| |||

| |||

There is no risk/benefit data supporting use of HepB in newborns. This was written by a virologist friend of mine. |

ACIP Exposed: How Newborn Vaccination Policy Was Built on Assumptions, Not Evidence

The Hepatitis B Vaccine Birth-Dose Debate: Revealing the weak scientific footing behind an influential recommendation.

Last week, ACIP convened to review—and ultimately vote on—the national recommendation for giving newborns the Hepatitis B vaccine at birth

The full meeting can be viewed here:

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Please consider supporting my work.

The universal birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine was implemented in 1991. The first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine is typically given to newborns shortly after birth, often within 24 hours.

Burden of Disease Data was Presented by the CDC

*All data was provided by the CDC National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS) and presented by Dr. Cynthia Nevison, a contract employee with CDC.

📉Morbidity Trends

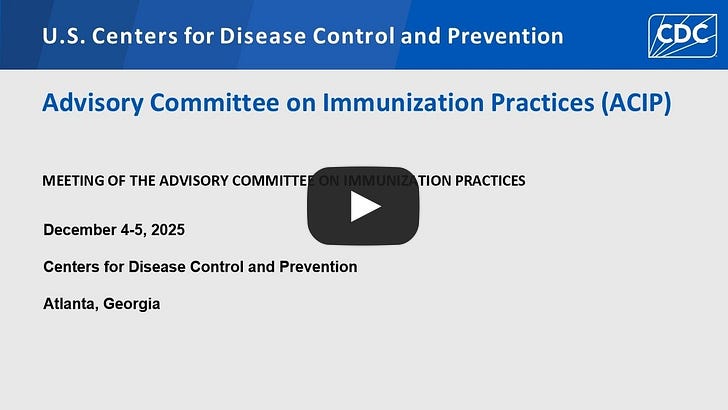

The US is the only low prevalence country that vaccinates all infants for hepatitis B. The prevalence for HBV in the United States has been estimated to be approximately 0.4%. Several countries without a birth dose show similar or even lower incidence rates than the United States.

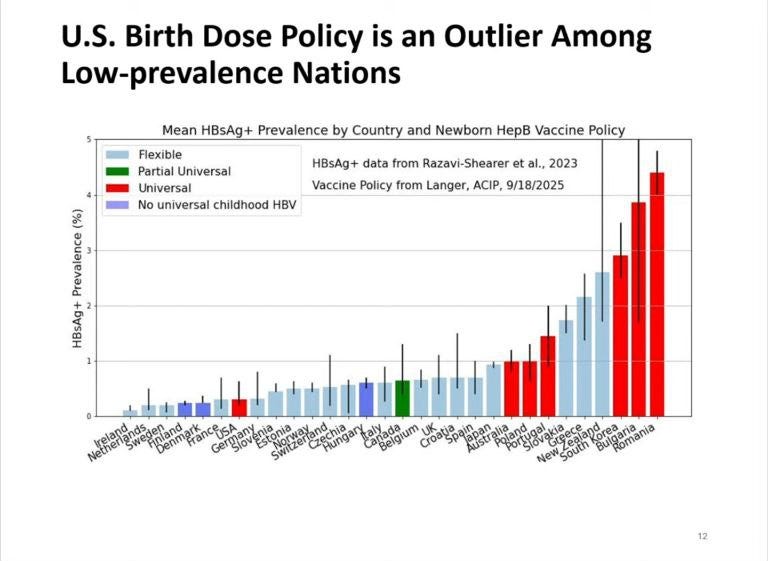

Cases of hepatitis B started to decline (beginning in 1985) well before the birth dose was implemented—down 33% by 1991 using targeted vaccination of at risk populations. The birth dose of the vaccine played no role in this decline. In fact, the incidence of acute hepatitis B in the United States declined as much as 80% between 1987 and 2004.

NOTE: The MMWR policy document from 1991, as quoted on the slide, was erroneous according to this graph.

