How To Keep Your Dentist From Killing Your Labrador Retriever (and other pets)

A government analyst reveals the pesticide scandal killing household pets around the world.

My

dog made me write this. Her name is Gia. She’s ten. That’s her in the

photo above. Gia loves normal Lab stuff like frisbee and swimming, but

as for me, I spend most of my time in a cubicle in Washington, D.C.

where I am an intelligence specialist at the Federal Bureau of

Investigation. Raisins

aren’t an investigative priority for FBI analysts

but if I explained how they came on my radar, you wouldn’t believe me

anyway. So let’s just get right to the story.

Luckily

for me, this isn’t a tale about Gia. But it is about a black and white

Shetland Sheepdog named McGee. McGee was your typical beloved household

canine. He was a rescue dog, a little overweight and a lot

over-excitable, especially when it came to that magical time of the

evening when his human housemates returned home from wherever it is

humans go all day. He was the perfect gentleman, always greeting guests

with a toy and waiting his turn as the humans doled out raisin treats to

his rabbit siblings.

Sure,

McGee confiscated the occasional unattended sandwich or helped himself

to a portion of fragrant trash now and then. But should such acts be

punishable by death?

He

had eaten raisins many times before and they proved to be nothing but

little bits of sweet, shriveled heaven. Neither McGee, his human

housemates, or the veterinarians who treated him during his final days

at the Metropolitan Emergency Animal Clinic in Rockville, Maryland had

any idea raisins could send McGee to heaven directly.

But

in January 2001, the humans left 18 ounces of raisins on the coffee

table. Was this an oversight on their part or a gift for their favorite

canine? The humans didn’t say, so being a glass-half-full kind of dog,

McGee interpreted the situation as the latter. Within hours, he started

vomiting repeatedly. By day two, he couldn’t walk. McGee died that week

of kidney failure. The veterinarian who treated him originally suspected

rat poison, but later determined the culprit was his raisin snack. It

was the first documented case of raisin toxicity in Maryland.

The

veterinarian community has not yet figured out why raisins are toxic to

dogs so I wrote this assessment to help point them in the right

direction. Here is a summary of the chain of events that I propose led

to McGee’s death:

- In 1949, short-sighted federal policy implemented in the aftermath of WWII causes the overproduction of raisins in California;

- By the 1980’s, raisin growers resort to using millions of pounds of a fluoride-based pesticide called cryolite to control insects on a massive monocrop of raisins in San Joaquin Valley;

- In 1989, Europeans prove fluoride accumulates on grapes treated with cryolite after they measure high levels of fluoride on the California wine they are importing;

- Also in 1989, the ASPCA begins noticing a trend of raisin toxicity in dogs but discounts pesticides after wrongly assuming the FDA is monitoring for them;

- In 1996, the EPA reregisters the use of cryolite on food crops by pointing to unsubstantiated dental claims of the safety of fluoridation;

- In 2001, McGee steals a box of California raisins from the coffee table.

The

detailed explanation of what killed McGee is long, so if all you want

to know is how to keep your dog safe from dentists, skip to the last

paragraph. It has all the information you need to protect your favorite

canines from raisin toxicity. (Plus, Gia insisted we finish by including

her cutest puppy pic ever, all in an effort to entice you to share this post and

help spread the word. The photo is of baby Gia trying to figure out how

stairs work, but she does it all wrong. It’s tough being a canine in a

world built for homo sapiens.)

Raisins shouldn’t be another lesson dogs need to learn the hard way.

I. Raisins and War

The

story of American raisins begins around 1870 when advancements in

irrigation and railroad transportation enabled large-scale commercial

raisin production in California. With water piped in from the Sierra

Nevada River, the central and southern San Joaquin Valley became a

particularly popular spot for raisin crops because of low rainfall in

autumn months while the grapes are drying.

In

1912, Fresno area raisin growers formed the California Associated

Raisin Company chaired by H.H. Welsh. They launched their first

marketing campaign two years later during the outbreak of World War I.

Raisin

prices skyrocketed during the war as the military purchased them as a

cheap snack for troops. The U.S. Food Administration provided credit to

European allies who imported California raisins by the boatload. Boiled

raisin cakes, known as “war cakes” made without milk or eggs, became a

symbol of American resourcefulness and were sent in care packages to

troops overseas. Raisin production increased during the war to meet

demand, but farmers were devastated after the war when prices plummeted.

By

World War II, federal regulators learned their lesson. Again, the

demand for raisins surged, this time in the face of the Nazi threat.

In

1942, the War Production Board ordered California’s entire wine grape

crop to be made into raisins. Raisin vineyard acreage expanded as prices

soared from $48 per ton in 1939 to $312 per ton in 1946. Things really

got serious when mock mincemeat pies filled with raisins replaced

traditional mincemeat pies filled with other stuff.

This

time when the war ended, the government was ready with a foolproof

plan, or so they thought. Raisin farmers would continue to grow obscene

amounts of raisins but to keep prices high, they would only be allowed

to sell a portion of their crops. The rest would be seized by the

government and squirreled away in raisin bunkers for a rainy day World

War. Or they would be sold to foreigners at low prices to devastate

raisin farmers overseas. At the very least, they would be fed to

disappointed schoolchildren and confused cows.

It was an ingenious idea. What could go wrong?

The

plan was implemented in 1949 as part of the New Deal when the U.S.

Department of Agriculture promulgated Marketing Order 989 which created

the National Raisin Reserve and the Raisin Administration Cartel that

would run it. Instead of selling raisins directly on the free market,

U.S. raisin growers shipped their raisins to a raisin “handler” who

separated the raisins owed to the federal government and paid the grower

only for the remainder.

Technically,

the Raisin Administration Committee was supposed to pay raisin growers a

share of profits made on the sale of reserve raisins. But even during

years when they generated $65 million in sales, there was nothing left

over to share with raisin farmers who, for the most part, were happy

they didn’t have to think up their own raisin commercials and were

content with the inflated prices they were receiving on the domestic

market.

