How Big Pharma Hijacked Evidence-Based Medicine, Part IEvidence-based medicine is not evidence-based nor medicineEditor’s note: This essay is too long for most email systems so please click on the headline to read the full piece on the Substack site. The Substack app has an audio reader built in if you want to listen to an article instead of reading it. If you need access to any of the articles listed below that are behind a paywall, try Sci-hub, it’s free and works pretty well. This article is a heavy lift, but I believe it rewards a careful reading. Stay tuned for Part II in the next few days. I. Introduction Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) is a relatively recent phenomenon. The term itself was not coined until 1991. It began with the best of intentions — to give frontline doctors the tools from clinical epidemiology to make science-based decisions that would improve patient outcomes. But over the last three decades, EBM has been hijacked by the pharmaceutical industry to serve the interests of shareholders rather than patients. Today, EBM gives preference to epistemologies that favor corporate interests while instructing doctors to ignore other valid forms of knowledge and their own professional experience. This shift disempowers doctors and reduces patients to objects while concentrating power in the hands of pharmaceutical companies. EBM also leaves doctors ill-equipped to respond to the autism epidemic and unable to produce the sorts of paradigm-shifts that would be necessary to address this crisis. In this article I will:

II. History of Evidence-Based Medicine Medicine faces the same challenges as any other branch of knowledge — deciding what is “true” (or at least “less wrong”). Since its emergence in 1992, EBM has become the dominant paradigm in the philosophy of medicine in the United States and its impact is felt around the world (Upshur, 2003 and 2005; Reilly, 2004; Berwick, 2005; Ioannidis, 2016). Through the use of evidence hierarchies, EBM privileges some forms of evidence over others. Hanemaayer (2016) provides a helpful genealogy of EBM. Epidemiology — “the branch of medical science that deals with the incidence, distribution, and control of disease in a population” — has been a recognized field for hundreds of years. But clinical epidemiology, defined as “the application of epidemiological principles and methods to problems encountered in clinical medicine” first emerged in the 1960s (Fletcher, Fletcher, and Wagner, 1982). Feinstein (1967) is credited as the catalyst for the emergence and growth of this new discipline. Feinstein, in his book Clinical Judgment (1967) wrote, “Honest, dedicated clinicians today disagree on the treatment for almost every disease from the common cold to the metastatic cancer. Our experiments in treatment were acceptable by the standards of the community, but were not reproducible by the standards of science.” So Feinstein proposed a method for applying scientific criteria to clinical judgements in clinical situations. According to Hanemaayer (2016), around the same time, David Sackett was leading the first department of clinical epidemiology at McMaster University in Canada. Sackett was influenced by Feinstein and trained an entire generation of future doctors in clinical epidemiology. In the 1970s, Archibald Cochrane expanded the use of randomized controlled trials to a broader range of medical treatments. In 1980, the Rockefeller Foundation funded the International Clinical Epidemiology Network (INCLEN) which took the methods and philosophy of clinical epidemiology worldwide. The efforts of INCLEN would later receive the support of the U.S. Agency for International Development, the World Health Organization, and the International Development Research Centre. Various terms have been used to describe the methods of clinical epidemiology. Eddy (1990) used the term “evidence-based.” At about the same time the residency coordinator at McMaster University, Dr. Gordon Guyatt, was referring to this growing discipline as “scientific medicine” but apparently this term never caught on with the residents (Sur and Dahm, 2011). Eventually Guyatt settled on the term “evidence-based medicine” in an article in 1991 (Sur and Dahm, 2011). An Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group (EBMWG) was formed, comprised of 32 medical faculty members mostly from McMaster University but also from universities in the United States. In 1992, the EBMWG planted a flag for their particular approach to the philosophy of medicine with an article in JAMA titled, “Evidence-Based Medicine: A New Approach to Teaching the Practice of Medicine.” The article reads less like a traditional scientific journal article and more like a political manifesto. In the first paragraph they announced their intention to supplant the traditional practices of doctors with the methods and results from clinical epidemiology.

The article mostly consists of recommendations to consult the epidemiological literature following “certain rules of evidence” which are not defined before making any clinical decision (EBMWG, 1992). The authors also provide an evaluation form for “more rigorous evaluation of attending physicians” based on how consistently they “substantiate decisions” by consulting the medical literature (EBMWG, 1992). But the important point was not the steps per se, but who had ultimate decision-making authority within the medical profession. The EBMWG (1992) article was an announcement that henceforth, clinical epidemiology was at the top of the authority pyramid (what remains to be explained is why doctors fell in line). Over the next ten years the EBMWG published twenty-five articles on EBM in JAMA (Daly, 2005). Many have questioned the tone and approach of the early EBMWG vanguard (see: Upshur, 2005; Goldenberg, 2005; and Stegenga, 2011 and 2014). But the article, along with extensive organizing within the medical community, had the desired effect. EBMWG (1992) has since been cited over 6,900 times and EBM has become hegemonic throughout medicine — thoroughly reshaping the practices of doctors, clinics, medical schools, hospitals, and governments. In 1994, Sackett left McMaster University to start the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford University which quickly became a dominant force in the EBM movement (Hanemaayer, 2016). Sackett et al. (1997) systematized EBM to include the following five steps:

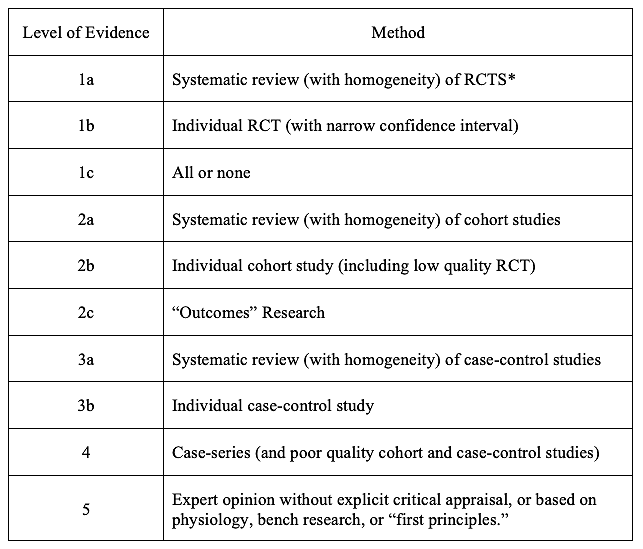

So far so good, but the Devil is always in the details. III. Evidence Hierarchies At first glance EBM appears straightforward and helpful. Problems appear once one tries to operationalize it. At the heart of evidence-based medicine are evidence hierarchies (Stegenga, 2014). Evidence hierarchies, as the name suggests, are categorical rankings that give preference to some ways of knowing over others. Rawlins (2008) found that 60 different evidence hierarchies had been developed as of 2006. Some of the best known evidence hierarchies include the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) (Stegenga, 2014). For the purposes of this initial discussion I will focus on the Oxford CEBM because it was the first in widespread use and it is representative of the larger field (Stegenga, 2014). Table 1, simplified version of Evidence Hierarchy, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine last updated by Howick, 2009: *The CEBM definition of “systematic reviews” sometimes includes meta-analysis. Source: Stegenga (2014). Available from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (2009). In theory, EBM and evidence hierarchies could be two separate things. In practice, evidence hierarchies are how one “critically appraises the evidence” — Step 3 in Sackett et al. 1997 described above (Stegenga, 2014). IV. Ten general and technical criticisms of evidence-based medicine and evidence hierarchies In this section I will review ten general and technical criticisms of EBM. The arguments are that: 1. EBM has become hegemonic in ways that crowd out other valid forms of knowledge; 2. Evidence hierarchies do not just sort data, they legitimate some forms of data and invalidate other forms of data; 3. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of RCTs are beset with epistemic problems; 4. Most RCTs are designed to identify benefits but they are not the proper tool for identifying harms; 5. RCTs are designed to address selection bias but other forms of bias remain; 6. Case reports and observational studies are often just as accurate as RCTs; 7. EBM is not based on evidence that it improves health outcomes; 8. EBM and evidence hierarchies reflect authoritarian tendencies in medicine; 9. Evidence hierarchies have reshaped the practice of medicine for the worse; and 10. Evidence hierarchies objectify and/or overlook patients. 1. EBM has become hegemonic in ways that crowd out other valid forms of knowledge. There is widespread agreement that EBM has become the dominant paradigm in clinical medicine. Upshur (2005) writes:

Reilly (2004) is unconcerned with EBM’s shortcomings and unequivocal in assessing its dominance in medicine today (this passage is flagged by critics of EBM including Goldenberg, 2009, and Stegenga, 2014 for its stridency):

Berwick (2005) provides a history of the promising early origins of EBM but then warns that things have gone too far. He writes:

Berwick (2005) then draws attention to common sense ways of knowing such as practice, experience, and curiosity, that are excluded by EBM (I love this quote!):

Far from setting doctors free to practice their craft at the highest level, Berwick (2005) sees EBM as encouraging doctors to exclude valuable ways of knowing:

2. Evidence hierarchies do not just sort data, they legitimate some forms of data and exclude other forms of data. Although EBM in the early years made reference to the totality of evidence, soon EBM became a way of excluding all studies except double-blind, randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) from the analysis. Stegenga (2014) writes: “The way that evidence hierarchies are usually applied is by simply ignoring evidence that is thought to be lower on the hierarchies and considering only evidence from RCTs (or meta-analyses of RCTs).” Often this is not just implicit but explicit:

Strauss et al. (2005), in a textbook on the practice and teaching of EBM, also suggests that some forms of evidence can be discarded:

3. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of RCTs are beset with epistemic problems. Meta analyses of RCTs and/or systematic reviews of RCTs are consistently at the top of most evidence hierarchies. The concept of aggregating the findings from several studies seems unassailable. But understanding how it works in practice reveals that it has the appearance of accuracy and objectivity only by eliding the subjectivity at the core of the technique. Meta-analyses tend to treat evidence as a commodity like wheat, copper, or sugar that just needs to be sorted and weighed. Stegenga (2011) explains that:

While meta-analysis aims for greater objectivity, in fact, it is still a subjective exercise. Stegenga (2011) writes, “Epidemiologists have recently noted that multiple meta-analyses on the same hypotheses, performed by different analysts, can reach contradictory conclusions.” Furthermore, many meta-analyses are plagued by the same financial conflicts of interest as RCTs and other ways of gathering evidence:

Meta-analyses are not nearly as precise as their proponents would have one believe.