The sharpest and most substantial decline in hepatitis B incidence occurred between 1990 and 2007 among adults aged 20 to 49, not among infants.

The greatest decline in hepatitis B cases was among those in the 20 and 30 year age groups (blue bars) with the greatest proportional decline occurring among the age group 15–24 years (87% decline). These are the age groups that are most active and engaged in the riskiest behaviors known to cause contraction of hepatitis B virus infection.

Source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3290915/

Several public health practices were cited for this decline including; increased screening of blood for hepB surface antigen (HBsAg), cleaner practices in dialysis, adoption of safer sex practices, needle exchanges, and screening and case management for HBsAG+ mothers.

🦠Chronic Cases

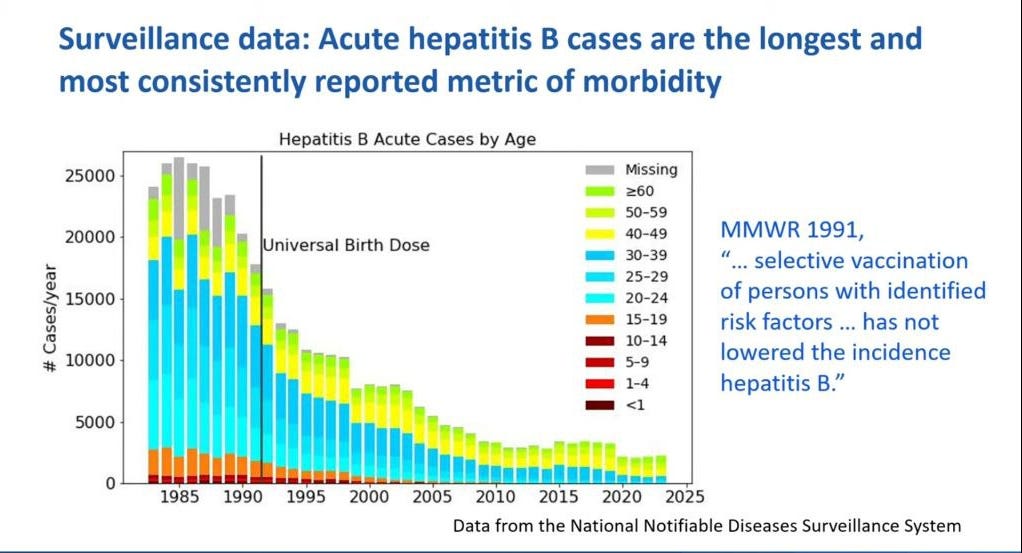

Collection of data on chronic cases of hepB in the US started only as recently as 2003. There was an uptick of cases but in older adults, those over 60 years of age while they observed an uptick of cases starting at age 30 beginning in 2020.

The universal birth dose is doing nothing to help older adults currently experiencing disease and need help.