Speaking

of raisin commercials, you might remember this part of the story. At

the height of the raisin cartel glory days, a government grant of $3

million was added to existing raisin funds to help boost sales abroad

with a marketing campaign about a raisin claymation musical group called

The California Raisins who

released four studio albums, starred in their own Saturday morning

cartoon show, were featured in an Emmy award-winning Christmas special,

and were permanently enshrined at the Smithsonian Museum of American

History.

Meanwhile

in the target market in Japan, concerned Japanese parents complained to

television stations in Tokyo about the shriveled potato grabbing his

crotch in front of their frightened children. Other Japanese viewers

mistook the raisins for chocolate candy.

The

campaign eventually ran into legal trouble when raisin farmers argued

the advertisements cost nearly twice what the California producers were

earning from extra raisins sold in Japan.

As

good as the idea of a National Raisin Reserve sounds, the cache never

came in as handy as government officials must have thought it would, and

yet it persisted until June 2015

when the U.S. Supreme Court sided with a stubborn farmer named Marvin

Horne who refused to let the government seize his raisins. After 66

years, the National Raisin Reserve was finally deemed unconstitutional

and it was abolished.

“This is an interesting story, Melissa, but what does it have to do with dogs?”

My

goodness, can’t a woman write about raisins for a few thousand words

anymore? I haven’t even made any raisin’ puns yet, or clever plays on

the words grapes and wrath.

As I was about to say,

now that you know the story behind California raisins, you can see how

well-intentioned government policy has been causing the over-production

of raisins in California for generations.

The

National Raisin Reserve, and the government-backed marketing that went

with it, explains the longtime mystery of why raisins are given out as

healthy treats at Halloween instead of personal-sized packets of

dehydrated apples, pineapple, or papaya, to give just a few examples

(hint, hint). It also explains why in America, raisins are seen as “the

cool, hip dried fruit for kids” while prunes, which are basically just

big raisins, are used solely to deconstipate old people.

Raisins

are the most popular dried fruit in the United States, accounting for

approximately two-thirds of total dried fruit consumption. That’s not

fair.

The

story of California raisins also shows how the U.S. grew to become the

largest exporter of raisins in the world, exporting to nearly fifty

countries and producing almost half of the world’s raisin supply — all

from within a 60-mile radius of Fresno.

II. Raisins and Fluoride

Over

time, monocrops become more difficult to protect as nature intervenes

in an attempt to restore biodiversity to the region. Natural threats

develop resistance to pesticides and new species of threats are

encountered when opportunistic predators move in. Eventually, some grape

growers began using a pesticide called cryolite which acts as a fatal

stomach poison in grapeleaf-greedy bellies.

Your

dentist might not be familiar with cryolite but it played a pivotal

role in the most enduring legacy of the early U.S. dental establishment:

fluoridation of the public water supply.

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofascial Research (NIDCR) tells the story best.

It started as an observation, that soon took the shape of an idea. It ended, five decades later, as a scientific revolution that shot dentistry into the forefront of preventive medicine. This is the story of how dental science discovered — and ultimately proved to the world — that fluoride, a mineral found in rocks and soil, prevents tooth decay.

As

the NIDCR’s story goes, in 1909 a young dental school graduate named

Frederick McKay left Pennsylvania to open a dental clinic in Colorado.

When he arrived in Colorado Springs, he was appalled to see many of the

townspeople’s teeth were splotched with permanent stains the color of

chocolate candy (their analogy, not mine). McKay joined forces with H.V.

Churchill, an industry chemist from the Aluminum Company of America

(Alcoa) who was researching a similar phenomenon in the company town of

Bauxite.

McKay

and Churchill discovered that fluoride was the cause of the unsightly

stains on people’s teeth. The community water shed in Colorado Springs

was high in fluoride because it contained deposits of cryolite from the

rock formations of Pike’s Peak. This is the same mineral, sodium

hexafluoroaluminate, that is crushed and sold to grape growers as

cryolite although now it is widely produced synthetically by combining

sodium, fluoride, and aluminum.

It

is difficult to gauge the fluoride content of raisins following the

introduction of cryolite to grape crops around 1970 — the same year the

government realized the need to establish an Environmental Protection

Agency — but my investigator instincts tell me there was more going on

than government regulators were able (or perhaps willing) to monitor.

Here was my first clue.

You

might not remember this but on Thursday, August 7, 1997, while you were

celebrating the completion of the mapping of human chromosome 7 and

pleading “quit playing games (with my heart),” the EPA published a notice

to inform you of the filing of a pesticide petition to amend the

established tolerances for fluoride residue on certain food crops. Remember?

The

petition was submitted by the Cryolite Task Force which is comprised of

two cryolite manufacturers, Elf Atochem North America and Gowan

Company.

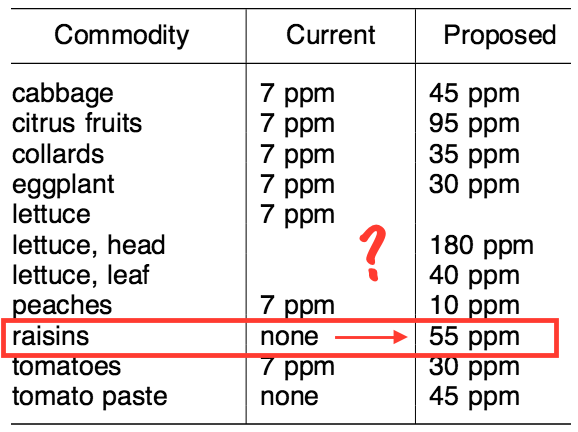

Previously,

there was a blanket fluoride tolerance for approved crops at 7 ppm.

There was no established fluoride tolerance specifically for raisins but

the Cryolite Task Force proactively asked for one to be set at 55 ppm.