Meta-analyses also suffer from low inter-rater reliability.

It is not that subjectivity itself is necessarily a problem. The subjective wisdom that comes from years of experience could be quite helpful in evaluating the evidence. The problem with meta-analyses as currently practiced is that those involved usually do not acknowledge their own subjectivity while simultaneously excluding the sort of reasoned subjective analysis (from doctors, patients, or perhaps even philosophers) that might be helpful. Indeed, meta-analyses as currently practiced leave out the political and economic contextual factors that are likely to corrupt a study’s results:

Stegenga (2011) concludes, “the epistemic prominence given to meta-analysis is unjustified.” 4. Most RCTs are designed to identify benefits but they are not the proper tool for identifying harms. Upshur (2005) writes that:

Michael Rawlins chaired the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (UK) from 1992 to 1998 and was the founding chair of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence from 1999 to 2013. From 2012 to 2014 he was President of the Royal Society of Medicine and in 2014 served as chair of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (roughly the equivalent of the medical portion of the U.S. Food & Drug Administration). Rawlins (2008) writes,

Rawlins (2008) concludes that “only observational studies can offer the evidence required for assessing less common, or long-latency, harms.” Stegenga (2014) writes,

Stegenga (2016) deepens his critique of how RCTs fail to detect harms:

Like Upshur (2005) and Rawlins (2008), Stegenga (2016) points out that most RCTs are just long enough to detect benefits but often not long enough to detect harms and the size of the trial is usually calculated to achieve statistical significance for obvious benefits while not being large enough to capture “severe but rare” harms. But he also points out ways that RCTs are intentionally manipulated to produce desired outcomes:

FDA post-market surveillance is under-funded by design and not sufficiently staffed to respond to the size of the task. Stegenga (2016) points out the ways that EBM contributes to make the problem worse:

Stegenga (2016) concludes that, “Because harms of medical interventions are systematically underestimated at all stages of clinical research, policy-makers and physicians generally cannot adequately assess the benefit-harm balance of medical interventions.” Systematically underestimating harms, lack of adequate information for regulatory decisions, and insufficient funding for post-market surveillance are a reflection of the power of pharmaceutical companies to shape the regulatory and political environment. 5. RCTs are designed to address selection bias but other biases remain. Upshur and Tracy (2004) write that the purpose of randomized trials is to minimize selection bias. However, they note, “this leaves undisturbed concerns about affluence bias, that is, the ability of certain interests to purchase and disseminate evidence; or the relevance bias, that is, the ability of interests to set the evidence agenda” (Upshur and Tracy, 2004). The high cost of RCTs means that there are only certain actors who are able to engage in this sort of research — usually pharmaceutical companies and academics working under large government grants. Rawlins (2008) points out that the median cost of an RCT in 2005-2006 in the U.K. was 3.2 million pounds (about 5.7 million U.S. dollars given exchange rates at the time) (p. 583). So privileging RCTs in evidence hierarchies privileges certain actors over others as well. The pharmaceutical companies who can afford to implement these methods have a strong incentive to find benefits and ignore harms from their products. Making matters worse, the evidence presented in this article suggests that RCTs are not epistemically superior to other levels in the evidence hierarchy nor are they necessarily superior to other ways of knowing not mentioned in the evidence hierarchies. EBM makes the same mistakes that Kuhn (1962) and other philosophers of science make — they overlook the very real problem of corporate influence. Gupta (2003) writes:

Jadad and Enkin (2007) argue that sources of bias are potentially limitless and they identify sixty of the most common types. So simply controlling for selection bias is not sufficient to guarantee scientific integrity. Furthermore, it is not even clear that RCTs as currently practiced actually prevent selection bias:

Perhaps the authors of these studies were simply careless in describing their methods. But given that directors of Contract Research Organizations boast of their ability to deliver the results desired by their clients (Petryna, 2007 in Mirowski, 2011) it seems reasonable to wonder whether double-blind randomization is actually happening at all in some clinical trials that purport to be RCTs. 6. Case reports and observational studies are often just as accurate as RCTs. The definition of a case report in the Dictionary of Epidemiology is notable for its internal contradiction:

So on the one hand, it is held that case reports are often refuted (even though no reference is supplied) and on the other hand, case reports “may also raise a thoughtful suspicion” (Porta, 2014). Case reports are second from the bottom in the CEBM evidence hierarchy, ranked above only “expert opinion” and below the threshold that many epidemiologists consider worth reading. “First reports” are case reports of the first recorded incidence of a new disease or adverse event in reaction to a new drug (or new use of an existing drug). But what is the actual evidence as to the reliability of such reports? Venning (1982) examined 52 first reports of suspected adverse drug reactions published in BMJ, the Lancet, JAMA, and NEJM in 1963. He followed up on each of these reports 18 years later to assess whether in fact they had subsequently been verified.

