Zionism, Crypto-Judaism, and the Biblical Hoax

Laurent Guyénot • April 8, 2019 •What’s a neocon, Dad? from the Unz Review

“What’s

a neocon?” clueless George W. Bush once asked his father in 2003. “Do

you want names, or a description?” answered Bush 41. “Description.”

“Well,” said 41, “I’ll give it to you in one word: Israel.” True or not,

that exchange quoted by Andrew Cockburn[1]

sums it up: the neoconservatives

are crypto-Israelis. Their true

loyalty goes to Israel — Israel as defined by their mentor Leo Strauss

in his 1962 lecture “Why We Remain Jews,” that is, including an indispensable Diaspora.[2]

In his volume Cultural Insurrections, Kevin

MacDonald has accurately described neoconservatism as “a complex

interlocking professional and family network centered around Jewish

publicists and organizers flexibly deployed to recruit the sympathies of

both Jews and non-Jews in harnessing the wealth and power of the United

States in the service of Israel.”[3] The proof of the neocons’ crypto-Israelism is their U.S. foreign policy:

“The confluence of their interests as Jews in promoting the policies of the Israeli right wing and their construction of American interests allows them to submerge or even deny the relevance of their Jewish identity while posing as American patriots. […] Indeed, since neoconservative Zionism of the Likud Party variety is well known for promoting a confrontation between the United States and the entire Muslim world, their policy recommendations best fit a pattern of loyalty to their ethnic group, not to America.”[4]

The

neocons’ U.S. foreign policy has always coincided with the best interest

of Israel as they see it. Before 1967, Israel’s interest rested heavily

on Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe. From 1967, when Moscow

closed Jewish emigration to protest Israel’s annexation of Arab

territories, Israel’s interest included the U.S. winning the Cold War.

That is when the editorial board of Commentary, the monthly magazine of the American Jewish Committee, experienced their conversion to “neoconservatism,” and Commentary became,

in the words of Benjamin Balint, “the contentious magazine that

transformed the Jewish left into the neoconservative right .”[5]

Irving Kristol explained to the American Jewish Congress in 1973 why

anti-war activism was no longer good for Israel: “it is now an interest

of the Jews to have a large and powerful military establishment in the

United States. […] American Jews who care about the survival of the

state of Israel have to say, no, we don’t want to cut the military

budget, it is important to keep that military budget big, so that we can

defend Israel.”[6]

This tells us what “reality” Kristol was referring to, when he famously

defined a neoconservative as “a liberal who has been mugged by reality”

(Neoconservatism: the Autobiography of an Idea, 1995).

With

the end of the Cold War, the national interest of Israel changed once

again. The primary objective became the destruction of Israel’s enemies

in the Middle East by dragging the U.S. into a third world war. The

neoconservatives underwent their second conversion, from anti-communist

Cold Warriors to Islamophobic “Clashers of Civilizations” and crusaders

in the “War on Terror.”

In September 2001, they got the “New Pearl Harbor” that they had been wishing for in a PNAC report a year before.[7]

Two dozens neoconservatives had by then been introduced by Dick Cheney

into key positions, including Richard Perle, Paul Wolfowitz and Douglas

Feith at the Pentagon, David Wurmser at the State Department, and Philip

Zelikow and Elliott Abrams at the National Security Council. Abrams had

written three years earlier that Diaspora Jews “are to stand apart from

the nation in which they live. It is the very nature of being Jewish to

be apart — except in Israel — from the rest of the population.”[8] Perle, Feith and Wurmser had co-signed in 1996 a secret Israeli report entitled A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm,

urging Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to break with the Oslo Accords

of 1993 and reaffirm Israel’s right of preemption on Arab territories.

They also argued for the overthrow of Saddam Hussein as “an important

Israeli strategic objective in its own right.” As Patrick Buchanan

famously remarked, the 2003 Iraq war proves that the plan “has now been

imposed by Perle, Feith, Wurmser & Co. on the United States.”[9]

How

these neocon artists managed to bully Secretary of State Colin Powell

into submission is unclear, but, according to his biographer Karen

DeYoung, Powell privately rallied against this “separate little

government” composed of “Wolfowitz, Libby, Feith, and Feith’s ‘Gestapo

Office’.”[10] His chief of staff, Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, declared in 2006

on PBS that he had “participated in a hoax on the American people, the

international community and the United Nations Security Council,”[11]

and in 2011, he openly denounced the duplicity of neoconservatives such

as Wurmser and Feith, whom he considered “card-carrying members of the

Likud party.” “I often wondered,” he said, “if their primary allegiance

was to their own country or to Israel.”[12]

Something doesn’t quite ring true when neocons say “we Americans,” for

example Paul Wolfowitz declaring: “Since September 11th, we Americans have one thing more in common with Israelis.”[13]

The

neocons’ capacity to deceive the American public by posturing as

American rather than Israeli patriots required that their Jewishness be

taboo, and Carl Bernstein, though a Jew himself, provoked a scandal by

citing on national television the responsibility of “Jewish neocons” for the Iraq war.[14]

But the fact that the destruction of Iraq was carried out on behalf of

Israel is now widely accepted, thanks in particular to the 2007 book by

John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy.

And even the best liars betray themselves sometimes. Philip Zelikow

briefly dropped the mask during a conference at the University of

Virginia on September 10, 2002:

“Why would Iraq attack America or use nuclear weapons against us? I’ll tell you what I think the real threat is and actually has been since 1990: it’s the threat against Israel. And this is the threat that dare not speak its name, because the Europeans don’t care deeply about that threat, I will tell you frankly. And the American government doesn’t want to lean too hard on it rhetorically, because it is not a popular sell.”[15]

From crypto-Judaism to crypto-Zionism

Norman Podhoretz, editor-in-chief of Commentary (and father-in-law of Elliott Abrams), said that after June 1967, Israel became “the religion of the American Jews.”[16]

That is, at least, what he started working at. But, naturally, such

religion had better remain discreet outside the Jewish community, if

possible even secret, and disguised as American patriotism. The neocons

have perfected this fake American patriotism wholly profitable to

Israel, and ultimately disastrous for Americans — a pseudo-Americanism

that is really a crypto-Israelism or crypto-Zionism.

This

quasi-religious crypto-Zionism is comparable to the crypto-Judaism that

has played a determining role in Christendom in the late Middle Ages.

From the end of the 14th century, sermons, threats of expulsion, and

opportunism made over a hundred thousand Jewish converts to Catholicism

in Spain and Portugal, many of whom continued to “Judaize” secretly.

