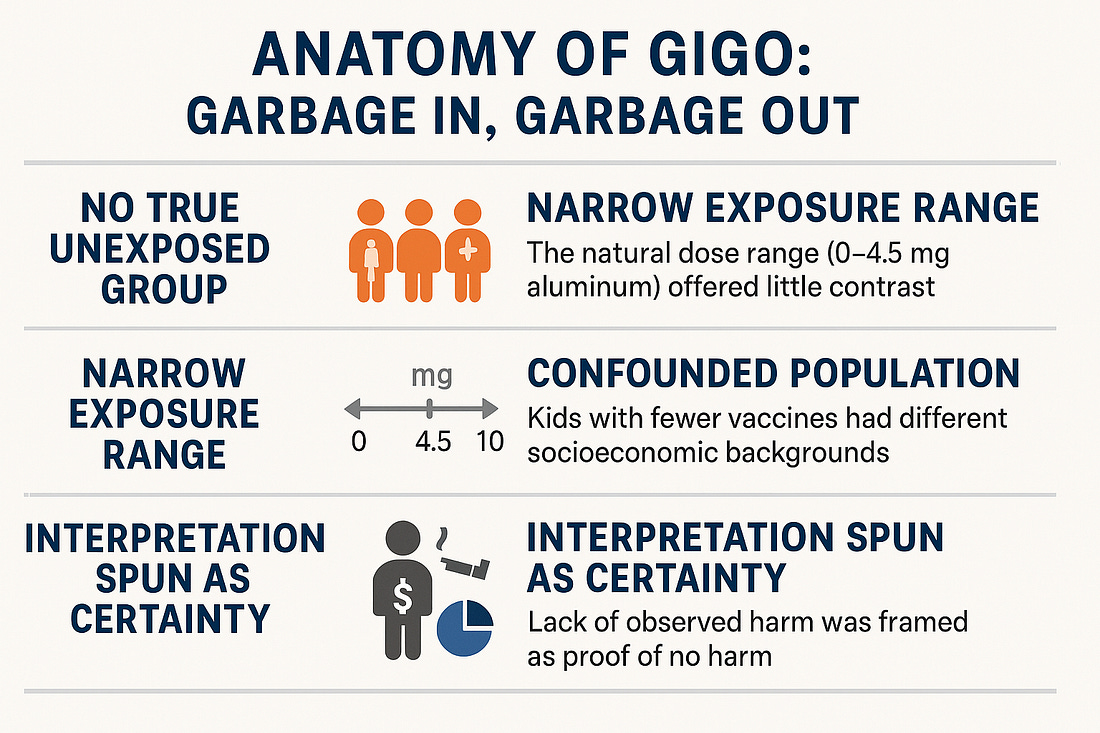

No Evidence of Harm? A “Garbage In, Garbage Out” Analysis of the Aluminum Vaccine StudyThe dataset is massive, but if the inputs are poorly contrasted and confounded, then your statistical power just lets you confidently detect nothing — which is exactly what happened.A new observational study led by Prof. Anders Hviid – and promoted heavily by Prof. Jeffrey S. Morris – claims to find “no evidence of harm” from aluminum-containing vaccines in children. The dataset includes over 1.2 million Danish children, a size that, on the surface, seems to scream reliability. 🙄☝️No matter how many statistical angles you run, if the inputs are structurally biased — narrow dose range, no true unexposed group, and strong confounding — you’re still running variations on a weak signal.

But dig a little deeper, and you’ll find a textbook case of how to spin noise into confidence. Let’s walk through it. This is a textbook case of GIGO (“Garbage In, Garbage Out”). Here’s why:

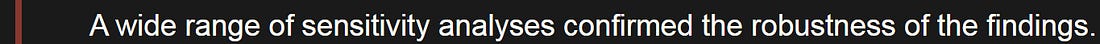

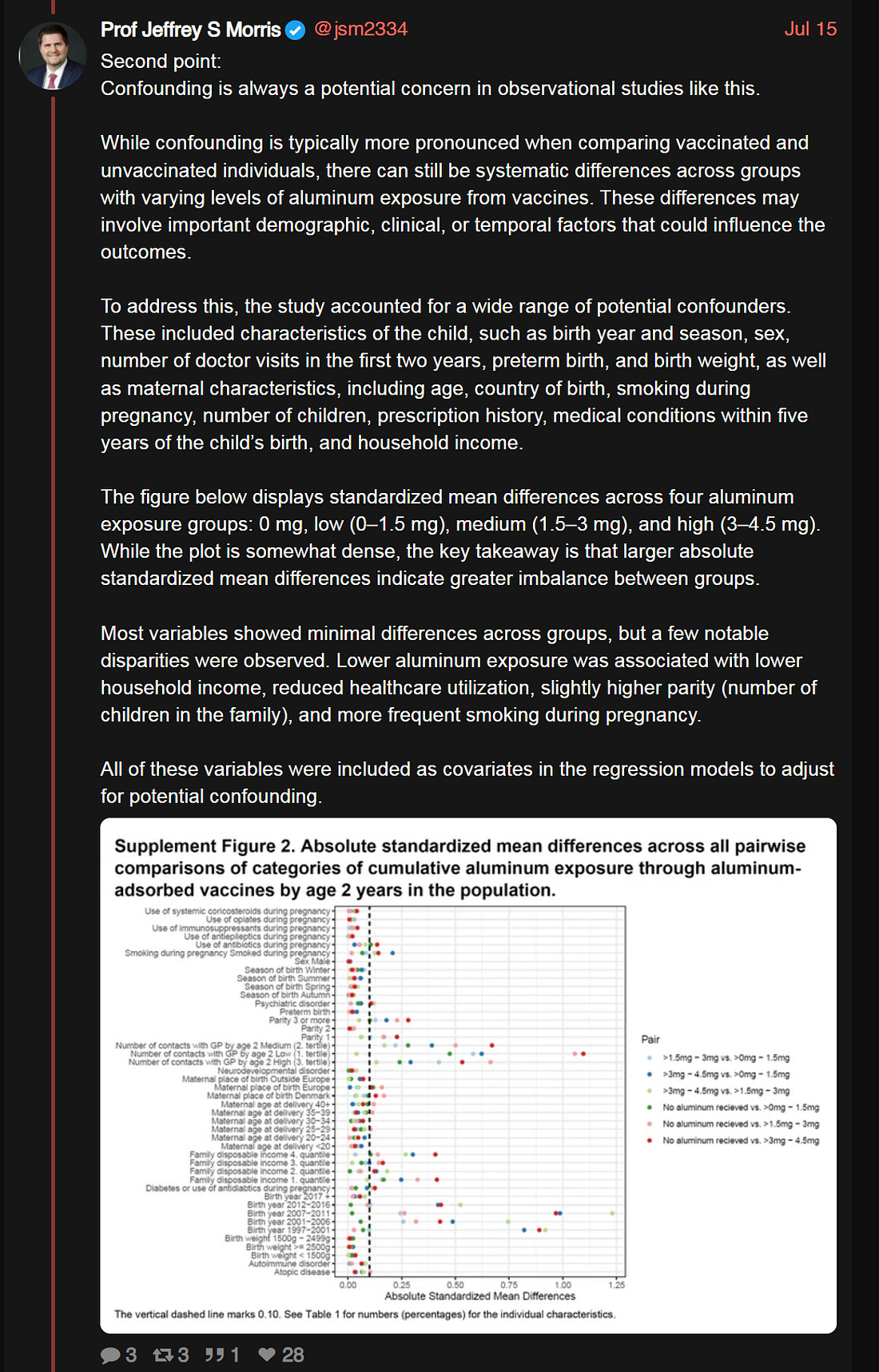

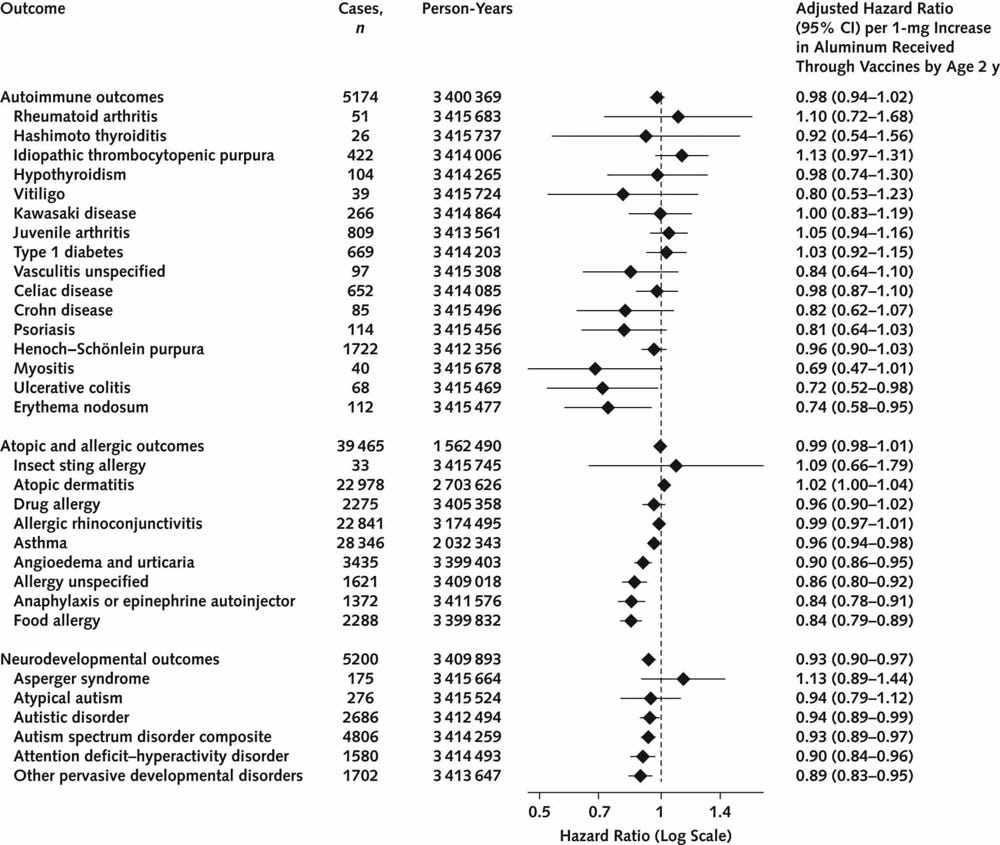

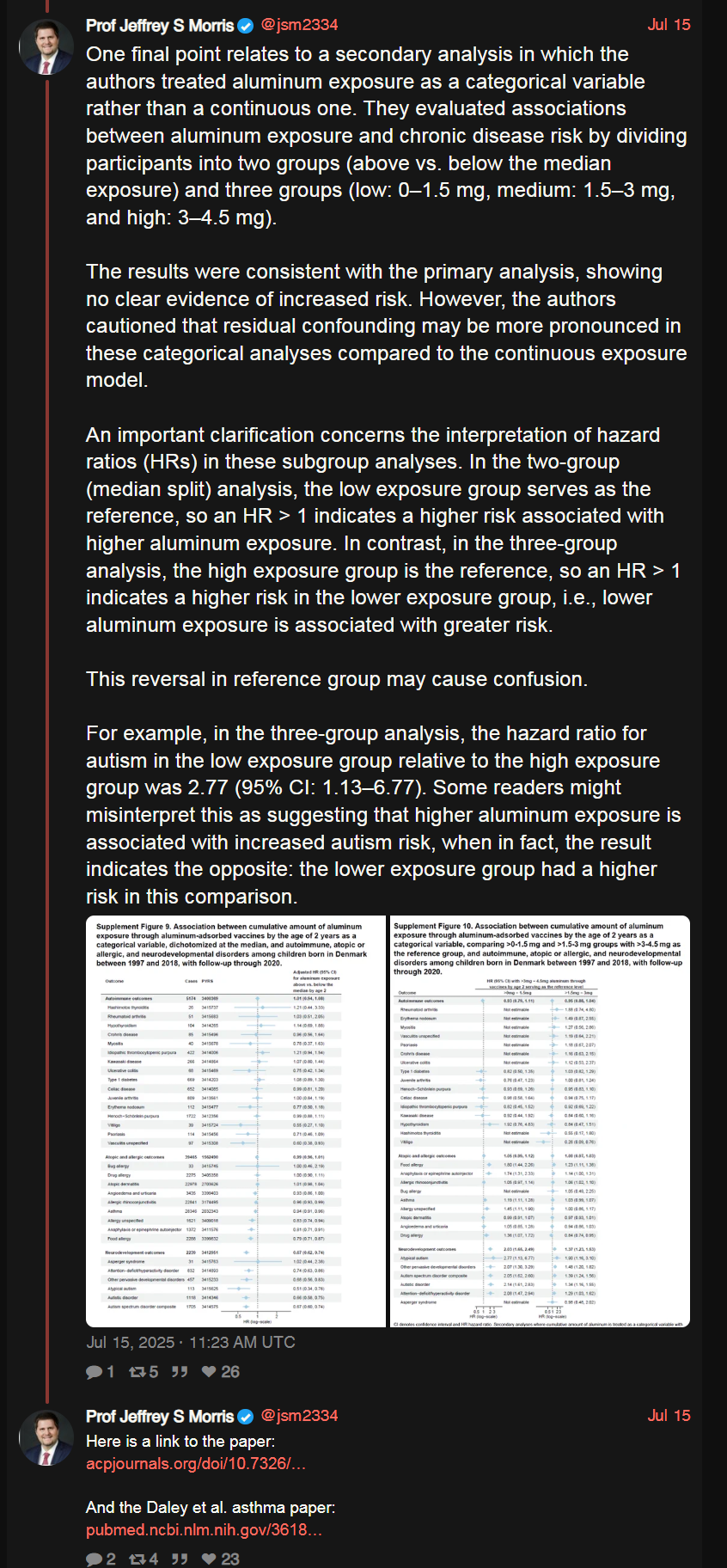

Now, let’s walk through each of these points in detail. No True Unexposed GroupThere were virtually no completely unvaccinated children in the cohort. Only about 15,237 children (1.2%) received zero aluminum-containing vaccines by age 2. In other words, the study compared “high” vs. “slightly less” aluminum exposure among an almost fully vaccinated population. With such high coverage, the absence of a true unexposed control group makes it nearly impossible to detect effects that might only appear when comparing to genuinely unexposed kids. The natural dose variation was also small. The median total aluminum from vaccines was around 3 mg by age 2 (maximum ~4.5 mg). A narrow dose range means little contrast in exposure, which translates to little statistical power to see any difference in outcomes. If everyone’s aluminum exposure is clustered in the same ballpark, subtle harm from aluminum (especially if it only manifests beyond a certain threshold or in a binary on/off way) would remain hidden. In short, the study was not set up to find what it wasn’t truly looking for. Assumed Dose-Response, but None ObservedThe authors operated on a dose-response assumption: If aluminum were harmful, higher doses should lead to greater risk. They indeed looked for a trend – calculating hazard ratios per 1 mg increase in aluminum – and found no such dose-response for any of the 50 conditions studied. They used that absence of a gradient to declare safety. In their view, if more aluminum doesn’t correlate with more illness, aluminum must not be causing illness. However, biology isn’t always that linear. A threshold effect – where even a low dose can trigger the maximum impact – would produce a flat dose-risk curve. Once you’re above the threshold that causes harm, additional dose might not increase the damage much further. In that scenario, you’d see no dose-response gradient even if harm exists (because everyone in the study is already