When one compares the 75% success rate of anecdotal first reports with the fact that 75-80% of the most widely cited cancer RCTs cannot be replicated (Prinz, Schlange, and Asadullah, 2011; Begley and Ellis, 2012), the decision to place RCTs at the top of the CEBM evidence hierarchy, while denigrating case series, appears unwarranted. Three studies from the early 2000s confirm that RCTs are not superior to observational studies.

In 2017, Thomas Frieden, the former Director of the CDC, made the case in the New England Journal of Medicine that a wide range of different study types can have a positive impact on patients and policy. He makes the simple point that each type of study has strengths and weaknesses and the study type should match the type of problem the researchers are trying to address. He points out that alternative data sources are “sometimes superior” to RCTs. So a wide range of different types of evidence can be valid and help inform clinical decision-making and yet the current practice of EBM systematically excludes everything other than the large RCTs favored by pharmaceutical companies. 7. EBM is not based on evidence that it improves health outcomes. Numerous authors, including Sackett and his colleagues, have acknowledged that EBM violates its own evidence-based norms because “there is no evidence that EBM is a more effective means of pursuing health than medicine-as-usual” (Norman 1999 in Gupta, 2003). Upshur (2003) notes that, “Ironically, the creation of these classifications has not as yet been informed by research but is driven in large part by expert opinion.” Defenders of EBM (such as Reilly, 2004) state that such evidence is not provided because it “cannot be proved empirically.” Yet that is not exactly true. One could easily create a natural experiment that compares patient outcomes between two equally ranked hospitals where one continues with business as usual and another implements EBM. While not exactly an RCT, there would be ways to compare before and after results within and between hospitals and even blind investigators. Upshur and Tracy (2004) write:

EBM began with the assumption that surely it would improve patient outcomes but there is little evidence to support that assumption.

It’s interesting to note that the rise in chronic illness in the United States (1986 to the present) roughly corresponds to the rise in EBM in the medical profession (1992 to the present). EBM has been completely unable to stop the rise in chronic illness (particularly among children) but the rise in the stock market value of pharmaceutical companies since 1992 has been spectacular. 8. EBM and evidence hierarchies reflect authoritarian tendencies in medicine. A number of authors have highlighted the authoritarian tendencies of EBM. Shahar (1997) was one of the earliest critics to note the authoritarian tendencies of the EBM movement:

Rosenfeld (2004) is fulsome in her praise for the early days of EBM:

But Rosenfeld (2004) then argues that those promising early days have receded to reveal a much more troubling current reality:

Rosenfeld (2004) is especially critical of the EBM gatekeepers that prepare meta-analyses for consumption by the wider medical community:

Rosenfeld (2004) concludes: “We have come full circle to faith-based medicine. We are encouraged and, even, forced to mould our practice of medicine to the authority of those practitioners of EBM that are ‘approved’ and ‘acceptable.’” Upshur (2005) similarly recounts the shift from the joyful early days of EBM to its more troubling present form:

9. Evidence hierarchies have reshaped the practice of medicine for the worse. Evidence hierarchies have reshaped the practice of medicine in ways that are advantageous to pharmaceutical companies and disadvantageous to doctors and patients. Upshur (2003), recounting a story from his medical practice, gives a glimpse of how pharmaceutical companies use EBM to sell their products:

The process that doctors are taught to use in connection with EBM is an idealized process. In the real world, doctors rarely have the time to follow all of the steps. So instead, they use shortcuts supplied by medical publishers and others.

This shift from evidence-based practitioner to evidence user is presented by proponents of EBM as an acceptable alternative to the idealized process. Yet if one examines these developments in their wider context, it is clear how problematic they are. What started out as a process to empower doctors now has doctors essentially taking orders from the pharmaceutical companies who run most of the clinical trials. Even though many of these studies are not replicable, harried doctors with detailers in their office showing them the latest “evidence-based medicine” are going to feel enormous pressure to conform. Clinicians who do not follow the latest EBM guidelines may also wonder whether such independent thinking might expose them to additional risk of malpractice suits. Groopman (2007) in How Doctors Think describes the impact of EBM on the hospital workplace and the mindset of doctors:

What likely started out with good intentions, can become paint-by-numbers medicine that constrains the wisdom and creativity of some of our finest minds:

Goldenberg (2009) provides an extraordinary account of the political economy of EBM and how EBM shapes the mode of production in medicine:

EBM is now a brand and everything that goes along with being a brand — a shortcut to decision making, very powerful at shaping decisions, essential to marketing and profit but not a very precise indicator of the quality of the contents. 10. Evidence hierarchies objectify and/or overlook patients. EBM objectifies patients in ways that run counter to the traditional practice of medicine and more recent paradigms such as “patient centered medicine.” Upshur and Tracy (2004), write, “[I]t is interesting to note that patients do not become relevant until Step 4 [in the EBM process outlined by Sackett et al., 1997, summarized above]. In fact, patients are seen as passive objects that have evidence applied to them after the information has been extracted from them.” Such discounting of patients’ experiences and inherent subjectivity would seem to be a violation of fundamental values in medicine and yet it is the dominant philosophy of medicine today. Upshur (2005) writes:

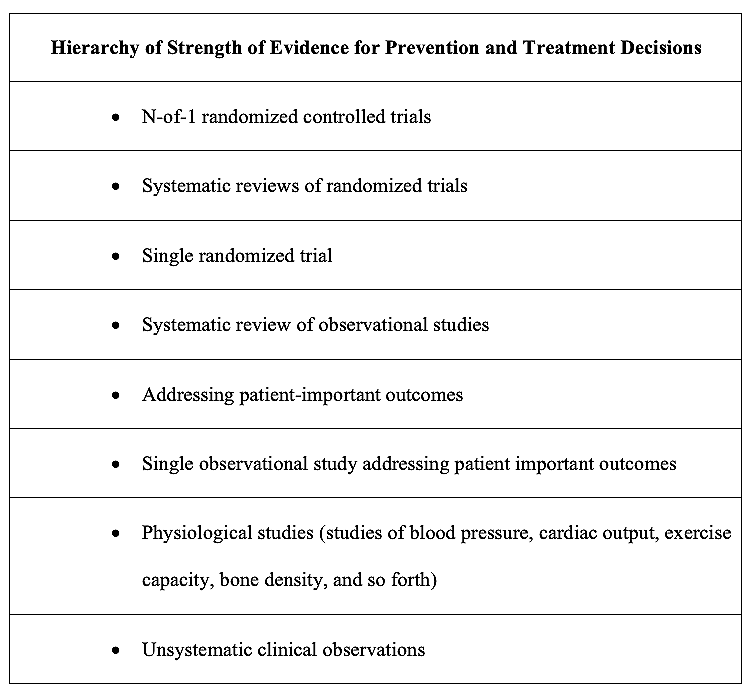

I will return to this issue below in my discussion of implications for the autism epidemic. V. The AMA’s 2002, 2008, and 2015 evidence hierarchies In 2002, the American Medical Association created its own evidence hierarchy, The Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature (Guyatt and Rennie 2002) and it contained a fascinating twist. It resembled the CEBM, except at the very top of the hierarchy, the AMA listed N-of-1 randomized control trials. Table 2 Source: Guyatt and Rennie (2002), p. 7. An N-of-1 trial is a clinical trial in which a single patient is the entire sample population. N-of-1 trials can be double-blinded (both patient and doctor do not know the treatment vs. the placebo) and the order of treatment and control can be randomized using various patterns (Guyatt, et al., 1986, p. 889-890). N-of-1 medicine is an important step in the right direction because it reflects a philosophy of medicine that is in keeping with the heterogeneity of the human population. But few formal N-of-1 trials are conducted each year. By 2008, Kravitz et al. wrote, “What ever happened to N-of-1 trials?” noting that “Despite early enthusiasm, by the turn of the twenty-first century, few academic centers were conducting n-of-1 trials on a regular basis” (p. 533). Lillie et al. (2011) write, “Despite their obvious appeal and wide use in educational settings, N-of-1 trials have been used sparingly in medical and general clinical settings” (p. 161). Curious about the dearth of N-of-1 trials, I started researching what happened. And what I discovered shocked me. In 2000, the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Work Group began to meet. Gordon Guyatt was one of its leaders. By 2004 they published their framework and it is the opposite of transparent — it takes the different levels from the evidence hierarchy and converts them into a “quality scale” — “high, moderate, low, and very low.” At the top of their evidence hierarchy is RCTs. So according to GRADE, if a study is an RCT, it is considered “high quality” which is defined as “We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate.” GRADE converted a system based on data to one based on normative labels — “high quality,” “high confidence,” even though as I have shown above, RCTs are not more reliable than other forms of evidence. GRADE is an opaque wrapper that hides what’s inside the model and gives all the power in decision-making to the people preparing the recommendations. Governments and public health agencies including the WHO, FDA, and CDC love GRADE because it tells people what to do in no uncertain terms without having to deal with the messiness of odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p values. In 2008, the American Medical Association published a new edition of The Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature and N-of-1 trials had been downgraded below systematic reviews of RCTs. Given how these evidence hierarchies work, anything below the first tier is considered inferior and ignored which means that the AMA had abandoned N-of-1 as a valid methodology for clinical decision-making. The third edition of The Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature published in 2015 fully embraces GRADE as the AMA’s preferred framework for making prevention and treatment decisions. I saw GRADE in use when I watched every meeting the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) and the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2022 and 2023. GRADE is a tool to give legitimacy to ANY medical intervention no matter how abysmal the data. For example, the FDA and CDC used GRADE to authorize:

So within 13 years (from the first edition in 2002 to the third edition in 2015) the AMA went from the best-in-class evidence hierarchy that acknowledged individual difference to a cartoonish monstrosity, GRADE, that is just a tool for laundering bad data on behalf of the pharmaceutical industry. In the process the AMA sold out the doctors in their association and the patients in their care to the drug makers. VI. More details on the corporate takeover of EBM Ioannidis (2016) recounts his conversations and correspondence with David Sackett over the course of many years about how EBM changed since its initial conception:

One of the many problems with EBM is that focusing on poorly defined notions of “quality” sometimes overlooks important dynamics and variables.