Freed from the restrictions imposed on Jews, these “New Christians,”

called Conversos or Marranos, experienced a meteoric socio-economic ascension. In the words of historian of Marranism Yirmiyahu Yovel:

“Conversos rushed into Christian society and infiltrated most of its interstices. After one or two generations, they were in the councils of Castile and Aragon, exercising the functions of royal counselors and administrators, commanding the army and navy, and occupying all ecclesiastical offices from parish priest to bishop and cardinal. […] The Conversos were priests and soldiers, politicians and professors, judges and theologians, writers, poets and legal advisors—and of course, as in the past, doctors, accountants and high-flying merchants. Some allied themselves by marriage to the greatest families of Spanish nobility […] Their ascent and penetration in society were of astonishing magnitude and speed.”[17]

Not all these Conversos were

crypto-Jews, that is, insincere Christians, but most remained proudly

ethnic Jews, and continued to marry among themselves. Solomon Halevi,

chief rabbi of Burgos, converted in 1390, took the name of Pablo de

Santa Maria, became Bishop of Burgos in 1416, and was succeeded by his

son Alonso Cartagena. Both father and son saw no contradiction between

the Torah and the Gospel, and believed that Jews made better Christians,

as being from the chosen people and of the race of the Messiah.[18]

A new situation was created after the Alhambra Decree (1492)

that forced Spanish Jews to choose between conversion and expulsion.

Four years later, those who had stayed loyal to their faith and migrated

to Portugal were given the choice between conversion and death, with no

possibility of leaving the country. Portugal now had a population of

about 12 percent so-called New Christians, deeply resentful of

Catholicism. They learned and perfected the art of leading a double

life. When they were eventually allowed to leave the country and engage

in international trade in 1507, they “soon began to rise to the

forefront of international trade, virtually monopolizing the market for

certain commodities, such as sugar, to participate to a lesser degree in

trading spices, rare woods, tea, coffee, and the transportation of

slaves.”[19]

When in 1540, the new Portuguese king introduced the Inquisition

following the Spanish model, tracking down Portuguese Judaizers all over

Europe and even in the New World, Marranos became more intensely

resentful of the Catholic faith they had to fake, and more secretive.

They would play an important role in the Calvinist or Puritan movement

which, after undermining Spanish domination on the Netherlands,

conquered England and ultimately formed the religious bedrock of the

United States.

Catholic

monarchs are to blame for having drafted by force into Christendom an

army of enemies that would largely contribute to the ruin of the

Catholic empire. By and large, the Roman Church has done much to foster

the Jewish culture of crypsis. However, segregation and forced

conversions were not the only factor. Crypto-Jews could find

justification in their Hebrew Bible, in which they read:

“Rebekah took her elder son Esau’s best clothes, which she had at home, and dressed her younger son Jacob in them. […] Jacob said to his father, ‘I am Esau your first-born’” (Genesis 27:15–19).

If

Jacob cheated his brother Esau of his birthright by impersonating him,

why would they not do the same (Jacob being, of course, Israel, and Esau

or Edom being codenames for the Catholic Church among medieval Jews)?

Crypto-Jews also found comfort and justification in the biblical figure

of Esther, the clandestine Jewess who, in the Persian king’s bed,

inclined him favorably toward her people. For generations, Spanish and

Portuguese Marranos prayed to “saint Esther.”[20]

This is significant because the legend of Esther is a cornerstone of

Jewish culture: every year the Jews celebrate its happy ending (the

massacre of 75,000 Persians by the Jews) by the feast of Purim.[21]

Another factor to consider is the ritual prayer of Kol Nidre recited

before Yom Kippur at least since the 12th century, by which Jews

absolved themselves in advance of “all vows, obligations, oaths or

anathemas, pledges of all names,” including, of course, baptism .

Marranos

and their descendants had a deep and lasting influence in economic,

cultural and political world history, and their culture of crypsis

survived the Inquisition. A case in point is the family of Benjamin

Disraeli, Queen Victoria’s prime minister from 1868 to 1869, and again

from 1874 to 1880, who defined himself as “Anglican of Jewish race.”[22]

His grandfather was born from Portuguese Marranos converted back to

Judaism in Venice, and had moved to London in 1748. Benjamin’s father,

Isaac D’Israeli was the author of a book on The Genius of Judaism,

but had his whole family baptized when Benjamin was thirteen, because

administrative careers were then closed to the Jews in England.

Benjamin

Disraeli has been called the true inventor of British imperialism, for

having Queen Victoria proclaimed Empress of India in 1876. He

orchestrated the British takeover of the Suez Canal in 1875, thanks to

funding from his friend Lionel Rothschild (an operation that also

consolidated the Rothschilds’ control over the Bank of England). But

Disraeli can also be considered a major forerunner of Zionism; well

before Theodor Herzl, he tried to introduce the “restoration of Israel”

into the Berlin Congress agenda, hoping to convince the Ottoman Sultan

to concede Palestine as an autonomous province.

What

was Disraeli’s motivation behind his British imperial foreign policy?

Did he believe in Britain’s destiny to control the Middle East? Or did

he see the British Empire as the tool for the fulfillment of Israel’s

own destiny? In mooring the Suez Canal to British interests, did he just

seek to outdo the French, or was he laying the foundation for the

future alliance between Israel and the Anglo-American Empire? No one can

answer these questions with certainty. But Disraeli’s contemporaries

pondered them. William Gladstone, his longtime competitor for the prime

ministry, accused him of “holding British foreign policy hostage to his

Jewish sympathies.”[23]

So we see that the neoconservatives’ loyalty to Israel, and their

control of the Empire’s foreign policy, is not a new issue. The case of

Disraeli highlights the legacy between pre-modern crypto-Judaism and

modern crypto-Zionism.

The dialectic of nation and religion

From

his Darwinian perspective, Kevin MacDonald sees crypto-Judaism as “an

authentic case of crypsis quite analogous to cases of mimetic camouflage

in the natural world.”[24]

But Judaism itself, in its modern form, falls into the same category,

according to MacDonald. In the 18th century, by claiming to be adepts of

a religious confession, Jews gained full citizenship in European

nations, while remaining ethnically endogamic and suspiciously

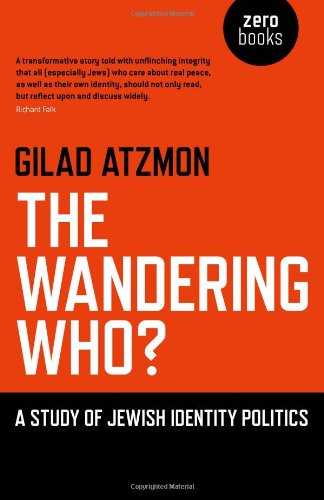

uninterested in converting anyone. Gilad Atzmon points out that the

Haskalah motto, “Be a Jew at home and a man in the street” is

fundamentally dishonest:

“The Haskalah Jew is deceiving his or her God when at home, and misleading the goy once in the street. In fact, it is this duality of tribalism and universalism that is at the very heart of the collective secular Jewish identity. This duality has never been properly resolved.”[25]

Zionism was an attempt to resolve it. Moses Hess wrote in his influential book Rome and Jerusalem (1862):

“Those of our brethren who, for purposes of obtaining emancipation, endeavor to persuade themselves, as well as others, that modern Jews possess no trace of a national feeling, have really lost their heads.”