past the harmful threshold). Thus, no observed dose effect does not automatically mean no harm. It might simply mean the study lacked participants with truly low (or zero) exposure to reveal a difference. The absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence in this case. Confounding Still Looms LargeYes, the researchers statistically adjusted for many covariates – socioeconomic status, birthweight, preterm birth, season of birth, maternal smoking during pregnancy, etc.. But let’s be honest: adjustments aren’t magic. Children who received fewer vaccines were not a random subset of the population; they came from different households (often poorer, with higher rates of maternal smoking and perhaps less engagement with preventive healthcare early on). These differences don’t vanish just because you feed them into a model. Every observational study is at the mercy of residual confounding – factors we either can’t measure or don’t even realize are skewing the groups. If this Danish study had shown a positive association (harm), every critic would be shouting that “correlation isn’t causation” and that confounding variables must be to blame. (In fact, that’s exactly what happened when a 2022 U.S. study reported a possible aluminum-asthma link – it was met with caution that it could be confounded.) It’s funny how that standard gets suspended when the result is comforting. When the outcome aligns with what public health officials want to hear (i.e., “no harm detected”), many are suddenly willing to treat an observational result as near gospel truth, confounding be damned. Healthy Vaccinee Bias — The Quiet SaboteurForest plot of adjusted hazard ratios (log scale) for selected outcomes per 1 mg increase in aluminum exposure by age 2. Most outcomes (black diamonds) cluster around 1.0 (no effect). Notably, some outcomes – including autism spectrum disorder and asthma – show hazard ratios slightly below 1.0 (to the left of the dotted line), implying lower observed rates of those diagnoses among children with higher aluminum exposure. Ironically, the study actually found that children