🤰Perinatal (mother-to-child) Infections

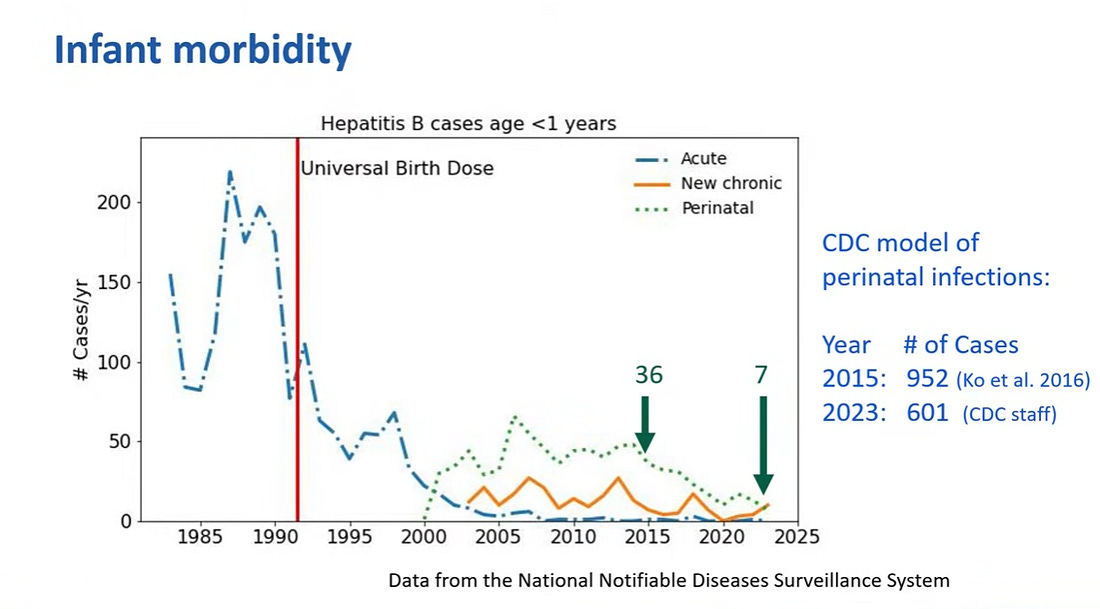

There was already a steep decline prior to the universal birth dose in acute cases of hepatitis B among infants most likely reflecting targeted vaccination of at risk infants.

Perinatal cases were down to 36 in 2015 and 7 in 2023 even though CDC modelling studies predicted many more cases.

