number of people affected.

Tedros was apparently concerned about the international impact if news of a significant cholera outbreak were to get out, even though the disease is not unusual in East Africa.

But cholera bacteria were found in samples tested by external experts. As soon as severe diarrhoea began appearing in neighbouring countries, the cause was identified as cholera.

Somalia, which borders Ethiopia, battled a severe outbreak and a vaccine was deployed. However, the vaccine could not be released for Ethiopia without the government confirming that it was cholera.

Not only was there a strong allegation of Tedros covering up three cholera epidemics in his country and thus endangering surrounding states, he supposedly did this just to avoid international embarrassment. The terminology affected whether outside health organisations would marshal resources to fight an outbreak of the deadly bacteria.

A group of American doctors wrote to Tedros in 2017 saying, “Your silence about what is clearly a massive cholera epidemic in Sudan daily becomes more reprehensible”. “The inevitable history that will be written of this cholera epidemic will surely cast you in an unforgiving light,” they wrote, adding that Tedros was “fully complicit in the terrible suffering and dying that continues to spread in East Africa”.

Sounds familiar?

The views expressed above belong to the author(s).

ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

No comments:

Post a Comment