who received less aluminum (fewer vaccines) had higher rates of certain conditions (autism, asthma, allergies) in some analyses. For example, the hazard ratio for autism spectrum disorder was around 0.93 per mg of aluminum – meaning autism was slightly less common in kids with more aluminum exposure. Asthma was also marginally less common with higher exposure. Does that mean aluminum prevents autism and asthma? Of course not. Even the authors and Morris have acknowledged this likely reflects selection bias (often dubbed “healthy vaccinee” bias). One plausible explanation is that some parents halted or delayed further vaccination after noticing early developmental red flags or health issues in their child. Those children, already on track to develop autism or asthma, thus ended up with lower aluminum exposure by age 2. In other words, the arrow of causation is reversed: the (incipient) condition caused reduced vaccination, not the other way around. So the data’s slight protective signal is almost certainly an artifact of who continued vaccinating versus who didn’t, rather than any true protective effect of aluminum. As Hviid himself noted, the lower autism rate among more vaccinated kids is “not interpreted as [a] relevant protective effect”. Fair enough. But here’s the rub: If this kind of bias can create a false appearance of protection, it could just as easily hide a real harmful effect. Bias is a two-edged sword. In this case it likely masked any small risks of aluminum by making the fully vaccinated group look unusually healthy. The study attempted some bias analyses (they even did an analysis excluding the unvaccinated entirely, and extended follow-up to age 8, still finding no difference), but one can never completely eliminate such effects in observational data. Selective Standards, AgainIn late 2022, a U.S. observational study of ~326,000 children (using Vaccine Safety Datalink data) found a modest increase in risk of asthma (~20–30% relative increase) associated with cumulative aluminum exposure in vaccines. At the time, experts urged caution: it was just one study, could