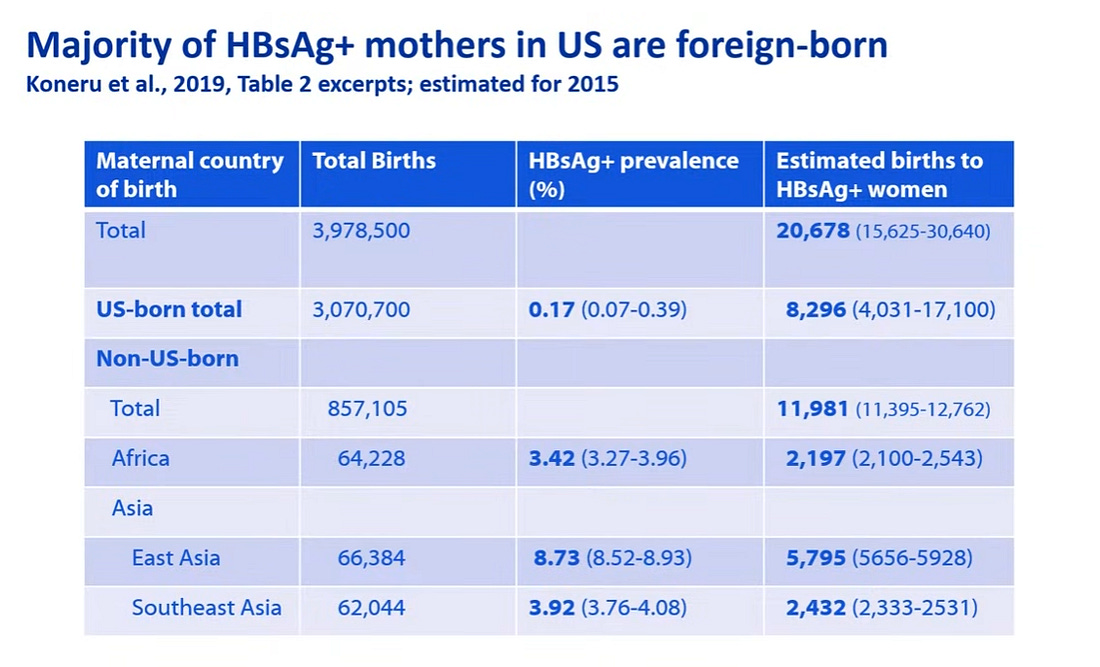

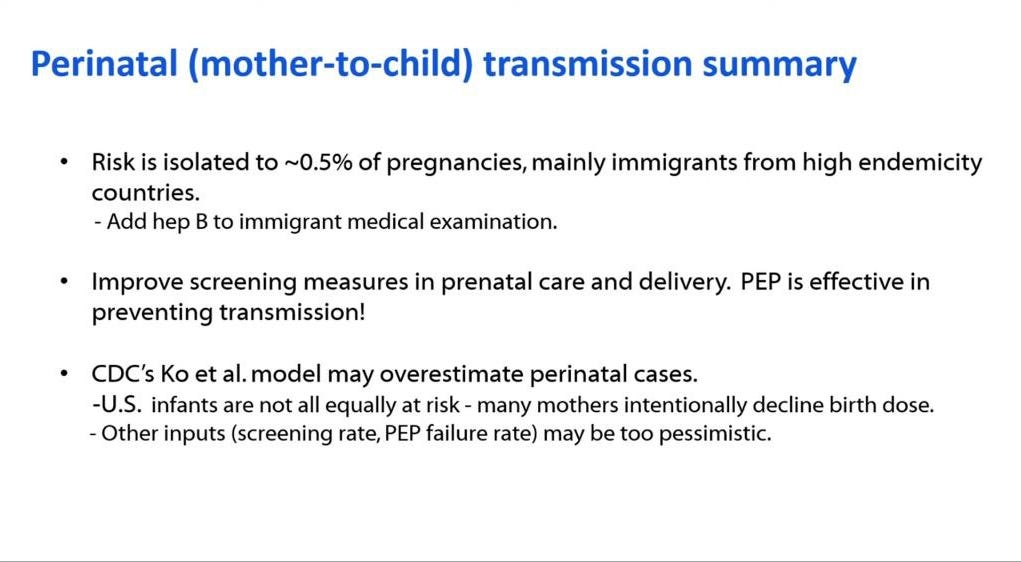

One study published in 2019 estimated the number of births to HBsAg+ women in the US. It showed that an estimated 20, 678 infants were born to HBsAg+ women in the US, representing 0.5% of all births (approx. 4 Mil births total).

Of about 21,000 positive women more than half were non US born immigrants with a majority from Southeast Asia and Africa.

In addition, according to the model 88% of women are screened during pregnancy based on CDC data so 98.5% of infants get post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) at birth. Of the 12% not screened, approximately 80% of infants still receive PEP at birth.

🧫Horizontal Transmission

What evidence exists for horizontal transmission and has the risk to American children been overstated?

In horizontal transmission, viruses are transmitted among individuals of the same generation that are not in a parent-child relationship.