For him, a Jew is a Jew “by virtue of his racial origin, even though his ancestors may have become apostates.”[26]

Addressing his fellow Jews, Hess defended the national character of

Judaism and denounced the assimilationist Jew’s “beautiful phrases about

humanity and enlightenment which he employs as a cloak to hide his

treason.”[27]

In

return, Reformed Judaism opposed the nationalist version of Jewishness

which would become Zionism. On the occasion of their 1885 Pittsburgh

Conference, American reformed rabbis issued the following statement:

“We consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religion community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor the restoration of a sacrificial worship under the Sons of Aaron, or of any of the laws concerning the Jewish State.”[28]

Yet

Reformed Judaism promoted a messianic theory that continued to ascribe

an exalted role to Israel as chosen people, nation or race.

German-American rabbi Kaufmann Kohler, a star of the Pittsburgh

Conference, argued in his Jewish Theology (1918) for the

recycling of the messianic hope into “the belief that Israel, the

suffering Messiah of the centuries, shall at the end of days become the

triumphant Messiah of the nations.”

“Israel is the champion of the Lord, chosen to battle and suffer for the supreme values of mankind, for freedom and justice, truth and humanity; the man of woe and grief, whose blood is to fertilize the soil with the seeds of righteousness and love for mankind. […] Accordingly, modern Judaism proclaims more insistently than ever that the Jewish people is the Servant of the Lord, the suffering Messiah of the nations, who offered his life as an atoning sacrifice for humanity and furnished his blood as the cement with which to build the divine kingdom of truth and justice.”[29]

It

is easy to recognize here an imitation of Christianity: the crucifixion

of Christ (by the Jews, as Christians used to say) is turned into a

symbol of the martyrdom of the Jews (by Christians). Interestingly, the

theme of the “crucifixion of the Jews” was also widely used by secular Zionist Jews as a diplomatic argument.

But

what is more important to understand is that Reformed Judaism rejected

traditional nationalism (the quest for statehood) only to profess a

superior, metaphysical kind of nationalism. In this way, Reformed

Judaism and Zionism, while affirming their mutual incompatibility and

competing for the hearts of Jews, dovetailed perfectly: Zionism played

the rhetoric of European nationalist movements to claim “a nation like

others” (for Israelis), while Reformed Judaism aimed at empowering a nation like no other and without borders (for Israelites).

That explains why in 1976, American Reformed rabbis crafted a new

resolution affirming: “The State of Israel and the Diaspora, in fruitful

dialogue, can show how a People transcends nationalism while affirming

it, thus establishing an example for humanity.”[30]

In a marvelous example of Hegelian dialectical synthesis, both the

religious and the national faces of Jewishness contributed to the end

result: a nation with both a national territory and an international

citizenry, exactly what Leo Strauss had in mind. Except for a few

orthodox Jews, most Jews today see no contradiction between Judaism as a

religion and Zionism as a nationalist project.

The

question of whether such dialectical machinery was engineered by Yahweh

or by B’nai B’rith is open to debate. But it can be seen as an inherent

dynamic of Jewishness: the Jewish cognitive elites may find themselves

divided on many issues, but since their choices are ultimately

subordinated to the great metaphysical question, “Is it good for Jews?” there always comes a point when their oppositions are resolved in a way that reinforces their global position.

With

“what is good for the Jews” in mind, contradictions are easily

resolved. Jewish intellectuals, for example, can be ethnic nationalists

in Israel, and pro-immigration multiculturalists everywhere else. A

paragon of this contradiction was Israel Zangwill, the successful author

of the play The Melting Pot (1908), whose title has become a

metaphor for American society, and whose Jewish hero makes himself the

bard of assimilation by mixed marriages: “America is God’s Crucible, the

great Melting-Pot where all the races of Europe are melting and

reforming.” The paradox is that when he was writing this, Zangwill was a

leading figure of Zionism, that is, a movement affirming the

impossibility of Jews living among Gentiles, and demanding that they be

ethnically separated. (Zangwill is the author of another famous formula:

“Palestine is a land without people for a people without land.”)

Although

it appears to be contradictory for non-Jews, this dual standard is not

necessarily so from the point of view of Jewish intellectuals. They may

sincerely believe in their universalistic message addressed to the

Goyim, while simultaneously believing sincerely that Jews should remain a

separate people. The implicit logic is that it is good that Jews remain

Jews in order to teach the rest of mankind to be universal, tolerant,

anti-racists, immigrationnists, and caring for minorities (specially

Jews). This logic falls under the “mission theory”, the secular version

of the “messianic nation” theory: Jews, who have invented monotheism,

the Ten Commandments and so on, have a moral obligation to keep

educating the rest of humankind. What the “mission” entails is open to

reversible interpretations. Rabbi Daniel Gordis, in Does the World Need Jews? claims that “Jews need to be different in order that they might play a quasi-subversive role in society [. . .] the goal is to be a contributing and respectful ‘thorn in the side’ of society.”[31]

That naturally tends to upset the Goyim, but it is for their good. It

is to free them from their “false gods” that Jews are “a corrosive

force”, also insists Douglas Rushkoff, author of Nothing Sacred: The Truth About Judaism.

Preaching

universalism to the Goyim in the street while emphasizing ethnic

nationalism at home is the great deception. It is the essence of

crypto-Judaism and of its modern form, crypto-Zionism. It is so deeply

ingrained that it has become a kind of collective instinct among many

Jews. It can be observed in many situations. The following remark by

historian Daniel Lindenberg illustrates that Jewish internationalists’

relation to Israel in the 20th century strongly resembled the Marranos’

relation to Judaism in pre-modern times:

“Anyone who has known Communist Jews, ex-Kominternists, or even some prominent representatives of the 1968 generation will know what frustrated crypto-Jewishness means: Here are men and women who, in principle, according to the ‘internationalist’ dogma, have stifled in themselves all traces of ‘particularism’ and ‘petty-bourgeois Jewish chauvinism,’ who are nauseated by Zionism, support Arab nationalism and the great Soviet Union—yet who secretly rejoice in Israel’s military victories, tell anti-Soviet jokes, and weep while listening to a Yiddish song. This goes on until the day when, like a Leopold Trepper, they can bring out their repressed Jewishness, sometimes becoming, like the Marranos of the past, the most intransigent of neophytes.”[32]

Zion and the New World Order

If

Jews can be alternatively or even simultaneously nationalists (Zionists)

and internationalists (communists, globalists, etc.), it is, in the

last analysis, because this duality is inherent to the paradoxical

nature of Israel. Let us not forget that until the foundation of the

“Jewish state”, “Israel” was a common designation for the international

Jewish community, for example when on March 24, 1933, the British Daily Express printed on its front-page: “The whole of Israel throughout the world is united in declaring an economic and financial war on Germany.”[33]

Until 1947, most American and European Jews were satisfied of being

“Israelites”, members of a worldwide Israel. They saw the advantage of

being a nation dispersed among nations. International Jewish

organizations such as B’nai B’rith (Hebrew for “Children of the

Covenant”) founded in New York in 1843, or the Alliance Israélite

Universelle, founded in Paris in 1860, had no claim on Palestine.

