Why Are Nearly 300 Life-Saving Drugs in Short Supply? Big Pharma Will Make Too Little Profit.

Production of low-profit generic drugs has dropped off in the U.S., and patients and their physicians face shortages of critical medications — including chemotherapy drugs and IV nutrition for premature babies, CBS News reported on “60 Minutes.”

Miss a day, miss a lot. Subscribe to The Defender's Top News of the Day. It's free.

Production of low-profit generic drugs has dropped off in the U.S., and patients and their physicians face shortages of critical medications — including chemotherapy drugs and IV nutrition for premature babies, CBS News reported on “60 Minutes.”

Who is to blame? And what’s the solution?

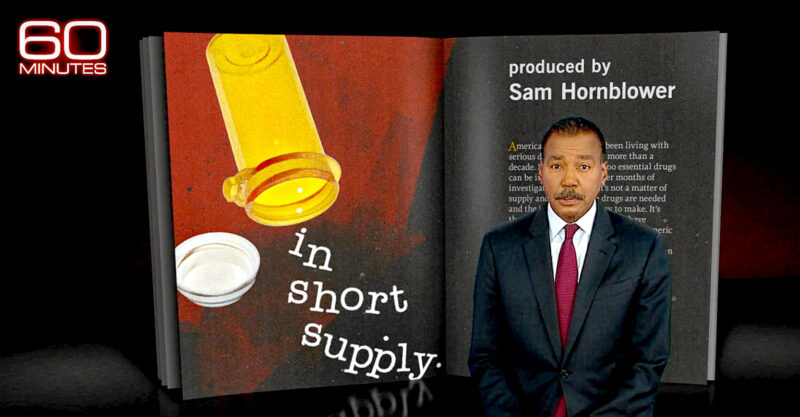

In a segment titled “In Short Supply,” “60 Minutes” host Bill Whitaker explored the issue of how U.S. hospitals have for more than a decade grappled with serious drug shortages.

It’s not a simple matter of a supply-and-demand imbalance, Whitaker told viewers. The problem is deeper and more complex than that.

“The drugs are needed and the ingredients are easy to make,” Whitaker said. “It’s that pharmaceutical companies have stopped producing many generic life-saving drugs because they make too little profit.”

“On any given day,” he added, “nearly 300 life-saving drugs may be in short supply in America’s hospitals.”

A May 24 search of The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) drug shortages database, “Current and Resolved Drug Shortages and Discontinuations Reported to FDA,” showed 126 drugs “currently in shortage.”

The number of drugs with ongoing and active shortages has been higher than 200 since 2018, according to the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, which maintains a site of drug shortage statistics.

Whitaker spoke with neonatologist Dr. Mitchell Goldstein of Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital in California, who said he is deeply concerned about shortages affecting premature babies in neonatal intensive care units.

Goldstein told Whitaker parenteral (IV) nutrition for premature infants is in short supply, although it’s made with simple ingredients such as minerals, salts and glucose, items “found in any college chemistry lab,” he said.

“I think about the babies I take care of … it’s horrible,” Goldstein said.

“It’s like being in a siege and you’re running out of ammunition. Sometimes we look at it and it’s just, ‘How are we going to survive this next day, the day after … and what is the new problem? What’s on the horizon? What’s going to happen next week?’”

Shortages ‘standard operating procedure’

Dealing with shortages has become “standard operating procedure in the world of parenteral nutrition over the past decade — and these shortages are putting hospitals’ smallest and most vulnerable patients at risk,” according to experts who spoke at the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition’s Malnutrition Awareness Week in October 2021.

The parenteral nutrition shortage has been an issue since at least 2010, according to a 2013 piece in Today’s Dietician, which explained that producing parenteral nutrition drugs isn’t particularly profitable, “as only a small, specialized population requires them.”

The group Physicians Against Drug Shortages also began sounding the alarm about drug shortages years ago, claiming on its website:

“Most of the approximately 361 drugs in short supply are sterile injectables administered in hospitals, outpatient facilities, and clinics.

“They include chemotherapy agents for ovarian, colon, bladder and breast cancer, leukemia and Hodgkin’s disease; anesthetics and pain relievers; antibiotics; IV nutrients for malnourished infants, and many other generics that have been saving lives for decades.”

The public became more aware of drug availability problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, but hospitals have been dealing with shortages long before COVID-19 came along, the head of the pharmacy at Loma Linda told “60 Minutes.”

In fact, hospitals commonly hold weekly drug shortage meetings, in which staff members discuss how to stretch, substitute and possibly ration prescriptions.

A shortage of the drug vincristine, an older, generic medication used in chemotherapy regimens, occurred in 2019 when manufacturer Teva stopped making it due to its low-profit margin.

Pfizer, then the only remaining maker of the drug, had to pause vincristine production for six weeks due to a quality control problem.

Vincristine was developed in the 1960s and costs about $5 per dose. “60 Minutes” spoke to two mothers of cancer patients who took to social media to plead with Pfizer to get the medication to their children:

A ‘broken system’

When a drug patent expires (typically 20 years after its development) and the drug becomes generic, it is much less profitable for manufacturers.

That’s why drug companies often simply stop making generics, even if demand is high.

Today, 40% of generic drugs have just one manufacturer, according to Whitaker.

“I don’t understand how companies in good conscience can make those kinds of decisions,” Ross Day, former director of group purchasing organization (GPO) Vizient, told “60 Minutes.”

“None of these companies are poor companies. They have the opportunity to not make as much [money] on one drug and still make plenty of margin and profit on other drugs.”

Another option is for the government to step in, said Day. “The government could play a role in keeping some of these drug manufacturers viable,” he said.

“This is just as much of an emergency in my mind as the pandemic is.”

Bill Simmons, a former generic drug executive, reminded Whitaker that profits keep drug companies in business. Decisions to cease making generic drugs are unfortunate but may be economically necessary to keep a plant operating, he said, pointing out, “corporations aren’t charities.”

Additionally, a medication’s path from manufacturer to patient is complex, and a web of middlemen reduces profit every step of the way.

This “broken system” is the root cause of drug shortages, said Whitaker.

Day and Simmons lay some of the blame on GPOs, which act as “gatekeepers” that negotiate drug prices for hospitals collectively in an effort to reduce costs.

GPOs negotiate more than $250 billion in hospital purchases annually, according to Whitaker. The biggest three GPOs are Healthtrust, Premier and Vizient.

Lower costs for hospitals — and high fees to GPOs — mean less profit for drug companies.

“We are systematically shutting down all of our U.S. manufacturing because we do not pay enough money for the drugs to the manufacturers,” Simmons said.

Watch the “60 Minutes” segment here:

Sign up for free news and updates from Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and the Children’s Health Defense. CHD is implementing many strategies, including legal, in an effort to defend the health of our children and obtain justice for those already injured. Your support is essential to CHD’s successful mission.