Why would they do that?

A tolerance for raisins was the only new

tolerance they requested, except for tomato paste which they asked to

be established due to their proposed increase in the existing tomato

tolerance (don’t even get me started on the tomato mafia).

Granted,

it is easy to see where the Cryolite Task Force was coming from when

they asked for the limit for fluoride in raisins to be set at 55 ppm.

Fifty-five is a fine Fibonacci, triangular, semiprime, square pyramidal

number. So why not.

Also, children and dogs should be responsible for thoroughly washing and peeling their raisins before eating them anyway.

Internet might try to convince

you 55 ppm is the current limit for fluoride in raisins, but that’s

because she likes to mess with you sometimes. When I tried to force her

to get serious, she just kinda shrugged her shoulders and mumbled

“idunno.” It was weird. For grapes, the tolerance for cryolite is 7

ppm. But what about raisins? The current guidelines don’t say. You can

review the EPA tolerances for cryolite yourself here.

I

thought perhaps EPA just lumped raisins in with grapes, but that is not

the case with tolerances for other pesticides where they are listed

separately. Grapes are grapes and raisins are raisins. The government is

very clear with their food definitions. If the EPA makes a point of

telling us that “onion” refers to both bulb onions and green onions and

that “sweet potatoes” are also yams, then surely they would have told us

if “grapes” are also raisins but only if cryolite is involved.

Maybe

the EPA does not have a current tolerance for fluoride residue from

cryolite on raisins because raisin crops are no longer treated with

cryolite?

The only study I could find regarding the elevated fluoride content of raisins was published in 1997 by researchers at the University of Kansas who measured raisins containing fluoride at 5.2 ppm.

I

offered Internet a chance to redeem herself by asking, “Is cryolite

still used on raisin crops in California?” She escorted me into the land

of the California Department of Pesticide Regulation’s (CDPR) online reporting database. It is a strange new world in there, with incredible sites to behold.

In the most recent Summary of Pesticide Use Data,

the CDPR describes cryolite as one of a few “widely applied

insecticides” commonly used in the state. In 2013, cryolite was ranked

at number 37 on the top 100 countdown of most used pesticides in California with over five hundred thousand pounds applied to California farmland. Over half of that total was used on vineyards.

Out

of the 289,700 pounds of cryolite used in 2013 on California grapes,

288,700 pounds were sprayed on grape crops in the self-described raisin

capital of the world, San Joaquin Valley.

California’s

pesticide reporting database does not differentiate between raisins and

table grapes (the industry term for the grapes you buy at the grocery

store). As a result, it is unclear what percentage of the half a million

pounds of cryolite used in California in 2013 were applied to raisin

crops. But we know cryolite is applied to raisins. Why else would they

use so much of it on vineyards in San Joaquin Valley?

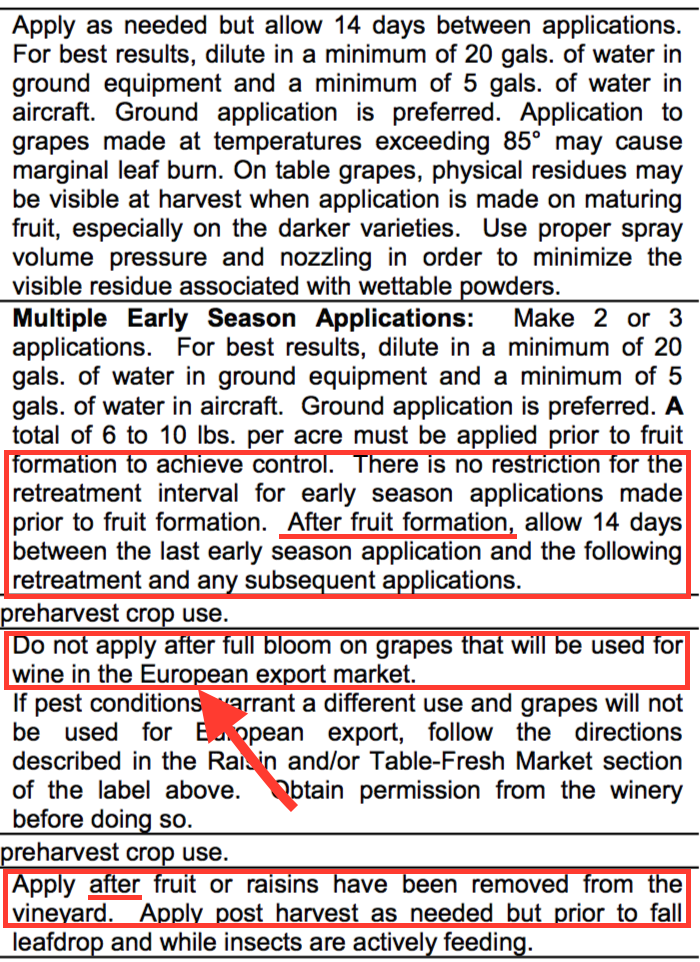

But here’s another clue. The manufacturer includes instructions for applying cryolite to raisin crops on the label.

In

case you ever find yourself in a position where you need to apply

cryolite to raisin crops, hypothetically speaking of course (wink,

wink), here is how you do it.

If

you are spraying it from the ground, you need to dilute it in 20

gallons of water but if you are spraying it from an airplane and

planning to fly away real quick, you only need to dilute it with 5

gallons of water. Just don’t let anyone over three inches tall near the

sprayed area for at least 12 hours.

You

can reapply cryolite without restriction unless the grapes are already

formed in which case, just like with swimming after lunch, you should

wait two weeks between applications just to be on the safe side.

The

label goes on to read, “Do not apply after full bloom on grapes that

will be used for wine in the European export market. If you are only

serving wine to dumb Americans, or raisins to their children, go ahead

and dump a bunch more cryolite on them.”