Even

after 1947, most American Jews remained ambivalent about the new State

of Israel, knowing perfectly well that to support it would make them

vulnerable to the accusation of dual loyalty. It was only after the

Six-Day War that American Jews began to support Israel more actively and

openly. There were two reasons for this. First, Zionist control of the

press had become such that American public opinion was easily persuaded

that Israel had been the victim and not the aggressor in the war that

led Israel to triple its territory. Secondly, after 1967, the crushing

deployment of Israeli power against Egypt, a nation supported

diplomatically by the USSR, enabled the Johnson administration to

elevate Israel to a strategic asset in the Cold War. Norman Finkelstein

explains:

“For American Jewish elites, Israel’s subordination to US power was a windfall. Jews now stood on the front lines defending America—indeed, ‘Western civilization’—against the retrograde Arab hordes. Whereas before 1967 Israel conjured the bogey of dual loyalty, it now connoted super-loyalty. […] After the 1967 war, Israel’s military élan could be celebrated because its guns pointed in the right direction—against America’s enemies. Its martial prowess might even facilitate entry into the inner sanctums of American power.”[34]

Israeli

leaders, for their part, stopped blaming American Jews for not settling

in Israel, and recognized the legitimacy of serving Israel while

residing in the United States. In very revealing terms, Benjamin

Ginsberg writes that already in the 1950s, “an accommodation was reached

between the Jewish state in Israel and the Jewish state in America”;

but it was after 1967 that the compromise became a consensus, as

anti-Zionist Jews were marginalized and silenced.[35]

Thus was born a new Israel, whose capital was no longer only Tel Aviv

but also New York; a transatlantic Israel, a nation without borders,

delocalized. It was not really a novelty, but rather a new balance

between two inseparable realities: the international Diaspora of

Israelites, and the national State of Israelis.

Thanks

to this powerful diaspora of virtual Israelis now entrenched in all

levels of power in the US, France and many other nations, Israel is a

very special nation indeed. And everyone can see that it has no

intention of being an ordinary nation. Israel is destined to be an

Empire. If Zionism is defined as the movement for the foundation of a

Jewish State in Palestine, then what we see at work today may be called

meta-Zionism, or super-Zionism. But there is no real need for such a new

term, for Zionism, in fact, had always been about a new world order,

under the mask of “nationalism”.

David

Ben-Gurion, the “father of the nation”, was a firm believer in the

mission theory, declaring: “I believe in our moral and intellectual

superiority, in our capacity to serve as a model for the redemption of

the human race.”[36] In a statement published in the magazine Look on January 16, 1962, he predicted for the next 25 years:

“All armies will be abolished, and there will be no more wars. In Jerusalem, the United Nations (a truly United Nations) will build a Shrine of the Prophets to serve the federated union of all continents; this will be the seat of the Supreme Court of Mankind, to settle all controversies among the federated continents, as prophesied by Isaiah.”[37]

That

vision was passed on to the next generation. In October 2003, the

highly symbolic King David Hotel hosted a “Jerusalem Summit”, whose

participants comprised three acting Israeli ministers, including

Benjamin Netanyahu, and Richard Perle as guest of honor. They signed a

declaration that recognized Jerusalem’s “special authority to become a

center of world’s unity,” and professed:

“We believe that one of the objectives of Israel’s divinely-inspired rebirth is to make it the center of the new unity of the nations, which will lead to an era of peace and prosperity, foretold by the Prophets.”[38]

Zionists and the Bible

Both

Ben-Gurion’s prophecy and the Jerusalem Declaration highlight the fact

that Zionism is an international project based on the Bible. That

Zionism is biblical doesn’t mean it is religious; to Zionists, the Bible

is both a “national narrative” and a geopolitical program rather than a

religious book (there is actually no word for “religion” in ancient

Hebrew). Ben-Gurion was not religious; he never went to the synagogue

and ate pork for breakfast. Yet he was intensely biblical. Dan Kurzman,

who calls him “the personification of the Zionist dream,” titles each

chapter of his biography (Ben-Gurion, Prophet of Fire, 1983) with a Bible quote. The preface begins like this:

“The life of David Ben-Gurion is more than the story of an extraordinary man. It is the story of a biblical prophecy, an eternal dream. […] Ben-Gurion was, in a modern sense, Moses, Joshua, Isaiah, a messiah who felt he was destined to create an exemplary Jewish state, a ‘light unto the nations’ that would help to redeem all mankind.”

For

Ben-Gurion, writes Kurzman, the rebirth of Israel in 1948 “paralleled

the Exodus from Egypt, the conquest of the land by Joshua, the Maccabean

revolt.” Ben-Gurion himself emphasized: “There can be no worthwhile

political or military education about Israel without profound knowledge

of the Bible.”[39]

Ten days after declaring Israel’s independence, he wrote in his diary :

“We will break Transjordan [Jordan], bomb Amman and destroy its army,

and then Syria falls, and if Egypt will still continue to fight—we will

bombard Port Said, Alexandria and Cairo.” Then he adds: “This will be in

revenge for what they (the Egyptians, the Aramis and Assyrians) did to

our forefathers during biblical times.”[40]

Can you be more biblical than that ? Ben-Gurion was in no way a special

case. His infatuation with the Bible was shared by almost every Zionist

leader of his generation and the next. Moshe Dayan, the military hero

of the Six-Day War, wrote a book entitled Living with the Bible (1978)

in which he biblically justified Israel’s annexation of Arab

territories. Naftali Bennet, Israeli minister of Education, has also

recently justified the annexation of the West Bank by the Bible.

Christian

will say that Zionists don’t read their Bible correctly. Obviously,

they don’t read it with the pink Christian glasses. In Isaiah, for

example, Christians find hope that, one day, people “will hammer their

swords into plowshares and their spears into sickles” (Isaiah 2:4). But

Zionists correctly start with the previous verses, which describe these

messianic times as a Pax Judaica, when “all the nations” will pay

tribute “to the mountain of Yahweh, to the house of the god of Jacob,”

when “the Law will issue from Zion and the word of Yahweh from

Jerusalem,” so that Yahweh will “judge between the nations and arbitrate

between many peoples.” Further down in the same book, they read:

“The riches of the sea will flow to you, the wealth of the nations come to you” (60:5); “For the nation and kingdom that will not serve you will perish, and the nations will be utterly destroyed” (60:12); “You will suck the milk of nations, you will suck the wealth of kings” (60:16); “You will feed on the wealth of nations, you will supplant them in their glory” (61:5-6);

Zionism

cannot be a nationalist movement like other, because it resonates with

the destiny of Israel as outlined in the Bible: “Yahweh your God will

raise you higher than every other nation in the world” (Deuteronomy

28:1). Only by taking into account the biblical roots of Zionism can one

understand that Zionism has always carried within it a hidden

imperialist agenda. It may be true that Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau

sincerely wished Israel to be “a nation like others,” as Gilad Atzmon

explains.[41]

But still, when they called their movement “Zionism”, they used

Jerusalem’s biblical name borrowed from the most imperialistic

prophecies, and most notably Isaiah 2:3 quoted above.