As I pointed out in chapter 5 of my doctoral thesis, even meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which sit at the top of most evidence hierarchies, are contaminated by corporate influence. Iaonnidis (2016) notes that even the widely respected Cochrane Collaboration “may cause harm by giving credibility to biased studies of vested interests through otherwise respected systematic reviews” (p. 84). Ioannidis (2016) provides a vivid illustration of the current mode of production in medicine and how EBM has become the corporate tail wagging the dog.

This is a startling turn of events. Doctors are often seen as heroic, selfless, and wise. EBM was conceived with the best of intentions to further improve medical practice. And yet, Ioannidis (2016) is openly stating that the whole endeavor has been hijacked to serve corporate ends rather than patient needs. VII. Analysis and implications for the autism epidemic I want to highlight nine facets of EBM and evidence hierarchies as they apply to the autism epidemic. 1. CEBM, GRADE, and other evidence hierarchies replace the varied ways of knowing with a single tool — RCTs. Supporters of EBM seem to base their model entirely on an idealized view of science. A more “evidence-based” approach would be to read the CEBM evidence hierarchy in the context of how science is actually done. Most RCTs are done at overseas (usually Chinese) CROs (Mirowski, 2011). 50% (Horton, 2015) to 80% (Prinz, Schlange, and Asadullah, 2011; Begley and Ellis, 2012) of what is published is not replicable. To claim that RCTs are the “highest quality” evidence and that one should not bother to read anything else is clearly untenable, unscientific, and not in the interests of patients. 2. It is striking how much the CEBM evidence hierarchy, GRADE, and other evidence hierarchies degrade the contribution of doctors. Starr (1982, 1997) and others have pointed out that doctors have been gradually losing agency as capital and corporations have come to play an ever-greater role in medicine. But to place a doctor’s “expert opinion” at the bottom of the hierarchy, below even “poor quality cohort and case-control studies” is an example of epidemiologists putting their own work above those actually practicing and interfacing with patients in the real world. Instead of viewing doctors as trusted advisors whose instincts, experience, and intuition are key to successful outcomes, the CEBM, GRADE, and other evidence hierarchies regard doctors as the least reliable form of evidence. In the process, the role of the doctor shrinks from discernment to obedience. 3. Individual patients are nowhere to be found in the CEBM evidence hierarchy, GRADE, or other evidence hierarchies. One’s own perspective and insights into one’s disease state do not even make it onto the chart at all. The experiences and insights of patients, the views of doctors, and alternative forms of evidence can provide the data that challenge paradigms. To denigrate these ways of knowing leaves existing paradigms in place even when they have failed to serve the public. 4. EBM has changed the practice of medicine. “In 2023, the United States had 1,010,892 active physicians of which 851,282 were direct patient care physicians” (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2024). There are multiple ways of knowing including RCTs, meta-analyses and systematic reviews, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, ecological studies, observational studies, case reports and series, registries, bench research, and more. In a crisis like autism, it would seem that all available resources — the talents of over a million trained professionals and multiple ways of knowing would be brought to bear on stopping the epidemic. By contrast, EBM represents a deskilling and circumscribing of the practice of doctors, an exclusion of multiple streams of evidence, and a turning over of the process of discovery to a smaller number of specialists, often in the employ of pharmaceutical companies. The result is a calcified practice of medicine, ill-equipped to respond to the crises it faces and the crises to which it contributes. 5. From the corporate-funded studies that produce the outcomes desired by their patrons, to the studies that never get funded, to the studies that get funded only to get quashed, to the studies that get completed but that never lead to regulation, to the rules of “scientific” evidence in the courts that protect corporations and harm plaintiffs, to the philosophy of medicine that discounts methods for detecting harms and favors corporate ways of knowing over other valid epistemologies — medicine in the U.S. is a system that is more hegemonic than scientific; more an expression of power relations than a method for producing good data or improved health outcomes for patients. It is a system that is quite good at protecting the profitable status quo but not very good at producing the sort of open-ended inquiry that can lead to the paradigm shifts necessary to stop the autism epidemic. 6. Given a philosophy of medicine that privileges a certain sort of epidemiology to the exclusion of all other forms of knowing, is it any wonder then that doctors routinely dismiss the thousands of parents who try to explain to their doctors the origins of their child’s autism symptoms (Campbell, 2010; Habakus and Holland, 2011; Handley, 2018)? The experiences of these parents were dismissed long before the family ever walked in the door — they were excluded in medical school when the future doctor was studying evidence-based medicine and learning to follow an epistemology that favors corporate interests and excludes other ways of knowing. 7. It is beyond infuriating that evidence-based medicine has spent more than three decades extolling the virtues of double-blind, randomized, controlled trials, and yet all of the so-called RCTs in connection with vaccines are fraudulent. Everyone knows that they are fraudulent (even though the mainstream medical profession tries to excuse this fraud). In clinical trials for vaccines, the control group is not given an inert saline placebo and is given another toxic vaccine or the toxic adjuvants from the trial vaccine instead. The Informed Consent Action Network (2023) has the receipts. So at the end of the day, the entire evidence-based medical system — including the tens of thousands of published papers and the thousands of careers dedicated to promoting EBM — is a giant theatrical production to empower epidemiologists and enrich the pharmaceutical industry. The professionals involved do not believe their own stated values and are actively participating in the mass poisoning of the population and the destruction of civilization. This is one of the most extreme examples of a failure of moral courage and dereliction of scientific duty in the history of the world. 