You

can apply cryolite post-harvest as needed but only after the fruit has

been removed from the vineyard. As the label states, “Whatever you do, DO NOT apply cryolite while raisins are drying for three weeks on the cryolite-laden ground next to vines doused in cryolite. No reason. Just don’t, okay?”

Grapeleaf

Skeletonizers and Omnivorous Leafrollers can require anywhere from 3 to

10 pounds of cryolite per acre per application to be effective, but

don’t apply more than 20 pounds per acre per season pre-harvest.

I

don’t know about you, but I find the instructions for applying cryolite

are a lot to remember and I can see how it might be misapplied from

time to time.

That

got me wondering who monitors and enforces all these pesticide

regulations. It’s all well and good to have strict tolerances for

pesticide residue, but is that like a strict Taliban rule, e.g. “steal

this apple and I’ll chop of your hand?” Or is it more like a strict

librarian rule, e.g. “bring back this book or I’ll fine you 5 cents per

day?”

As it turns out, it’s neither.

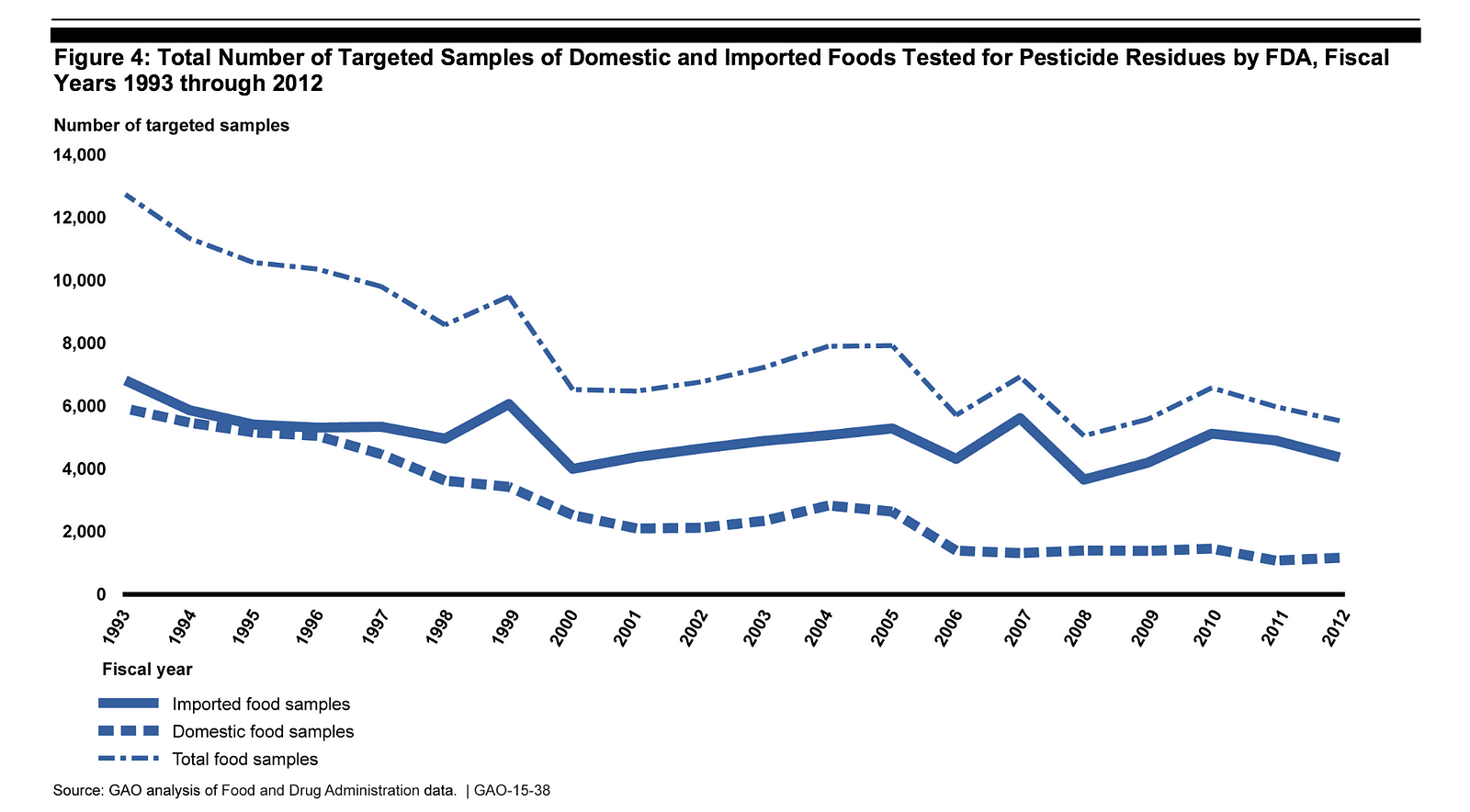

The

EPA is only responsible for establishing the tolerances for pesticide

residue. The monitoring and enforcement aspect is left to the Food and

Drug Administration and the Department of Agriculture.

According to the most recent annual summary report for the FDA’s pesticide monitoring program, the FDA uses measuring methods that detect 484 pesticides. Cryolite is not on the list.

In an attempt to give FDA the benefit of the doubt, I went through the trouble of sorting through their Glossary of Pesticide Chemicals which lists alternative names for over 1,000 pesticides. None of those names for cryolite are on the list either.

That can’t be right, can it?

Cryolite

is the third most used pesticide on the second most productive crop in

the number one agricultural producing state in the country. Why is the

FDA not monitoring for it?

When

government regulators reviewed the safety studies on cryolite, even

though most of the information considered in the review process is

derived from unpublished, non-peer-reviewed studies carried out by the

chemical companies themselves (as is the style), the EPA still saw the

need for a blanket tolerance for approved food crops at 7 ppm.

But why bother establishing a pesticide tolerance if no one is going to enforce it?