Biblical

prophecies outline Israel’s ultimate destiny, or meta-Zionism, whereas

the historical books, and particularly the Book of Joshua, set the

pattern for the first stage, the conquest of Palestine, or Zionism. As

wrote Avigail Abarbanel in “Why I left the Cult,” the Zionist conquerors

of Palestine “have been following quite closely the biblical dictate to

Joshua to just walk in and take everything. […] For a supposedly

non-religious movement it’s extraordinary how closely Zionism […] has

followed the Bible.”[42] In the same mood, Kim Chernin writes:

“I can’t count the number of times I read the story of Joshua as a tale of our people coming into their rightful possession of their promised land without stopping to say to myself, ‘but this is a history of rape, plunder, slaughter, invasion, and destruction of other peoples.’”[43]

A

“history of genocide” would not be exaggerated, if we consider the

treatment reserved to Canaanites: In Jericho, “They enforced the curse

of destruction on everyone in the city: men and women, young and old,

including the oxen, the sheep and the donkeys, slaughtering them all”

(Joshua 6:21). The city of Ai met the same fate. Its inhabitants were

all slaughtered, twelve thousand of them, “until not one was left alive

and none to flee. […] When Israel had finished killing all the

inhabitants of Ai in the open ground, and in the desert where they had

pursued them, and when every single one had fallen to the sword, all

Israel returned to Ai and slaughtered its remaining population”

(8:22–25). Women were not spared. “For booty, Israel took only the

cattle and the spoils of this town” (8:27). Then came to turn of the

cities of Makkedah, Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron, Debir, and Hazor. In

the whole land, Joshua “left not one survivor and put every living

thing under the curse of destruction, as Yahweh, god of Israel, had

commanded” (10:40).

It

certainly helps to understand the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians

to know that the Book of Joshua is considered a glorious chapter of

Israel’s national narrative. And when Israeli leaders claim that their

vision of the global future is based on the Hebrew Bible, we should take

them seriously and study the Bible. It is helpful, for example, to be

aware that Yahweh has designated to Israel “seven nations greater and

mightier than you,” that “you must utterly destroy,” and “show no mercy

to them.” As for their kings, “you shall make their name perish from

under heaven” (Deuteronomy 7:1-2, 24). The destruction of the “Seven

Nations,” also mentioned in Joshua 24:11, is considered a mitzvah in rabbinic Judaism, and by the great Maimonides in his Book of Commandments,[44]

and it has remained a popular motif in Jewish culture. Knowing this

will help to understand the neocon agenda for World War IV (as Norman

Podhoretz names the current global conflict).[45]

General Wesley Clark, former Supreme Commander for NATO in Europe (he

led the NATO agression against Serbia twenty years ago), wrote, and repeated in numerous occasions,

that one month after September 11, 2001, a Pentagon general showed him a

memo “that describes how we’re gonna take out seven countries in five

years, starting with Iraq, and then Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia and

Sudan and finishing off with Iran.”[46] Wesley Clark has managed to pass as a whistleblower, but I believe he belongs to what Gilad Atzmon sees as the Jewish controlled opposition, together with Amy Goodman of Democracy Now who interviewed him.[47] Only in 1999 has he revealed being the son of Benjamin Jacob Kanne

and the proud descendant of a lineage of Kohen rabbis. It is hard to

believe that he has never heard about the Bible’s “seven nations”. Is

Clark a crypto-Zionist trying to write history in biblical terms, while

blaming these wars on WASP Pentagon warmongers? Interestingly, in his

September 20, 2001 speech, President Bush also cited seven “rogue

states” for their support of global terrorism, but in his list, Cuba and

North Korea replaced Lebanon and Somalia. It is because part of Bush’s

entourage refused to include Lebanon and Somalia, while his neocon

handlers insisted on keeping the number seven for its symbolic value?

Whatever the explanation, I suspect that the importance of targeting

exactly “seven nations” after 9/11 stems from the same biblical

obsession as the need to have ten Nazis hanged on Purim day 1946 to

match the ten sons of Haman hanged in the Book of Esther. Just like Rabbi Bernhard Rosenberg can now marvel at how prophetic the Book of Esther is,[48]

the idea is to “realize,” a few decades from now, that World War IV

fulfilled Deuteronomy 7: the destruction of Israel’s seven enemy

nations. Christian Zionists will be in extasy and praise “the Lord” (as

their Bible translates YHWH). Of course, fulfilling prophecies does not

always come easy: Isaiah 17:1, “Behold, Damascus will soon cease to be a

city, it will become a heap of ruins,” is not quite done, yet.

The Solomon hoax

I believe that Gilad Atzmon is making a very important point when emphasizing:

“Israel defines itself as the Jewish state. In order to grasp Israel, its politics, its policies and the intrusive nature of its lobby, we must understand the nature of Jewishness.”

And

I believe that Jewishness is, at the core, the ideology of the Tanakh.

There was no Jewishness before the Tanakh, and the Tanakh is the single

ultimate root connecting all expressions of Jewishness, whether

religious or secular—for what that distinction is worth. Jewishness

would simply wither without the Tanakh.

Zionism

is an expression of Jewishness. As we have seen, it is inherently

imperialistic because it is biblical. I will now argue that it is also

inherently deceptive because it is biblical. There are two aspects to

the deceptive nature of the Tanakh: historical and metaphysical. To

understand them, we need to know the context of its writing. The

greatest part of the Tanakh, including the historical books, was edited

during the exilic period, and reached its near-final form after Babylon

had fallen under Persian rule in 539 BCE. That thesis, first put forward

by Baruch Spinoza in 1670,[49]

has always met with fierce opposition from the Christian world, but it

was accepted by the great British historian of civilizations Arnold J.

Toynbee,[50] and it is now getting the high ground.[51]

The Judean exiles, after having helped the Persians conquer Babylon,

were rewarded by high offices at the Persian court, and obtained the

right to return to Jerusalem and set up a government subject to Persia.

The manner by which these Judeo-Babylonian Levites maneuvered the

Persians’ imperial policy in support of their theocratic project for

Palestine is unknown, but we can imagine it similar to the way the

Zionists have hijacked the Anglo-American empire’s foreign policy in

recent times; the edict of Cyrus the Great presented at the beginning of

the Book of Ezra is comparable to the Balfour Declaration. In 458 BCE,

eighty years after the return of the first exiles, Ezra, proud

descendant of a line of Aaronite priests, went from Babylon to

Jerusalem, mandated by the king of Persia and accompanied by some 1,500

followers. He was soon joined by Nehemiah, a Persian court official of

Judean origin. As “Secretary of the Law,” Ezra carried with him the

newly redacted Torah, and Spinoza plausibly suggested that he was the

head of the scribal school that had compiled and edited most of the

Tanakh.

