The “Good” Liberal

November 30, 2018

Let us look at the verbal meaning. The root is liber (“free”). TheSuch generosity, at least in intellectual matters, would seem a natural result of the freeing of the individual from the religious and cultural traditions of pre-Renaissance and pre-Reformation Europe.

term liberalis (and liberalitas) implies generosity in intellectual and material matters.

Up to the beginning of the Nineteenth century the word “liberal” figured neither in politics nor really in economics.

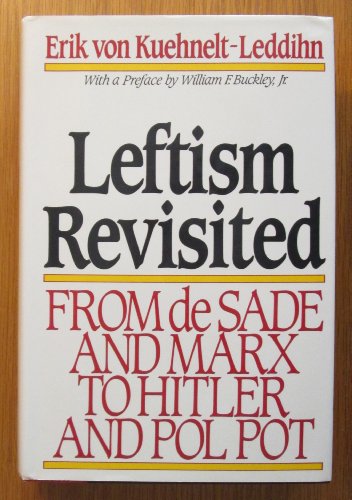

Leftism Revisited: Fro...

Best Price: $47.03

Buy New $124.00

(as of 09:45 EST - Details)

For his timeline, he points to the first use of the term in

politics or economics in 1812 Spain. The revolutions in both America

and France at the end of the eighteenth century would mark a more

appropriate starting point; I think the distinction in events is

important, even though the few decades separating EvKL’s timeline and

mine seem rather insignificant.

Leftism Revisited: Fro...

Best Price: $47.03

Buy New $124.00

(as of 09:45 EST - Details)

For his timeline, he points to the first use of the term in

politics or economics in 1812 Spain. The revolutions in both America

and France at the end of the eighteenth century would mark a more

appropriate starting point; I think the distinction in events is

important, even though the few decades separating EvKL’s timeline and

mine seem rather insignificant.He describes the Manchester School of the eighteenth century as “pre-liberal,” as forming or advancing ideas that we would be realized both politically and economically:

We are referring here to the Manchester School whose philosophical (or theological) roots were deep in the soil of deism. God, the Great Architect, had created the world nearly perfect. All evils were due to human intervention which upset the Divine plan.As God’s creation was nearly perfect, what was required was for man to intervene as little as possible in state or society:

If state and society never intervened in commerce and industry, these would automatically flourish, while all artificial limitations, rules or regulations-for instance, guilds, labor laws, tariffs, currency reforms, etc.-would bring about the downfall of prosperity.A libertarian can easily agree with the issue of non-interference by a state actor in commerce and industry. This causes one to wonder: if God’s plan is perfect and it is beneficial for man to not intervene in matters of commerce, why is not beneficial that this perfect plan not also be interfered with in the social, cultural and religious fields. In other words, why not remove the interference into God’s perfect plan by these voluntarily-formed societal institutions?

EvKL finds a mix of Calvinism and the Renaissance in this pre-liberal thought. There is much good in the offspring of this marriage; for example, one cannot deny the valuable economic progress. I have written elsewhere about the dangers – especially about the focus on the individual at the expense of all possible reasonably voluntary governance institutions.

Next comes the early liberal phase – the phase that EvKL first associates with the “good” liberal.” Such as these were active primarily in the first half of the nineteenth century:

Though perhaps not entirely unaffected by deism, it had to a large extent the leadership of thinkers with decided religious affiliations or at least strong sympathies for the Christian tenets.I cannot parse out the distinction between “not entirely unaffected by deism” and “strong sympathies for the Christian tenets.” Deists hold strong sympathies for the Christian tenets: they appreciate the ethic and they believe in the watchmaker.

The distinction hinges on troublesome features such as the Virgin Birth and physical Resurrection. Once these are taken as myth, the slippery slope has begun to the loss of Christian ethics. No eternal life? Well, then: he who dies with the most toys wins. I am not sure when the slippery slope hit bottom; maybe World War One?

Liberty or Equality: T...

Best Price: $11.99

Buy New $13.68

(as of 03:50 EST - Details)

Liberty or Equality: T...

Best Price: $11.99

Buy New $13.68

(as of 03:50 EST - Details)

We rightly cringe when greed is blamed for the economic woes of the last decades – as if greed is something new. Instead, perhaps, it is that the belief in the reality of eternal life was the now-missing regulator of greed.

So, I do not see a very clean distinction between the pre-liberal phase and the early liberal phase: the pre-liberals (as EvKL labels these) gave us the two most important liberal revolutions in history – this cannot be swept aside; both phases were driven by a religious view based on something less than the Christianity of the Bible.

He offers the names of several contributors to this early liberal phase. While I am not familiar with each of them, of the ones I am familiar it is safe to say that they are those that Classical Liberals and libertarians would point to and say “this is what we mean by ‘liberal.’”