be confounded, “correlation ≠ causation,” etc. The finding was noted as interesting but not definitive. Now fast forward to 2025: we have a null result in a larger dataset, and suddenly some of those same voices are calling it “robust and nearly definitive.” Prof. Morris, for instance, has characterized the Danish study as extremely rigorous and essentially conclusive in dismissing aluminum concerns. What changed? Only the outcome. The skepticism seems to vanish when the narrative aligns with what the medical establishment wants to hear. When a signal of potential harm appears: “slow down, more research needed.” When no signal is found: “see, it’s safe – case closed.” This selective standard is not how science is supposed to work. One should apply equal scrutiny to all results, especially when public health credibility is on the line. To be clear, larger sample size and careful design do lend more weight to the Danish study’s null findings than to any single positive study. But treating it as the final word – when it shares the same fundamental limitations of observational design – is premature. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; it’s simply inconclusive in a more precise way. Overstated CertaintyEven the authors admit they cannot rule out small risks. In the paper, they explicitly state that while moderate or large increases in risk were not seen, “small relative effects, particularly for some rarer disorders, could not be statistically excluded.” Morris, however, is touting this result like a mic-drop moment: issue settled. The study’s size and thoroughness appears likely to rule out any large or even moderate dangers from aluminum in childhood vaccines. But risks, delayed effects, or harms confined to susceptible subgroups are ignored. The data only tracked children up to age 5 (and in some analyses, age 8). It cannot speak to outcomes that manifest later in adolescence or adulthood. Nor can it fully address extremely rare conditions where even 1.2 million children isn’t enough to detect a difference. In other words, “no evidence of harm” is not the same as