The

history of Israel and Judea that we have today was written as

justification for that proto-Zionist enterprise, which implied the

usurpation of the name and heritage of the ancient kingdom of Israel by

the Judeans. Of course, not everything in the historical books is pure

invention: ancient materials were used, but the main narrative that

aggregates them is built on a post-exilic ideological construct. The

central piece of that narrative is the glorious kingdom of Solomon,

reaching from the Euphrates to the Nile (1Kings 5:1), with its

magnificent temple and its lavish royal palace in Jerusalem (described

in detail in 1Kings 5-8). Solomon had “seven hundred wives of royal rank

and three hundred concubines” (11:3) and “received gifts from all the

kings in the world, who had heard of his wisdom” (5:14). We know today

that Solomon’s kingdom is a complete fabrication, a mythical past

projected as the mirror image of a desired future, a fictitious

justification for the prophecy of its “restoration”. Even the idea that

Jerusalem, located in Judea, was once the capital of Israel is blatantly

false: Israel never had any other capital than Samaria.

Twentieth-century archeology has definitively exposed the fallacy: there

is no trace whatsoever of Solomon and his “united kingdom”.[52]

The

scam is quite evident from the way the authors of the Books of Kings,

aware of the absolute baselessness of their story, back it with the

grotesque testimony of a totally spurious Queen of Sheba:

“The report I heard in my own country about your wisdom in handling your affairs was true then! Until I came and saw for myself, I did not believe the reports, but clearly I was told less than half: for wisdom and prosperity, you surpass what was reported to me. How fortunate your wives are! How fortunate these courtiers of yours, continually in attendance on you and listening to your wisdom! Blessed be Yahweh your God who has shown you his favour by setting you on the throne of Israel! Because of Yahweh’s everlasting love for Israel, he has made you king to administer law and justice.” (1 Kings 10:6-9)[53]

When

Ben-Gurion declared before the Knesset three days after invading the

Sinai in 1956, that what was at stake was “the restoration of the

kingdom of David and Solomon,”[54]

and when Israeli leaders continue to dream of a “Greater Israel” of

biblical proportions, they are simply perpetuating a

two-thousand-year-old deception—self-deception perhaps, but deception

all the same.

Deeper

than the historical deception, at the very core of the Bible, lies a

more essential metaphysical deception which goes a long way towards

explaining the ambivalence of tribalism and universalism so typical of

Jewishness. Biblical historian Philip Davies wrote that “the ideological structure of the biblical literature can only be explained in the last analysis as a product of the Persian period,”[55]

and the central idea of that “ideological structure” is biblical

monotheism. In the pre-exilic strata of the Bible, Yahweh is a national

god among others: “For all peoples go forward, each in the name of its

god, while we go forward in the name of Yahweh our god for ever and

ever,” says pre-exilic prophet Micah (4:5). What sets Yahweh apart from

other national gods is his jealousy, which supposes the existence of

other gods: “You shall have no other gods to rival me” (Exodus 20:3).

Only in the Persian period does Yahweh really become the only existing

God, and, by logical consequence, the creator of the Universe—Genesis 1

being demonstrably taken from Mesopotamian myths.

That

transformation of national Yahweh into the “God of heaven and earth” is

a case of crypsis, an imitation of Persian religion, for the purpose of

political and cultural ascendency. The Persians were predominantly

monotheistic under the Achaemenids, worshipers of the Supreme God Ahura

Mazda, whose representations and invocations can be seen on royal

inscriptions. Herodotus—who, by the way, travelled through

Syria-Palestine around 450 BCE without hearing about Jews—wrote about

the Persians’ customs:

“they have no images of the gods, no temples nor altars, and consider the use of them a sign of folly. [….] Their wont, however, is to ascend the summits of the loftiest mountains, and there to offer sacrifice to Zeus, which is the name they give to the whole circuit of the firmament.” (Histories, I.131)

Persian

monotheism was remarkably tolerant of other cults. In contrast, Judean

monotheism is exclusivist because, although Yahweh now claims to be the

universal God, he remains the ethnocentric, jealous god of Israel. And

so Persian influence was not the only factor in the development of

biblical monotheism, that is, the claim that “the god of Israel” is the

One and Only God: Yahweh’s sociopathic jealousy, his murderous hatred of

all other gods and goddesses, was an important ingredient from

pre-exilic times: being the only god worthy of worship is tantamount to

being the only god, and therefore God. In 1Kings 18, we see Yahweh

compete with the great Syrian Baal Shamem (“Lord of Heaven”) for

the title of True God, by means of a holocaust contest ending with the

slaughter of four hundred prophets of Baal. Later on we read of the

Judean general Jehu who, having overthrown and slaughtered Israel’s

dynasty of King Omri, summoned all the priests of Baal for “a great

sacrifice to Baal,” and, as sacrifice, massacred them all. “Thus Jehu

rid Israel of Baal” (2Kings 10,18-28). This informs us on how Yahweh

supposedly became Supreme God instead of Baal: by the physical

elimination of all the priests of Baal, that is, exactly the same way

that Jehu became king of Israel by exterminating the family of the

legitimate king, as well as “all his leading men, his close friends, his

priests; he did not leave a single one alive” (2Kings 10:11).

Yet

these legendary stories have come to us in a post-exilic redaction, and

although they may reflect an earlier competition between Yahweh and

Baal, the metaphysical claim that Yahweh is the supreme God, the Creator

of Heaven and Earth, only became an explicit creed and a cornerstone of

Judaism from the Persian period. It was a means of

assimilation-dissimulation into the Persian commonwealth, comparable to

the way Reformed Judaism mimicked Christianity in the 19th century.

The Book of Ezra and the prostitute of Jericho

The

process of how Yahweh was transformed from national to universal god,

while remaining intensely chauvinistic, can actually be documented from

the Book of Ezra. It contains extracts from several edicts attributed to

succeeding Persian kings. All are fake, but their content is indicative

of the politico-religious strategy deployed by the Judean exiles for

their proto-Zionist lobbying. In the first edict, Cyrus the Great

declares that “Yahweh, the God of Heaven, has given me all the

kingdoms of the earth and has appointed me to build him a Temple in

Jerusalem,” then goes on to allow “his [Yahweh’s] people to “go up to

Jerusalem, in Judah, and build the Temple of Yahweh, the god of Israel, who is the god in Jerusalem”

(Ezra 1:2–3). We understand that both phrases refer to the same entity,

but the duality is significant. We find the same paradoxical

designation of Yahweh as both “God of Heaven” and “god of Israel in

Jerusalem” in the Persian edict authorizing the second wave of return.