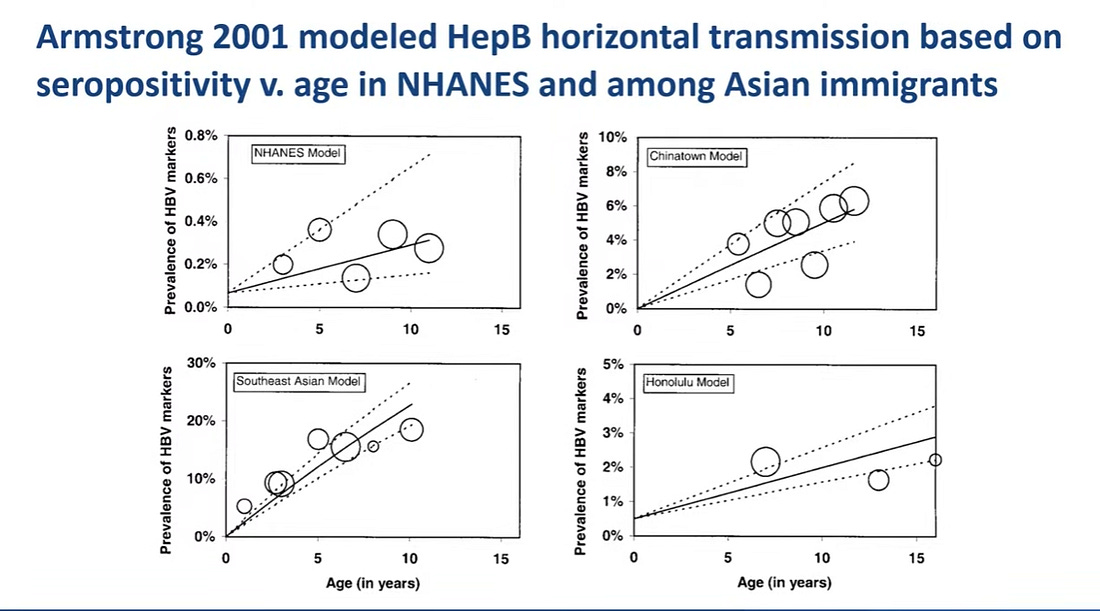

There was only one study assessing horizontal transmission and it was a modelling study. This study overestimated the number of cases. There is currently no evidence of horizontal transmission of hepatitis B in the total US population.

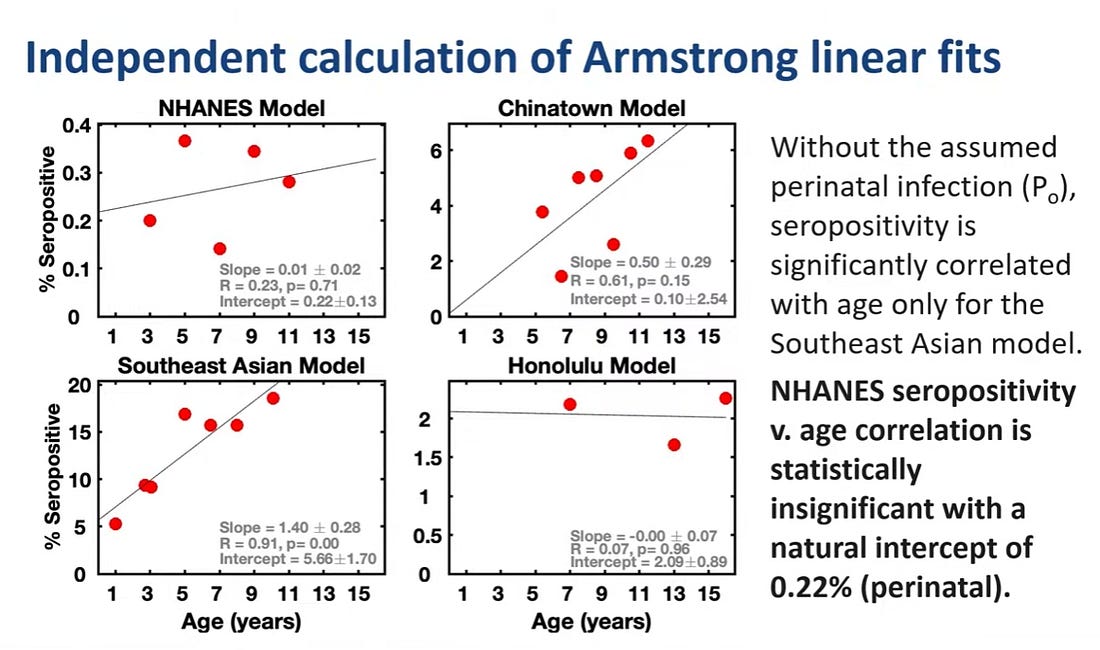

The NHANES model represents a typical American child and the fit is nearly a flat line meaning no risk of horizontal transmission. Horizontal transmission was only seen in one model, the Southeast Asia model which was conducted in communities with high rates of immigrants.

There is very little evidence that horizontal transmission has ever been a significant threat and the risk has been overstated, although it can occur among high-risk immigrant families.