Thinking

I must be missing something, I then went through the actual databases

that list each domestic food item FDA food inspectors sampled for

pesticides throughout the year. Since this article is turning into quite

the science thriller, I will now recreate the scene for you when I

first searched the FDA’s most recent pesticide residue database for domestically produced food items.

It

was 4 am and I couldn’t sleep because I had that nagging feeling

(again) that the raisin mafia was up to no good. That’s when I

downloaded the file (US2012.zip).

Picture

a spreadsheet with 57,502 rows. Each row lists a food item, the type of

pesticide it was inspected for, the number of samples tested, the

percent that tested positive, the average amount of pesticide each

positive sample contained, etc. Now picture me using the handy ctrl+f

search feature (if you don’t know it, learn it, you’ll love it) to look

for the word raisin. Now picture me making a Taylor Swift surprise face.

But not a good surprise. There were no search results for raisins.

According

to the online FDA database for domestic food products, the FDA did not

inspect a single raisin for a single pesticide in 2012, the year of the

most recent data posted online. Domestic Craisins, raisins’ sworn

archenemy, were inspected for 380 different pesticides, but there was

not one test listed for pesticide residue on the undefeated dried fruit

champion of the American food scene.

I checked other years and the results were similar. In 2011,

they tested one lonely American raisin and he happened to be clean of

the chemicals they checked for, but as we suspected earlier, cryolite

was not on the list. In 2010, they inspected another American raisin for a panel of non-cryolite chemicals but he was clean too (hid ’em in his Converse).

Imported

raisins are a different story. In 2012, the FDA inspected raisins

imported from Afghanistan, Argentina, Canada, Chile, China, and South

Africa. But the U.S. only imports a minuscule portion of the 220,000

tons of raisins consumed by Americans each year. Why is the FDA focused

on inspecting raisins imported from Canada and neglecting California

raisins? And how did they even find raisins imported from Canada? That’s

like looking for a Craisin in a raisin bunker.

The

Department of Agriculture also monitors food items for pesticide

residue although they are more focused on gathering information to

determine the total pesticide load on children rather than enforcing EPA

regulations. They partner with state labs to conduct the actual

testing. The California Department of Pesticide Regulation posts these reports online, too.

The state labs were doing pretty good remembering to test raisins in the late ’80s, but in the ’90s they only remembered once

(1995). Between 1996 and 2014, they only tested raisins two more times

including in 2010 when they looked at a raisin for pyrethrins, an

organic compound derived from chrysanthemums, and in 2012 when they did a

general pesticide screen (cryolite not included) on two more raisins.

To

give you an idea of how strange this is, in an average year, let’s go

with 2011, the California Department of Pesticide Regulation tested for

pesticide residue on 24 jicama, 23 chayote, 6 watercress, 3 water

chestnuts, and zero raisins.

According to their sampling history database, they inspect other common

fruit and vegetables like oranges, eggplant, cantaloupe, garlic,

raspberries, etc. every year. But raisins for the most part have had a

free pass.

Could that have anything to do with the government-sanctioned raisin mafia or the five billion dollars

California vineyards bring in as revenue each year? That’s more money

than any other food crop in California except almonds (don’t even get me

started on the almond mafia).

I

don’t know why California stopped routinely inspecting raisins for

pesticides in 1989 but I do know this: the country that produces half

the world’s raisin supply from one monocrop outside of Fresno barely

monitors them for pesticides.

III. Raisins and Fluoridated Wine

Speaking

of 1989, the year California stopped routinely inspecting raisins,

this happened to be the same year wine-sniffing Europeans noticed

excessive amounts of fluoride in the California wine they were

importing.

European

regulators attempted to set a limit for fluoride of 1 ppm but Cryolite

manufacturer Elf Atochem North America, along with Gowan Company, Gallo

Winery, the Wine Institute, and California State University Fresno, argued for an exception of up to 3 ppm for California vineyards that use cryolite.

This amount of fluoride is 50 percent higher than the Maximum Secondary

Contaminant Level set by the EPA for drinking water and over four times

higher than the CDC’s current recommendation for fluoridated water.

The request was approved and yet some California vineyards treated with cryolite still failed to meet the 3 ppm exception.

According to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation, the use of cryolite on wine grapes in 2013

was confined to five counties: Fresno, Kings, Tulare, Madera, and Kern

(plus one vineyard used by a large producer of inexpensive table wine in

Yolo county). These counties are all located in Southern San Joaquin

Valley, the raisin capital of the world.

Northern

vineyards, including those in Napa and Sonoma, do not use cryolite.

Neither do vineyards in southern or coastal areas like Temecula or

Monterey.

To confirm, I contacted every regional winery and growers association

in California outside San Joaquin Valley and asked about their use of

cryolite. The ones who replied either never heard of cryolite or

verified they do not use it on their vineyards. I was also told that

because cryolite is a fluoride product, some agricultural chemical

companies like Wilbur Ellis won’t sell it because of possible problems

with residual fluoride in the groundwater. Vineyards in Oregon and Washington states are not treated with cryolite, either.

Studies of grape juice confirm an elevated fluoride content in some grapes. When researchers from Tufts University measured the fluoride level in 43 ready-to-drink fruit juices, they found the highest amount of fluoride in grape juice from Gerber at 6.8 ppm, well above the EPA’s maximum contaminant level for fluoridated water of 4 ppm.

In 2002, a cryolite manufacturer petitioned the National Organic Standards Board to

have cryolite included on the list of allowed pesticides for organic

production, relying on the longstanding dental argument that “as a

mineral, the only residues remaining are basic elements found in

nature.”

As far as I can tell, the petition was not approved.

(However this 2014 Pesticide Use Report from the California Department of Pesticide Regulation states that cryolie is allowed

on organic crops. I called them to inquire about it and after bouncing

me around to a bunch of offices, they decided it was just a typo… hmm….)