It is now King Artaxerxes who asks “the priest Ezra, Secretary of the

Law of the God of Heaven,” to offer a gigantic holocaust to “the god of Israel who resides in Jerusalem” (7:12-15). We later find twice the same expression “God of Heaven” (Elah Shemaiya)

interspersed with seven references to “your god,” that is, “the god of

Israel” (keep in mind that capitalization is irrelevant here, being a

convention of modern translators). “God of Heaven” appears one more time

in the book of Ezra, and it is, again, in an edict signed by the

Persian king: Darius confirms Cyrus’s edict and recommends that the

Israelites “offer sacrifices acceptable to the God of Heaven and

pray for the life of the king and his sons” (6:10). Everywhere else the

book of Ezra only refers to the “god of Israel” (four times), “Yahweh,

the god of your fathers” (once), and “our god” (ten times). In other

words, according to the author of the book of Ezra, only the kings of

Persia imagine that Yahweh is “the God of Heaven”—a common title of the

universal Ahura Mazda—while for the Jews, Yahweh is merely their god,

the “god of Israel,” the god of their fathers, in short, a national god.

Indeed, imperial authorities are told that the Jerusalem Temple is

dedicated to the God of Heaven, although the idea seems irrelevant to

the Judeans themselves: when the Judeans are challenged the right to

(re)build their temple by the local Persian governor, they tell him: “We

are the servants of the God of Heaven and Earth” (5:11) and refer to

Cyrus’s edict. And when Nehemiah wants to convince the Persian king let

him go to Judea to oversee the rebuilding of Jerusalem, he offers a

prayer “to the God of Heaven” (Nehemiah 2:4); but once in Jerusalem, he

asks his fellow Jews to swear allegiance to “Yahweh our god” (10:30).

This

unmistakable pattern in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah may be taken as a

clue of the deepest secret of Judaism, and a key to understanding the

real nature of “Jewish universalism”: for the Jews, Yahweh is the god of

the Jews, whereas Gentiles must be told that he is the supreme and only

God. “In the heart of any pious Jew, God is a Jew,” writes Maurice

Samuel in You Gentiles (1924), while to Gentiles, Yahweh must be presented as the universal God who happens to prefer Jews.[56]

The pattern is repeated in the book of Daniel when Nebuchadnezzar,

impressed by Daniel’s oracle, prostrates himself and exclaims: “Your god

is indeed the God of gods, the Master of kings” (Daniel 2:47).

The

hypothesis that the dual nature of Yahweh (god of Israel for the Jews,

God of the Universe for Gentiles) was intentionally encrypted into the

Hebrew Bible becomes more plausible when we find the same pattern in the

Book of Joshua. The book was probably written before the Exile,

possibly under king Josiah (639-609 BCE). Its original author never

refers to Yahweh simply as “God,” and never implies that he is anything

but “the god of Israel” (9:18, 13:14, 13:33, 14:14, 22:16). Even Yahweh

calls himself “the god of Israel” (7:13). When Joshua speaks to the

Israelites, he speaks of “Yahweh your god” (1:11, 1:12, 1:15, 3:3, 3:9,

4:5, 4:23-24, 8:7, 22:3-4, 22:5, 23:3,5,8,11, 24:2). The Israelites

collectively refer to “Yahweh our god” (22:19), or individually as

“Yahweh my god” (14:8). Israel’s enemies speak to Joshua about “Yahweh

your god” (9:9), and he tells them about “Yahweh my god” (9:23). Yahweh

is once called “lord of the whole earth” by Joshua (3:13), and once “the

god of gods” by enthusiastic Israelites (22:22), but none of this can

be considered to contain any explicit theological claim that Yahweh is

the Creator: it is more like the Persian king calling himself king of

kings and ruler of the world. Neither can the mention of an altar built

by the Israelites as “a witness between us that Yahweh is god” (22:34)

be taken to mean anything more than “Yahweh is god between us.” If the

Yahwist scribe of the Book of Joshua had believed Yahweh to be the

universal God, he would have written of whole cities being converted

rather than exterminated for the glory of Yahweh.

The

only explicit profession of faith that Yahweh is the supreme God, in

the whole Book of Joshua, is coming from a foreigner, just like in the

books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Not a king, this time, but a prostitute.

Rahab is a prostitute in Jericho, who infiltrates the invading

Israelites into the city. As justification for betraying her own people,

she tells the Israelites that “Yahweh your god is God both in Heaven

above and on Earth beneath” (2:11), something that neither the narrator,

nor Yahweh, nor any Israelite in the book ever claims. Rahab’s

profession of faith is likely to be a post-exilic addition to the book,

for it actually conflicts with her more prosaic motivation:

“we are afraid of you and everyone living in this country has been seized with terror at your approach. […] give me a sure sign of this: that you will spare the lives of my father and mother, my brothers and sisters and all who belong to them, and will preserve us from death.” (2:9-12).

In

the final redaction, the pattern is the same as in the Book of Ezra, and

reveals the secret of post-exilic Judaism: To the Jews, Yahweh is their

national god, but it is good for the Jews that Gentiles (whether kings

or prostitutes) regard Yahweh as the “God of Heaven”. It has worked

wonderfully: Christians today believe that the God of humankind decided

to manifest himself as the jealous “god of Israel” from the time of

Moses, whereas the real historical process is the reverse: it is the

tribal “god of Israel” who impersonated the God of humankind at the time

of Ezra—while continuing to prefer Jews.

Worshipping

a national god with imperialistic ambitions, while pretending to the

Gentiles that they are worshipping the One True God, is manufacturing a

catastrophic misunderstanding. A public scandal emerged in 167 CE, when

the Hellenistic emperor Antiochos IV dedicated the temple in Jerusalem

to Zeus Olympios, the Greek name of the supreme God. He had been led to

understand that Yahweh and Zeus were two names for the same cosmic God,

the Heavenly Father of all mankind. But the Jewish Maccabees who led the

rebellion knew better: Yahweh may be the Supreme God, but only Jews are

intimate with Him, and any way the Pagans worship Him is an

abomination. Moreover, although the Israelites claimed that their Temple

was dedicated to the God of all mankind, they also firmly believed that

any non-Jew entering it should be put to death. This fact alone betrays

the true nature of Hebrew monotheism: it was a deception from the

beginning, the ultimate metaphysical crypsis. Only when that biblical

hoax is exposed to the world will Zion start to lose its symbolic power.

For it is the original source of the psychopathic bond by which Israel

controls the world.

Notes

[1] Andrew Cockburn, Rumsfeld: His Rise, His fall, and Catastrophic Legacy, Scribner, 2011, p. 219. Cockburn claims to have heard this repeated by “friends of the family.”

[2] Leo Strauss, “Why we Remain Jews”, quoted in Shadia Drury, Leo Strauss and the American Right, St. Martin’s Press, 1999 (on archive.org), p. 31-43.