🛡️Immunity from Hepatitis B vaccine

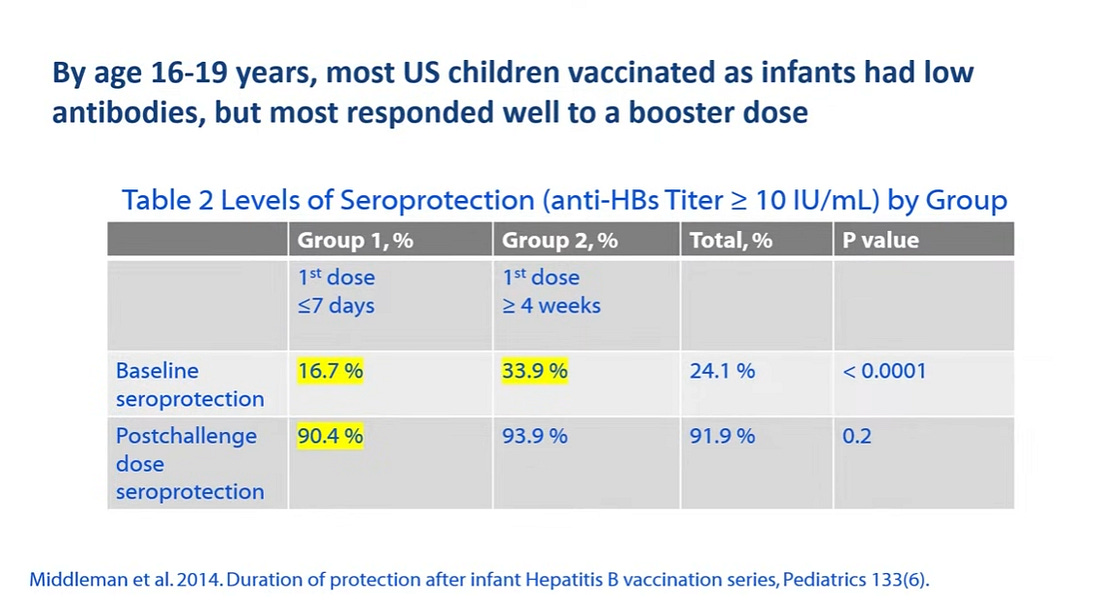

Antibody titers begin to wane depending on when the primary series of hepatitis B vaccination was initiated. The earlier the primary series is initiated the sooner antibodies begin to wane.

For those that received the primary series initiated between 5 and 19 years of age, 30 years later approximately 60% still had antibody titers while those vaccinated at less than 5 years old only 30% still had antibody titers.

Antibody titers waned most rapidly in children who begin the primary series as infants, especially when vaccinated as newborns. Of children in the US vaccinated as infants, less than 17% had antibody titers at 16-19 years of age.

⚠️“Safety” Data

Four areas were studied to assess “safety”: clinical trials, post-licensure safety studies, animal models and IOM and Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) on vaccine-related injuries

EVIDENCE IS LIMITED AND VARIES ACROSS SOURCES

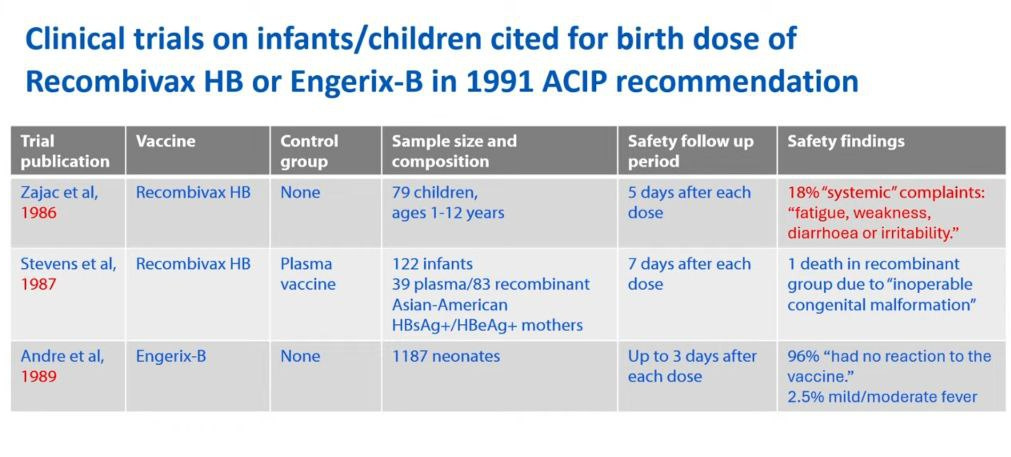

Clinical trials—there were no randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials in infants.