IV. Raisins and Dogs

In

1989, the year California stopped routinely inspecting raisins for

pesticides and the year Europeans noticed high amounts of fluoride in

imported wine from California, this also happened to be the year ASPCA’s Animal Poison Control Center noted the beginning of a trend in dogs

like McGee who confiscated cartons of raisins from their live-in house

servants. Within hours, the dogs developed vomiting, diarrhea, and in

some cases, lethal kidney failure.

These are all symptoms of acute fluoride poisoning, people.

In

the 1990s, while California pesticide regulators were busy inspecting

rutabaga, celeriac and cherimoya, raisin toxicity in dogs continued to

be reported in cases throughout the country and across a variety of

brands consumed, which should not have been surprising considering

virtually all raisins in the United States, regardless of brand, are

produced from the same monocrop.

ASPCA veterinarians claim pesticides are an “unlikely” cause of raisin toxicity in dogs,

but it is a proven medical fact that healthcare professionals in the

United States have a blindspot to the adverse health effects of

fluoride. Let’s take a closer look at their research before accepting

the idea that although humans have been cohabiting with dogs for

centuries, veterinarians suddenly noticed in 1989 that raisins (and

sometimes grapes) are intrinsically toxic to canines.

In a 2005 study published in the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine,

veterinary toxicologists from the ASPCA’s Animal Poison Control Center

conducted a retrospective analysis of 43 cases of acute renal failure in

dogs following the ingestion of raisins and grapes. The earliest case

report included in the study was from 1992.

(By the way, in 1992, California raisin growers dropped over two million pounds of cryolite on their raisin crops.)

In

13 of the cases, Labrador retrievers played the leading role of raisin

thief with 19 other breeds making up the remainder. Only 23 of the

dogs survived their grape/raisin snack, and 8 of the surviving dogs

experienced long-term side effects.

Veterinarians

think of themselves as dog specialists so they focused on the dog part

of the story which explains why most of the retrospective study is an

intensely close and personal look at dog pee. But now that you’ve read

my raisin saga, I think it’s safe to say that you and I are armchair

raisin specialists. So we are going to focus on the raisins.

Of

the 43 dogs in the study, 28 ingested raisins, 13 ingested grapes, and 2

ingested both. In one case, the study states “the raisins were

described as organic.” The grapes the dogs consumed included regular

table grapes, wine grapes, and grapes grown from vines on the owners’

property. (Did these vineyards happen to be located in the

self-described raisin-capitol of the world? The study doesn’t say.)

The

dosage of raisins the dogs consumed ranged anywhere from 2.8 to 19.6

grams per kilogram of body weight. The veterinary toxicologists found

this odd. Generally, when a substance is toxic, the more of it you

consume, the more likely you are to become sick. But a lot of dogs

consume raisins and never become sick. Some big dogs die from a

relatively small dose of raisins while some small dogs die only after

eating a large dose of raisins. Other dogs eat raisins all the time

without incident, until suddenly one day there’s an incident.

The ASPCA researchers hypothesize this might

be due to an extrinsic substance that is not always present on raisins

but they claim pesticides are an unlikely culprit because any pesticide

residue would not contain high enough concentrations to cause renal

failure.

What

evidence do they provide to support this claim? The authors point to

FDA inspections of domestic table grapes (not raisins) in 2002 in which

20 samples of the six million tons of California grapes produced that

year were found to be perfectly safe.

Of course you and I know those samples weren’t even tested for residue from the millions of pounds of cryolite dumped over California.

They also claim that pesticides rarely accumulate on grapes, citing this study of grapes in Sardinia… But Sardinia is in Italy, not Fresno where all of our raisins come from!

The

other evidence the ASPCA veterinarians cite was from one of the dog

case studies where the offending raisins were tested for chlorinated

hydrocarbon, carbamate, and organo-phosphorus insecticides. If even a

single Raisin 101 class was

taught in the school system these days, they would have known to test

for fluoride too, but because veterinarians are raisin-illiterate, the

opportunity was wasted.

This is how worldwide rumors get started.

The ASPCA’s analysis of raisin poisoning in dogs was cited in Google Scholar by 42 other articles. To give an example of how this grapevine works, one of those articles

was published by the Veterinary Poisons Information Service in London

which includes an insightful chart to show the upward trend of raisin

toxicity in recent years. The author notes raisin toxicity is a new

thing but he reasons it was probably just misdiagnosed before, as if

past veterinarians wouldn’t have been able to put together the clues of a

guilty-looking dog, an empty carton of raisins, and raisin-sprinkled

vomit less than 24 hours later.

Researchers in Canada, South Korea, Sweden, Austria, Germany

and throughout the United States also reference the ASPCA study.

California raisins are consumed in all of these regions but no one

bothered to look up what pesticides are used the most on California

raisin crops, let alone hire a lab to test for them.

If

you are anything like me, you are probably pretty worked up at this

point. I have so many browser windows, spreadsheets, and text files open

that I can’t find my email, I’ve texted my husband about nothing but

raisins for the past seven days, I literally greeted my coworker this

morning by saying “Good Raisin,” and every time I see a veterinarian’s

face I feel like yelling, “get your head out of the dog’s crotch and

look at the dang dancing raisins.”

The story of fluoride and raisins is important because 1) it is killing dogs all over the world and 2) if a single box of the wrong kind of raisin can kill a Labrador retriever, what can it do to a human being?

“But Melissa, raisin toxicity isn’t a trend in humans.”

Let’s

just think this through for a moment. Dogs don’t usually eat raisins.

When they do, it’s often because they confiscated an illicit food item.

Labrador retrievers are particularly notorious for this because they

have figured out that the secret to life, happiness, and everything is

the more you eat, the more you can retrieve and the more you retrieve,

the more you eat. When dogs vomit, it’s almost always because they got

into something they shouldn’t have, and it’s usually not difficult to

figure out what it was (stupid human obsession with stupid food packaging).