These “good” liberals were influenced by some aspect of the monotheistic God as depicted in the Christian Bible:

Many of these early liberals were not lovers of freedom besides being Christians but took their political inspiration either directly from Scripture or from theology.To these “good” liberals, there was no freedom outside of Christian ethics and some selected aspects of the theology; yet, this should not be taken to mean anything more than Deism, given my reading here and elsewhere. The benefits of the ethics without the foundation for the ethics – a house built on sand.

Man has an immortal soul, man has a personality, man is not an accident of blind forces of nature, man needs freedom because God wants him not only to develop his personality in the right direction but also to live a moral life, freely (but rightly!) choosing between good and evil.Good and evil under whose definition? It is easy to proclaim a Christian ethic; it is difficult to sustain a Christian ethic without an institution in a position of authority behind it. No, for the one-thousandth time, I am not calling for theocracy. One need not find in every moral transgression a physical punishment here on earth.

When the Church excommunicated a king, it did not throw him in prison; it was the king that had the army, after all, not the Church. Yet, this excommunication often worked to modify the king’s behavior.

EvKL points to the broader denominational affiliations of such liberal thinkers:

From the aforementioned it is obvious that the religious aspect of early liberalism was more strongly developed among Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and those supporters of the Reformation faiths who had broken with the strict views of the Reformers, who were “Erasmian” and Zwinglian rather than Calvinistic or Lutheran.Liberalism finds its way into the various Reformation faiths only in the eighteenth century: one cannot say that Luther or Calvin were in any way “liberal.”

Menace of the Herd or ...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

Menace of the Herd or ...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

One cannot be but struck by the broad array of denominations of the individuals that in some way or another contributed to the development or advancement of liberal thought. They had one thing in common, an unfortunately unstated premise, perhaps; a premise without which all of their writing about liberty was in vain. The writing was based on the assumption that such liberal thought was meaningless if not built on the Christian foundation from which it came.

But why state it in a Europe and America in which all were Christian – albeit by now of multiple denominations? It would be, perhaps, like writing about a market economy with the unstated premise that it was humans who were to participate. Who would have to state such a premise? (And I know one of you will find an article about how chimpanzees are seen to be trading via indirect exchange…. What next? The vote?)

EvKL does offer that the political side of liberalism carried more sway in those from the Catholic faith while the economic side of liberalism was better appreciated in the Reformed. It is an interesting distinction, perhaps one that finds light today in the debates about moral versus pragmatic and economic arguments regarding liberty.

EvKL continues to describe in some detail the political evolution of the times, the ideas of equality and individual that transformed their aversion to democracy into an embrace of democracy: one man, one vote. Ultimately, this led to the forces of the left dominating, as has been seen throughout the west since at least the beginning of the twentieth century – coinciding with the birth of the period we today label as Progressive.

There were now, mostly in central Europe, thinkers who viewed the problem of liberty in a different light than the men who belonged to a somewhat older generation and in many ways could have been called their teachers. (Almost all of them, to be sure, as far as economics go, had been inspired by Ludwig von Mises.)He describes these as “neo-liberals,” interestingly, when it comes to economics; they met at the Mont-Pèlerin Hotel in 1946…

…these newer lights were less radical in their outlook and they admitted curbs on mammothism and colossalism to preserve competition. They thought that the state had a right and even a duty to correct possible abuses of economic freedom…I only mention this point for completeness; as it is not the focus of my post, I will leave it here – but will certainly welcome comments on this topic. It is the next point that most interests me:

Yet probably more important than this change was the reappraisal of religion, especially of Christianity. Many of the neoliberals declared that it is not sufficient to prove that “liberty delivers the goods,” that freedom is more agreeable or more productive than slavery. There must be philosophical and even theological reasons why liberty must be achieved, fostered, preserved.EvKL cites Professor Wilhelm Röpke, who says even if it is proved that a planned economy is materially superior, he would still prefer freedom. A somewhat different view than that held by libertarians who see material improvement as the measure of liberty.

Under these circumstances sacrifices of a material order would have to be made to preserve the dignity of man.Them’s fightin’ words in many libertarian circles. But one sees just this in the economic laws of the Middle Ages. While infinitely less onerous than what we face today, a handful of laws restricting the absolute freedom of the private property owner in relation to his property.

From such views we can deduct that the neoliberals had, in a certain way, a greater affinity with the early liberals than with their immediate predecessors.As EvKL writes, they “they refused…to make a fetish of economics.” Such as these “refused to deal with economics in an isolated way, detached from all the other disciplines.”

Conclusion

Indeed, we have before us two problems to be solved: first, to find out how it happened that liberalism in the United States evolved into the very opposite of what it set out to be-if it did “evolve”!-(thereby morally forfeiting the right to call itself “liberal”), and second, later on, to analyze what conservatism, old and new, really stands for or, at least, ought to stand for.Yes. An interesting question, that of the “bad” liberalism” and this transformation from good to bad. Presumably to be addressed by EvKL in his next chapter, entitled “False Liberalism.”

Reprinted with permission from Bionic Mosquito.

No comments:

Post a Comment