[3] Kevin MacDonald, Cultural Insurrections: Essays on Western Civilizations, Jewish Influence, and Anti-Semitism, The Occidental Press, 2007, p. 122.

[4] Kevin McDonald, Cultural Insurrection, op. cit., p. 66.

[5] Benjamin Balint, Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine That Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right, Public Affairs, 2010.

[6] Congress Bi-Weekly, quoted by Philip Weiss, “30 Years Ago, Neocons Were More Candid About Their Israel-Centered Views,” Mondoweiss.net, May 23, 2007: mondoweiss.net/2007/05/30_years_ago_ne.html

[8] Elliott Abrams, Faith or Fear: How Jews Can Survive in a Christian America, Simon & Schuster, 1997, p. 181.

[9]

Patrick J. Buchanan, “Whose War? A neoconservative clique seeks to

ensnare our country in a series of wars that are not in America’s

interest,” The American Conservative, March 24, 2003, www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/whose-war/

[10] Stephen Sniegoski, The Transparent Cabal: The Neoconservative Agenda, War in the Middle East, and the National Interest of Israel, Enigma Edition, 2008, p. 156.

[12] Stephen Sniegoski, The Transparent Cabal, op. cit., p. 120.

[13] April 11, 2002, quoted in Justin Raimondo, The Terror Enigma: 9/11 and the Israeli Connection, iUniverse, 2003, p. 19.

[14] April 26, 2013, on MSNBC, watch on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZRlatDWqh0o.

[15] Noted by Inter-Press Service on March 29, 2004, under the title “U.S.: Iraq war is to protect Israel, says 9/11 panel chief,” and repeated by United Press International the next day, on www.upi.com.

[16] Norman Podhoretz, Breaking Ranks: A Political Memoir, Harper & Row , 1979, p. 335.

[17] Translated from the French edition, Yirmiyahu Yovel, L’Aventure marrane. Judaïsme et modernité, Seuil, 2011, pp. 119-120, 149–151.

[18] Yirmiyahu Yovel, L’Aventure marrane, op. cit., pp. 96–98, 141–143; Nathan Wachtel, Entre Moïse et Jésus. Études marranes (XVe-XIXe siècle), CNRS éditions, 2013, pp. 54–65.

[19] Yirmiyahu Yovel, L’Aventure marrane, op. cit., pp. 483, 347.

[20] Yirmiyahu Yovel, L’Aventure marrane, op. cit., pp. 149–151.

[21] Elliott Horowitz, Reckless Rites: Purim and the Legacy of Jewish Violence, Princeton University Press, 2006.

[22] Hannah Arendt calls him a “race fanatic” in The Origins of Totalitarianism, vol. 1: Antisemitism, Meridian Books, 1958, pp. 309–310.

[23] Stanley Weintraub, Disraeli: A Biography, Hamish Hamilton, 1993, p. 579.

[24] Kevin MacDonald, Separation and Its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism, Praeger, 1998, kindle 2013, k. 5876–82.

[25] Gilad Atzmon, The Wandering Who? A Study of Jewish Identity Politics, Zero Books, 2011, pp. 55–56.

[26] Moses Hess, Rome and Jerusalem: A Study in Jewish Nationalism, 1918 (on archive.org), pp. 71, 27.

[27] Moses Hess, Rome and Jerusalem, op. cit., p. 74.

[28] Quoted in Alfred Lilienthal, What Price Israel? (1953), 50th Anniversary Edition, Infinity Publishing, 2003, p. 14.

[29] Kaufmann Kohler, Jewish Theology, Systematically and Historically Considered, Macmillan, 1918 (on www.gutenberg.org), pp. 290, 378–380.

[30] Quoted in Kevin MacDonald, Separation and Its Discontents, op. cit., k. 5463–68.

[31] Daniel Gordis, Does the World Need Jews? Rethinking Chosenness and American Jewish Identity, Scribner, 1997, p. 177.

[32] Daniel Lindenberg, Figures d’Israël. L’identité juive entre marranisme et sionisme (1649–1998), Fayard, 2014, p. 10.

[33] Alison Weir, Against Our Better Judgment: The Hidden History of How the U.S. Was Used to Create Israel, 2014, k. 3280–94.

[34] Norman Finkelstein, The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering, Verso, 2014, p. 6.

[35] Benjamin Ginsberg, Jews in American Politics: Essays, dir. Sandy Maisel, Rowman & Littlefield, 2004, p. 22.

[36] Arthur Hertzberg, The Zionist State, Jewish Publication Society, 1997, p. 94.

[37] David Ben-Gurion and Amram Duchovny, David Ben-Gurion, In His Own Words, Fleet Press Corp., 1969, p. 116

[38] Official website: www.jerusalemsummit.org/eng/declaration.php.

[39] Dan Kurzman, Ben-Gurion, Prophet of Fire, Touchstone, 1983, pp. 17–18, 22, 26–28.

[40] Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld Publications, 2007, p. 144.

[41] Gilad Atzmon, Being in Time: A Post-Political Manifesto, Skyscraper, 2017, pp. 66-67.

[42] Avigail Abarbanel, “Why I left the Cult,” October 8, 2016, on mondoweiss.net

[43] Kim Chernin, “The Seven Pillars of Jewish Denial.” Tikkun, Sept./Oct. 2002, quoted in MacDonald, Cultural Insurrections, op. cit., pp. 27-28.

[45] Norman Podhoretz, World War IV: The Long Struggle Against Islamofascism, Vintage Books, 2008.

[46] Wesley Clark, Winning Modern Wars, Public Affairs, 2003, p. 130.

[47] Gilad Atzmon, Being in Time: A Post-Political Manifesto, Skyscraper, 2017, p. 187-209.

[48] Another example: Bernard Benyamin, Le Code d’Esther. Si tout était écrit…, First Editions, 2012.

[49] Benedict de Spinoza, Theological-political treatise, chapter 8, §11, Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 126-128.

[50] Arnold Toynbee, A Study of History, volume XII, Reconsiderations, Oxford University Press, 1961, p. 486, quoted on http://mailstar.net/toynbee.html

[51] Thomas Romer, The Invention of God, Harvard University Press, 2016.

[52] Read for example Israel Finkelstein and Neil Adher Silberman, David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible’s Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition, S&S International, 2007.

[53] All Bible quotes are from the Catholic New Jerusalem Bible, which

has the advantage of not altering YHWH into “the Lord,” as most other

English translations have done for unscholarly reasons.

[54] Israel Shahak, Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight of Three Thousand Years, Pluto Press, 1994, p. 10 .

[55] Philip Davies, In Search of “Ancient Israel”: A Study in Biblical Origins, Journal of the Study of the Old Testament, 1992, p. 94.

[56] Maurice Samuel, You Gentiles, New York, 1924 (on archive.org), pp. 74–75.

No comments:

Post a Comment