There were 3 studies in the 1980’s that were used for the birth dose vaccination but they had a low number of participants and short follow-up periods of 7 days or less with no ability to assess late onset or chronic conditions.

The systemic effects that were reported were fatigue/weakness, diarrhea, and irritability but those were dismissed as the baby just being fussy. However, these can be compared to and are similar to symptoms of encephalitis in infants.

Signs of encephalitis in babies include fever, extreme irritability or lethargy, poor feeding, vomiting, a bulging soft spot (fontanel), body stiffness, increased sensitivity to light/sound, and seizures, often preceded by viral symptoms like a cold.

Post-licensure “safety” studies

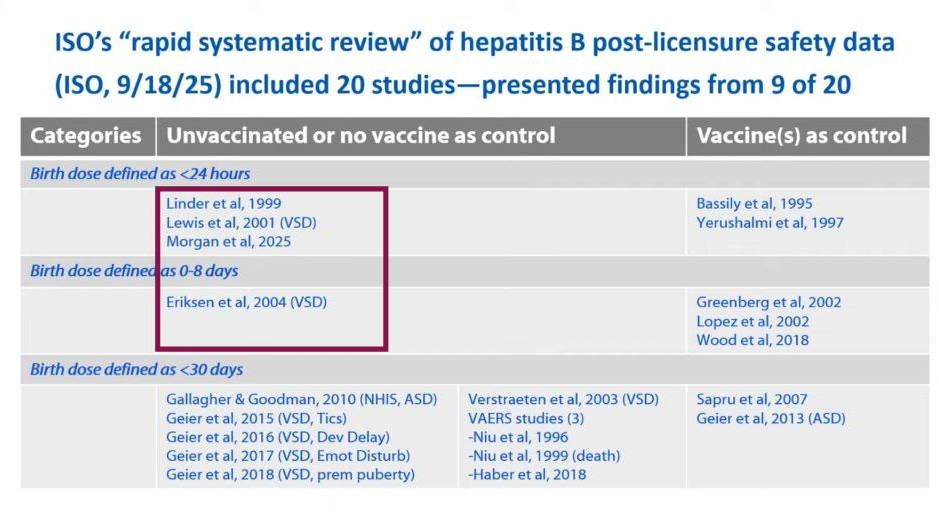

Twenty publications were found during a rapid systematic review of published literature for post-licensure safety data for the hepatitis B vaccine birth dose with 9 studies restricted to dose on day of birth (within 24 hours). Only 4 studies were reviewed in the presentation (see red box).