But

when children vomit, or just get indigestion or an upset stomach, why

would anyone ever suspect the cause to be the box of raisins they ate

with lunch? Or a glass of grape juice? You would probably just think

they caught a virus that’s going around.

I’m not saying that children get sick from eating raisins covered in pesticide. I am saying that if

children get sick from eating raisins covered in pesticide, I am not

confident any of us would have been able to figure that one out yet.

Veterinarians

still haven’t figured out cryolite is the cause of raisin toxicity in

dogs and they had the culprit vomited to them on a silver platter.

V. Raisins and Dentists (and Bureaucrats)

I

admit, the story of fluoride and raisins is difficult to swallow. You

might be wondering how it’s even possible. When did we fall down a

raisin chute and end up in Willy Wonka’s Mad Hatter Raisin Factory? I

might be mixing my Johnny Depp metaphors here but you know what I mean.

Could the EPA, the FDA, the USDA, and the entire state of California all

be conspiring on such an expansive plot?

Here’s

how this works. It’s not that our government is full of evil

bureaucrats who congregate in cubicles, plotting ways to poison the rest

of the population and the planet. I observed government workers in

their native habitat long enough to know this is not the norm.

But

let’s do a quick behavioral profile assessment on government employees

for a moment, shall we? Most of them are good people, even dentists, and

they just want to show up, get the job done (with minimal effort, let’s

be honest), and go home to their families — just like the rest of us.

Government

bureaucrats tend to be more risk-averse than your average American

entrepreneur, which explains what attracted them to the stability of a

government job in the first place. This trait, along with their

propensity to use Microsoft Word’s cut and paste feature (or until very

recently, WordPerfect), means the status quo is almost always favored.

Why rewrite the wheel when you can submit the same old wheel everyone

else has been wheeling since 1945.

Rewriting wheels is risky business, and government bureaucrats a) don’t do risk and b) don’t do business. They do bureaucracy.

It is statistically probable that outright corruption goes on from time to time. Have you

ever tried to refuse an offer from the raisin mafia? But in my

experience here in the United States, bad things happen mainly because

bureaucrats are just normal people behaving as normal people tend to

behave, with a few rotten raisins thrown in the mix.

To

give an example, let’s conclude our raisin chronicle with an account of

the government’s efforts to approve cryolite and establish the

associated residue tolerances.

Cryolite

was first approved in 1957 when federal officials responded to the

manufacturer’s request for registration in a formal letter stating,

“Golly gee, Mr. Business Man, that sounds like a mighty fine idea,

almost as good as the ones we heard last week about putting lead in

paint to make the colors prettier and putting air pollution in water to make our teeth stronger. You Business Men sure are a clever bunch. Yours truly, Mr. G. Man.”

By

the mid-1980s, cryolite had been an approved pesticide for over 25

years and yet EPA evaluators admitted their database for cryolite was “extremely poor” with “extensive data gaps” in all disciplines.

The

EPA reregistered cryolite in 1996 but at that point, the pesticide was a

40-year incumbent. That’s a lot of quo for a government bureaucrat to

overcome. And this wasn’t your generic “we always do it this way” brand

of status quo. By 1996, cryolite had a rare vintage of hyper quo that

pesticides like DDT never dreamed was possible.

This is where we see the fingerprints of our story’s biggest villains, despite their careful use of latex gloves.

Since

cryolite is basically just ground fluoride minerals, the EPA treats it

as fluoride. As a result, all the work dentists did over the past

century to try to prove that fluoride added to the water supply is “safe

and effective” was used to vouch for the safety of cryolite, too.

Dentists did not do this work on their own. Just like in the official story of fluoridation on the NIDCR website, they worked with corporations who had a vested interest in proving that fluoride is both safe and effective.

One

of the most common elements in the earth’s crust, fluoride is also the

most reactive. Because of its high reactivity, fluoride is not found on

its own in nature but is bound with common metals and minerals such as

bauxite and phosphate. In addition, fluoride has the prized ability of

lowering the melting point of metals, making it a bedrock of key

manufacturing processes. This explains why fluoride is a byproduct of so

many industries, from aluminum plants and phosphate processors, to

steel mills, coal burning operations, and brick and tile manufacturers.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture,

“Airborne fluorides have caused more worldwide damage to domestic

animals than any other air pollutant.” To avoid future litigation, when

dentists started investigating fluoride, corporations were all too

willing to work closely with them to keep an eye on the science and help

direct their research. They desperately needed a way to clear

fluoride’s name.

In

1913, Alcoa leaders took this strategy a step further when they created

the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research at the University of

Pittsburgh. Alcoa-funded researchers at the Mellon Institute were the first to make a public proposal to add fluoride to the water supply.

Similarly,

the Kettering Laboratory of Applied Physiology at the University of

Cincinnati was established in 1930 by other corporations with a

self-interest in fluoride research, including DuPont and General Motors.

By 1931, the majority of the Kettering Laboratory’s research focused on

fluoride. Kettering scientists spent their careers refuting studies

that revealed the dangers of fluoride exposure. When their own studies

indicated fluoride is toxic, such as the one they conducted in 1958 on

42 beagle dogs, the results were never published and were literally hidden in the basement.

Undue

industry influence on government dental research, combined with

institutional and bureaucratic pressure to maintain the status quo,

reveals why the health hazards of fluoride are not apparent to

regulators.

The

EPA evaluators who reregistered cryolite readily admit it accumulates

in the body at all doses, but they don’t consider that a bad thing.

Dental fluorosis (the brown stains on teeth McKay studied in Colorado)

is noted as “an endpoint” in several toxicology studies but that’s also

ruled out as an adverse affect.

When one of the studies in EPA’s review

suggested that “severe maternal toxicity” occurred at lower cryolite

doses, the EPA evaluators simply deemed the study unacceptable. Their

justification was copied and pasted directly from a government review on

fluoridated water that said ingestion of fluoride at current levels “should have no adverse effects on human reproduction.” (Emphasis added because really?)