“evidence of no harm.” Yet the public messaging glosses over that

nuance. The authors themselves, as noted, were careful to include

caveats. But the way this study is being presented to the world by

enthusiasts like Morris is with overstated certainty

– as if it’s a definitive all-clear on aluminum. That goes beyond the

data and ignores the study’s own acknowledged limitations. “No evidence of harm” vs “evidence of no harm”:

It may sound like semantics, but it’s a critical scientific

distinction. “No evidence of harm” simply means this particular study

didn’t find a statistically significant risk. But “evidence of no harm”

implies we’ve confidently proven safety — a much

higher bar. Imagine scanning a field with a metal detector and finding

nothing. You now have “no evidence of buried coins.” But if your

detector is weak or the coins are buried deep, that doesn’t mean there

are no coins — only that you didn’t detect them. The Danish study

provides absence of evidence, not evidence of absence. Yet the public soundbite often skips the nuance and emerges as: The Bigger PictureStepping back, there’s a larger issue of transparency and trust. This Danish dataset is essentially sealed; outsiders cannot inspect the raw data or the full analysis code. The research was conducted via Denmark’s national health registries, which are not open-access databases. Even someone like tech entrepreneur turned vaccine-safety activist Steve Kirsch – who has the resources and motivation – cannot obtain the underlying data. When Kirsch (politely) challenged the lead author for access or for a debate on methods, he was rebuffed and even blocked. In other words, the study’s conclusions rest on a black box of data that we just have to trust was analyzed correctly and without undisclosed bias. We’ve seen this pattern before. Freedom-of-information requests for vaccine safety data often come back with heavily redacted documents or years-long delays. Transparency is promised in theory, but in practice data gets shielded behind privacy laws or institutional policies whenever someone wants to verify findings independently. Now, we’re asked to believe that this time is different – that this sealed analysis should be taken at face value because reputable authorities say so. That’s like asking someone with a gun to your head not to worry because the court declared them innocent. Trust, but can’t verify. It’s a precarious position to be in, especially given the erosion of public confidence in recent years. Open science would call for anonymized data to be made available for re-analysis, or at least a third-party audit. Instead, we’re effectively told “take our word for it.” Legal Push?One practical response to this opacity could be a legal challenge to compel data transparency. Imagine a lawsuit forcing the release of the full dataset and the internal methodology behind this study for independent scrutiny. Well-funded skeptics could potentially go to court to demand access to the data that the publishers and authors have thus far kept closed. Even if unsuccessful, the pressure of litigation might encourage the researchers or the journal to allow an independent re-analysis, or else face questions about why they won’t. If the study is as bulletproof as advertised, it shouldn’t need to hide its data. Sunlight would only strengthen its conclusions. The mere fact that we have to consider lawsuits to see data speaks to how fragile the foundation of some of these “trust us” studies really is. In science, replicability is key. If results only hold under proprietary conditions and secret datasets, then confidence in those results – no matter how many millions of data points or prestigious institutions are involved – will understandably remain shaky for some. (See Prof. Morris’s public commentary in his own words here: his Twitter/X thread, where he applauds the study and discusses some of these points.) Even with full transparency, the critical flaws would remain:

Well…The study may be large and peer-reviewed, but size alone can’t compensate for design limitations. And peer review is no guarantee against entrenched bias. Meanwhile, Prof. Morris, someone who saw fit to unfollow and then block me on social media (reportedly because I was “smart and attractive,” but I digress), continues broadcasting confidence from behind that wall of dismissal. Pardon the sarcasm, but I don’t understand jealousy of the weak. My critiques aren’t born from envy; I challenge because I care. I learn because that’s the most beautiful part of being human, the ability to question and seek truth. If this study were really as rigorous as they claim, it wouldn’t need so much spin. And it wouldn’t need to fear scrutiny. The data would be open, the debates welcomed. Until that’s the case, forgive some of us for not simply taking it on faith that aluminum in vaccines got a clean bill of health. In science, answers don’t get to hide behind size alone, they must stand up to the light. Sources

Association Between Aluminum Exposure From Vaccines Before Age 24 Months and Persistent Asthma at Age 24 to 59 Months What would happen if the government required AI models to tell the truth? The

median cumulative aluminum exposure for the cohort was 3 mg, with a

range from 0 mg to 4.5 mg. Only 15,237 children received no

aluminum-containing vaccines during the study period

|

No comments:

Post a Comment