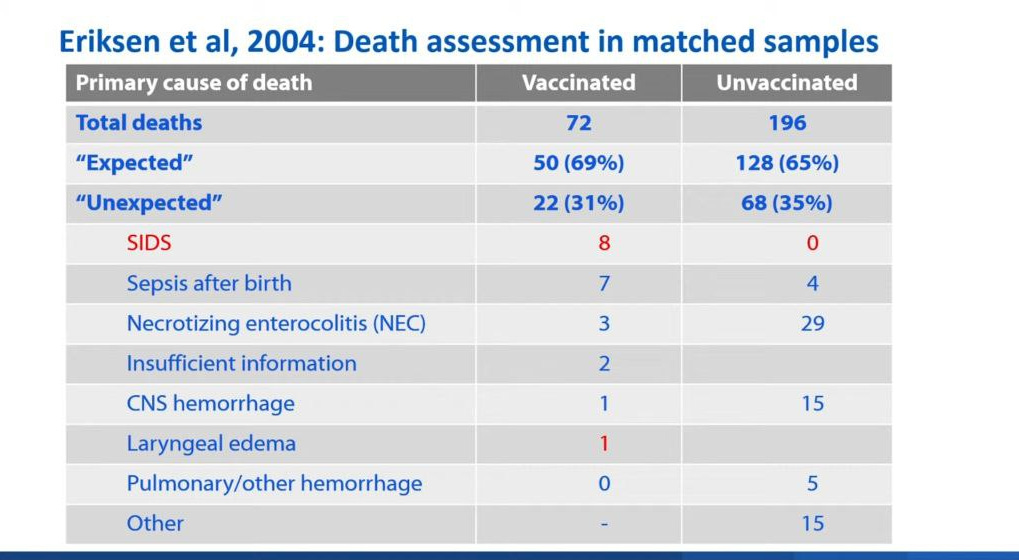

In the Eriksen et. al. study, there was a lower death rate in the unvaccinated group. There were more deaths due to SIDS in the vaccine group as compared to the unvaccinated group. In this study, the infants that were unvaccinated was generally because they were unhealthy or low birth weight.

IOM and VICP on vaccine-related injuries

VICP has processed a large number of hepatitis B vaccine claims and compensated many. They have paid out $92 million total for adult compensation claims and $18 million for infant payouts for hepatitis B vaccine alone with another $80 million in payouts due to hepatitis B in combination with other vaccines.

Animal models—show mechanism of injury, especially immune activation has been reported as well as neurobehavioral impairment.

CONCLUSION:

One major point that often gets overlooked in public conversations about infant vaccination is that a newborn’s immune system simply isn’t fully mature at birth. This early stage of immune development is essential to understand when we talk about how—and how well—vaccines can protect the youngest babies. Newborns do have an active immune system, but it’s still developing and functions very differently from the immune response of older children and adults.

A newborn’s immune system has its own strengths, limitations, and developmental timeline. Many components (like certain white blood cells and inflammatory responses) are less robust than in older children. Newborns do have innate immunity—the rapid, frontline system that jumps into action against unfamiliar threats. But many of its components operate at reduced strength compared to adults. Their white blood cells respond more slowly, inflammatory signaling is muted, and the system as a whole is still learning how to coordinate an effective defense.

The adaptive immune system, which creates targeted antibodies and long-term memory, is present but immature. Newborns can generate immune responses, but these responses are often weaker and don’t create durable memory as reliably as they do a few months later. This maturation process continues steadily through the first year of life.

Between birth and roughly 2–3 months of age, both the innate and adaptive immune systems begin to strengthen and coordinate more effectively. By about 3–4 months, infants can produce more robust antibody responses, and by 6 months many aspects of the immune system function far more independently. Full immune maturation continues throughout early childhood.

In addition, infants rely heavily on maternal antibodies—transferred during pregnancy and, for breastfed infants, through breast milk—to help protect them from infections in early life. During pregnancy, mothers transfer IgG antibodies through the placenta. These antibodies peak at birth and slowly decline over the first 4–6 months. Breastfeeding adds another layer of defense: IgA antibodies that protect the baby’s gut, respiratory tract, and mucosal surfaces. These maternal antibodies don’t teach the baby’s immune system to create its own long-term memory, but they do offer powerful short-term protection during a vulnerable window.

Maternal antibodies gradually decline over the first 6–12 months of life, while the infant’s own antibody production and broader immune competence continue to develop throughout infancy and early childhood. Maternal antibodies can sometimes reduce the response to certain vaccines, which is why many vaccines are scheduled for later infancy.

Bottom Line: True informed consent is impossible when critical safety data simply do not exist. For the hepatitis B birth dose, there are no robust studies evaluating potential adverse effects in the first day of life making it challenging for parents and clinicians to fully weigh risks and benefits for each individual infant.

| |||||

| |||||

Sharing science based information to help educate and inform people on various topics of public health interest to assist in the fight to bring integrity and honesty back to medicine, science and public health. |

No comments:

Post a Comment