Also during the reregistration process, EPA evaluators reviewed a 2-year study conducted by the National Toxicology Program that found evidence of carcinogenicity in male rats. But again this information was glossed over with a simple quote from a previous fluoridation review that stated, “the available laboratory data are insufficient to demonstrate a carcinogenic effect of fluoride in animals.”

Now

to my ears, that sounds like we haven’t done sufficient studies on the

cancer-causing effects of fluoride and that maybe we should do some

before we sprinkle fluoride flakes (a.k.a. raisins) on our kids’

breakfast cereal, but the EPA evaluators for cryolite interpreted it

differently.

I know this is how we deal with people accused of murder, but are pesticides innocent until proven guilty, too?

(FYI, in 1992, a chief toxicologist at EPA’s Office of Drinking Water was fired when he raised concerns over the carcinogenicity of fluoride. He was reinstated under the Whistleblower Protection Act but his concerns about the safety of fluoride were never addressed.)

One of the other studies

the EPA used to evaluate the safety of cryolite was from Battelle

Laboratory who was tasked with conducting a dermal study on baby Easter

Bunnies to gauge the safety of cryolite when it comes into contact with

the skin.

When

several “diva” bunnies died after licking their fur, an act that was

not in their contract, EPA told Battelle they didn’t need a do-over

because it was already obvious to them just by looking at the picture of

cryolite that it would not be absorbed through the skin to an

appreciable extent to justify requiring an additional study.

Despite

the “extreme sensitivity of the rabbit to oral doses of cryolite,” the

EPA went on to approve the use of cryolite on the food we feed our

children, our dogs, and occasionally our rabbits (see Exhibit B).

If

EPA evaluators stopped staring at paper and computer screens and

instead started examining actual cryolite and the people who are exposed

to it, then perhaps its toxicity would become apparent to them.

In

1932, without access to computers, biased industry studies, or dental

rumors of any kind, researchers at the State Hospital in Copenhagen

published the first comprehensive report of industrial cryolite toxicity

after studying 78 workers from a cryolite factory who developed lung

fibrosis, fluorosis of bones and ligaments, and gastrointestinal

problems attributed to their exposure to fluoride. When their workspace

was especially dusty, they experienced routine bouts of nausea and

vomiting, too.

In contrast, to check the box next to farm worker safety, EPA evaluators looked through their official records for incidents involving cryolite since 2002.

When no results were found, they concluded, “Golly gee, Mr. Business

Men, you sure are good at taking care of your migrant work force. Looks

like there’s no rush on that inhalation toxicity study we’ve been meaning to get around to for 60 years. Please let us know if you poison any of your workers in the future. Yours truly, Mr. G. Man.”

Raisin

harvesting is commonly recognized as the most labor intensive activity

in American agriculture, requiring an extra 40,000 to 50,000 workers for

a three- or four-week harvest period each year. In a 1991 survey, 35 percent of raisin harvesters readily admitted they used fraudulent documents to obtain employment in the United States. A recent article in the Economist

cites that statistic as high as 90 percent for today’s seasonal raisin

work force. Is it surprising none of them filed an incident report for

pesticide exposure in the federal database?

If

the EPA evaluators would have at least asked Internet about it, they

would have noticed a handful of cryolite illness reports filed by the

California Department of Pesticide Regulation, including a 2009 incident

when a school bus driver saw three students run across the street to

avoid cryolite spray. The children were interviewed and reported

symptoms of headache, nausea, dizziness, and sore throat. Pesticide

drift was confirmed by foliage samples.

Yet

not a single incident involving cryolite and farm laborers has been

reported in the federal database in the last decade. Doesn’t that seem a

little suspicious, EPA? Maybe it’s time to get your head out of the

computer’s crotch and look at the raisin-pickin’ raisin pickers.

The

EPA reregistration for cryolite in 1996 did explain one mystery: why

the Cryolite Task Force submitted a petition one year later for a

residue tolerance for fluoride on raisins of 55 ppm.

The EPA report notes that fluorine compounds in raisins are concentrated ten times higher than the residue on grapes.

Since the tolerance for grapes was 7 ppm, EPA evaluators simply

submitted a request to EPA’s Mathematics Department to multiply that

number by ten to calculate a proposed tolerance for raisins of 70 ppm.

EPA ruled favorably on that amount but then realized it did not conform

to the government procedure for calculating such tolerances which

required the use of maximum averages rather than average maximums so

they settled on the fine Fibonacci number of 55 instead.

Despite the petition from the Cryolite Task Force, an EPA document from 2011

states the modified tolerances for cryolite from 1996 were not

published, and as I mentioned previously, the current residue tolerance

for raisins is not listed on the latest EPA guideline.

We

could go mad hatter crazy researching the EPA paper trail for cryolite

tolerances, but we already wasted enough raisin jokes on their

antics — you and I and every raisin grower this side of Willy Wonka’s

Raisin Factory already know they’re not enforced or even monitored.

The government knows it, too.

In a 2014 report to Congress, the Government Accountability Office criticized the FDA for scrutinizing imported foods over domestic crops,

even though most of the food items consumed in the United States are

produced domestically. They also chastised FDA for not disclosing in

its annual report that inspectors do not monitor for several common pesticides with established residue tolerances.

It

is not surprising that cryolite is one of the pesticides FDA deems

unworthy of their time. Even the EPA, the agency that established the

tolerance, has stated,

“Food contributes only small amounts of fluoride and monitoring the

diet for fluoride intake is not very useful for current public health

concerns.”

Our

government bureaucrats — just like the rest of us — have been

brainwashed by dentists and biased industry scientists for decades into

believing that fluoride is nothing more than a natural mineral that

makes our teeth stronger. It is safe and effective. Safe and effective.

Safe and effective…

So

that’s the long version of how to keep your dentist from killing your

Labrador retriever (and other pets). If you want the short version, buy

organic.

No comments:

Post a Comment