8. If one wants to be scientific, it would follow that one should turn to those who are making important discoveries first. The parents’ group, the National Society for Autistic Children (founded by Bernard Rimland, now the Autism Society of America) proposed an environmental influence on autism in 1974 (Olmsted and Blaxill, 2010), forty-two years before Project TENDR reached the same conclusion (Bennett et al., 2016). By the mid 1990s, it was common knowledge among parents of children with autism, that autism had a gastrointestinal component (Kirby, 2005) — two decades before the microbiome became the “new frontier in autism research” (Mulle, Sharp, and Cubells, 2013). We know that EBM is a fraud because it ranks rigged corporate studies ahead of the paradigm-shifting breakthroughs discovered by parents that are actually helping autistic children. 9. Going forward, any system of medicine in connection with autism must start with the individual child and his/her family as the highest form of evidence (because obviously they are). All forms of data, no matter how unconventional or “outside the box,” must be brought to bear on supporting recovery and preventing this injury from happening to others. Rigged corporate RCTs have no place in actual medicine; their only appropriate use is as evidence of crimes against humanity in future Nuremberg trials of pharmaceutical executives and their enablers in government. The revolution we seek is thus a return to actual science instead of the genocidal corporate nonsense posing as evidence-based medicine today. REFERENCES Association of American Medical Colleges (2024). “U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard.” https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2024-key-findings-and-definitions Begley, C. G., & Ellis, L. M. (2012, March 28). Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature, 483(7391), 531–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/483531a Bennett D, et al. (2016). Project TENDR: Targeting Environmental Neuro-Developmental Risks. The TENDR Consensus Statement. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124, A118-A122. http://doi.org/10.1289/EHP358 Benson, K. & Hartz, A. J. (2000, June). A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. NEJM;342(25):1878–1886. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200006223422506 Berwick, D. M. (2005). Broadening the view of evidence-based medicine. Quality and Safety Health Care, 14, 315-316. http://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.015669 Borgerson, K. (2009). Valuing Evidence: Bias and the Evidence Hierarchy of Evidence-Based Medicine. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 52(2), 218-233. http://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0086 Campbell, J. (2010). Parents Voice: Children’s Adverse Outcomes Following Vaccination. http://www.followingvaccinations.com/ Concato, J., Shah, N., & Horwitz, R. I. (2000, June 22). Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. NEJM;342(25):1887–1892. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200006223422507 Daly, J. (2005). Evidence-Based Medicine and the Search for a Science of Clinical Care. Berkeley: University of California Press. Eddy, D. M. (1990). Practice Policies: Guidelines for Methods. JAMA, 263(13), 1839-1841. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1990.03440130133041 epidemiology. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster.com. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/epidemiology Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, (1992, November 4). Evidence-Based Medicine: A New Approach to Teaching the Practice of Medicine. JAMA, 268(17), 2420-2425. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032 Feinstein, A. R. (1967). Clinical Judgment: The Theory and Practice of Medical Decision. New York, NY. Fletcher, R. H., Fletcher, S. W., & Wagner, E. H. (1982). Clinical epidemiology: The essentials. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. Frieden, T. R. (2017, August 3). Evidence for Health Decision Making — Beyond Randomized, Controlled Trials. NEJM; 377:465-475. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1614394 Gadamer, Hans-Georg. (1975). Truth and Method. New York: Seabury Press. Goldenberg, M. J. (2009, Spring). Iconoclast or Creed?: Objectivism, Pragmatism, and the Hierarchy of Evidence. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 52(2). http://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0080 Groopman, J. (2007). How Doctors Think. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Gupta, M. (2003). A critical appraisal of evidence-based medicine: Some ethical considerations. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 9(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00382.x Guyatt, G., Sackett, D., Taylor, D. W., Ghong, J., Roberts, R., & Pugsley, S. (1986). Determining optimal therapy—randomized trials in individual patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 314(14), 889-892. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM198604033141406 Guyatt, G. H., & Rennie, D. (Eds.). (2002). Users’ guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice. American Medical Association. Guyatt, G. H., Rennie, D., Meade, M. O., & Cook, D. J. (Eds.). (2008). Users’ guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. Guyatt, G. H., Rennie, D., Meade, M. O., & Cook, D. J. (Eds.). (2015). Users’ guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. Habakus, L. K., and Holland, M. (Editors). (2011). Vaccine Epidemic. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. Handley, J. B. (2018). How to end the autism epidemic. Chelsea Green Publishing. Hanemaayer, A. J (2016, December). Evidence-Based Medicine: A Genealogy of the Dominant Science of Medical Education. Journal of Medical Humanities, 37(4), 449-473. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-016-9398-0 Haynes, R. 2002. What kind of evidence is it that evidence-based medicine advocates want health care providers and consumers to pay attention to? BMC Health Services Research 2:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-2-3 Hazell, L., & Shakir, S. A. W. (2006). Under Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions: A Systematic Review. Drug Safety, 29(5), 385–396. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00002018-200629050-00003 Horton, R. (2015). Offline: What is medicine’s 5 sigma? The Lancet, 385(9976), 1380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60696-1 Howick, J. H. (2011). The Philosophy of Evidence-based Medicine. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Informed Consent Action Network (2023, October 18). Childhood Vaccine Trials Summary Chart. https://icandecide.org/article/childhood-vaccine-trials-summary-chart/ Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2016). Evidence-based medicine has been hijacked: a report to David Sackett. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 73, 82-86. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.02.012 Jadad, A. R. and Enkin, M. W. (2007). Randomised Controlled Trials: Questions, Answers and Musings, 2nd Edition. Malden, Massachusetts: BMJ Books. Kesselheim, A. S., Mello, M. M., & Studdert, D. M. (2011). Strategies and practices in off-label marketing of pharmaceuticals: a retrospective analysis of whistleblower complaints. PLoS Med, 8(4), http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000431 Kirby, D. (2005). Evidence of Harm: Mercury In Vaccines and the Autism Epidemic: A Medical Controversy. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Kravitz, R. L., Duan, N., Niedzinski, E. J., Hay, M. C., Subramanian, S. K., & Weisner, T. S. (2008). What Ever Happened to N-of-1 Trials? Insiders’ Perspectives and a Look to the Future. The Milbank Quarterly, 86(4), 533–555. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00533.x Lillie, E. O., Patay, B., Diamant, J., Issell, B., Topol, E. J., & Schork, N. J. (2011). The n-of-1 clinical trial: the ultimate strategy for individualizing medicine? Personalized Medicine, 8(2), 161-173. http://doi.org/10.2217/pme.11.7 Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. (2014, 3 November). Professor Sir Michael Rawlins appointed Chair of Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Press release. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/professor-sir-michael-rawlins-appointed-chair-of-medicines-and-healthcare-products-regulatory-agency Mirowski, P. (2011). Science-Mart: Privatizing American Science. Harvard University Press. Mulle, J. G., Sharp, W. G., and Cubells, J. F. (2013). The Gut Microbiome: A New Frontier in Autism Research. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(2), 337. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0337-0 Olmsted, D. and Blaxill, M. (2010). The Age of Autism: Mercury, Medicine, and a Man-Made Epidemic. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Petticrew, M. & Roberts, H. (2003). Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: horses for courses. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2003 Jul;57(7):527–529. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.7.527 Porta, M. (2014). Dictionary of Epidemiology, 6th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Prinz, F., Schlange, T., & Asadullah, K. (2011). Believe it or not: how much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 10, 712. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3439-c1 Rawlins, M. (2008, December). De Testimonio: on the evidence for decisions about the use of therapeutic interventions. Clinical Medicine, 8(6). http://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.8-6-579 Reilly, B. M. (2004). The essence of EBM. BMJ, 329(7473), 991-992. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC524538 Rosenfeld, J. A. (2004), The view of evidence-based medicine from the trenches: liberating or authoritarian? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 10, 153-155. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00472.x Sackett, D. L., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W. M. C., and Haynes, R. B. (1997). Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. London: Churchill Livingstone. Shahar, E. (1997). A Popperian perspective of the term ‘evidence-based medicine’. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 3, 109-116. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.1997.00092.x Starr, P. (1982, 1997). The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books. Stegenga, J. (2011). Is Meta-Analysis the Platinum Standard of Evidence? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 42, 497-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.07.003 Stegenga, J. (2014, October). Down the with Hierarchies. Topoi, 33(2), 313-322. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-013-9189-4 Stegenga, J. (2015). Herding QATs: Quality Assessment Tools for Evidence in Medicine. In. Huneman, P. et al. (eds.), Classification, Disease, and Evidence, History Philosophy and Theory of the Life Sciences 7. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8887-8 Stegenga, J. (2016). Hollow Hunt for Harms. Perspectives on Science, 24(5), 481-504. http://doi.org/10.1162/POSC_a_00220 Straus, S. E., Glasziou, P., Richardson, W. S. and Haynes, R. B. (2005). Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach It. London: Churchill Livingstone. Sur, R. L., & Dahm, P. (2011). History of evidence-based medicine. Indian Journal of Urology : IJU : Journal of the Urological Society of India, 27(4), 487-489. http://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.91438 Upshur, R. E. G. (2003, September 30). Are all evidence-based practices alike? Problems in the ranking of evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 169(70), 672-673. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC202284/ Upshur, R. E. G. (2005, Autumn). Looking for rules in a world of exceptions: reflections on evidence-based practice. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 48(4), 477-489. http://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2005.0098 Upshur, R. E. G. and Tracy, C. S. (2004, Fall). Legitimacy, Authority, and Hierarchy: Critical Challenges for Evidence-Based Medicine. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4(3), 197-204. http://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh018 Venning, G. R. (1982, 23 January). Validity of anecdotal reports of suspect adverse drug reactions: the problem of false alarms. BMJ, 284(6311), 249-252. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1495801/ Blessings to the warriors. 🙌 Prayers for everyone fighting to stop the iatrogenocide. 🙏 Huzzah for everyone building the parallel society our hearts know is possible. ✊ In the comments, please let me know what’s on your mind. As always, I welcome any corrections. You're currently a free subscriber to uTobian. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

No comments:

Post a Comment