The Gut: Where Bacteria and Immune System Meet

November 2015—By now, it’s a familiar fact: Humans have more bacterial cells—a lot more—than human cells. Bacteria live on the skin, in the nose and ears, and, most of all, in the gut.

Until recently, if most people thought about those bacteria at all, we tended to think of them as fairly separate from us. They help with digestion, but otherwise they stay on their side of the intestinal lining, and we stay on our side. But, in fact, there is a lot of interaction between the body’s immune system and bacteria in the gut. Researchers at Johns Hopkins are now in the early stages of figuring

out how the composition of the gut changes in different diseases, how the body’s immune system interacts with these tiny hitchhikers and particularly how that relationship may function in disease.

“A huge proportion of your immune system is actually in your GI tract,” says Dan Peterson, assistant professor of pathology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “The immune system is inside your body, and the bacteria are outside your body.” And yet they interact. For example, certain cells in the lining of the gut spend their lives excreting massive quantities of antibodies into the gut. “That’s what we’re trying to understand—what are the types of antibodies being made, and how is the body trying to control the interaction between ourselves and bacteria on the outside?”

Bacteria and Cancer in the Gut

Cynthia Sears, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins and member of its Kimmel Cancer Center, studies the role of the microbiome in causing colon cancer in mice and humans. Colon cancer seems to stem from an interaction among the microbiome, the immune system and epithelial cells that line the colon.

The surface of colon tumors with (right) and without (left) layers of bacteria growing on top.

The surface of colon tumors with (right) and without (left) layers of bacteria growing on top.One of the actions set off by ETBF in the colon is called TH17 inflammation. This is largely thought to be useful for fighting off bacteria and fungi, but it can also turn against the body and cause cancer in the colon. Using mice, Sears’ group is trying to understand exactly what the TH17 response does to cells in the colon to promote cancer development.

No one species has been found to always cause colon cancer in humans. Instead, carcinogenesis may have to do with a shift in the ecology of the gut—that is, in the makeup of the bacterial community.

Scientists have suspected since the 1970s that bacteria contribute to colon cancer. But, as sequencing has gotten cheaper, it’s become much easier to ask questions about exactly what kind of role bacteria play in the disease. “Whether they’re the reason it starts or whether they contribute to the growth of tumors over time, I think, is a question that remains to be clearly answered,” Sears says.

From Lung to Belly

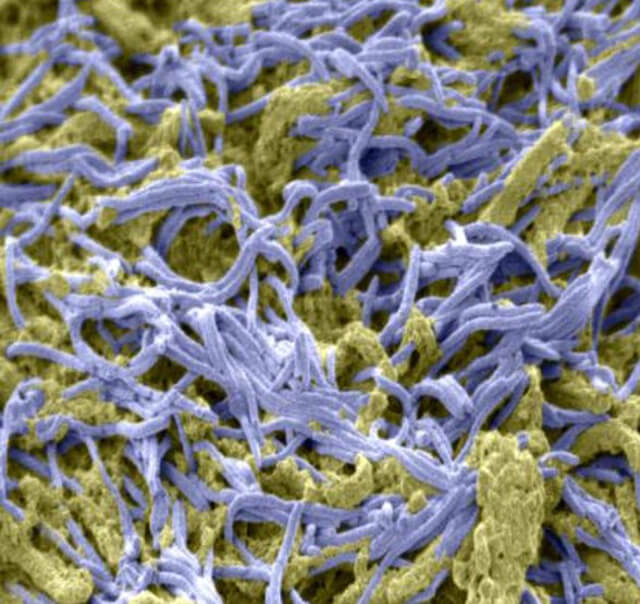

A mass of bacteria (purple) on the surface of colon cancer, mixed with sticky mucus (yellow).

A mass of bacteria (purple) on the surface of colon cancer, mixed with sticky mucus (yellow).Winglee infected five mice with TB. Then, she collected stool samples once a month until the mice died and analyzed the genetic material they contained.

She found that TB changed the bacterial communities significantly. Soon after infection, the diversity of the gut microbiota dropped off. As time went on, the samples became more diverse, but with different bacteria than were there before the mice got TB.

The TB infections were in the lungs, but these differences showed up in the gut. Winglee and her colleagues think that the immune system is sending a signal about infection from lung to gut, which appears to respond by killing off certain species. Their next step is to figure out what aspects of the immune system are contributing to the massacre.

The Parts Bacteria Play

Peterson works with mouse models of intestinal diseases like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colitis. IBD is thought to be an abnormal immune response to bacteria in the gut. The IBD mice Peterson works with have a defect in the lining of the gut, the barrier that keeps bacteria from interacting with the host.

Peterson works with mouse models of intestinal diseases.

Peterson works with mouse models of intestinal diseases.For a study published in May, Peterson and his colleagues studied the shift in the gut bacteria of mice that developed colitis. When they sequenced the mouse guts, they found that the bacterial species Lactobacilis johnsonii was common; it accounted for 30 percent of the bacteria in some of the mice. When mice got colitis, L. johnsonii almost doubled. The researchers thought they might have found a problematic bacterial species. They grew L. johnsonii in the lab, put them into germ-free mice—and found that, if anything, the mice actually got a little healthier.

This highlights one of the challenges of understanding microbiome sequencing data, Peterson says. “Just because something goes up or goes down doesn’t mean it’s bad or good.

“There are a lot of data right now on these relationships between changes in the microbial community and different diseases,” Peterson says. For example, the Human Microbiome Project has spent millions of dollars to catalog microbiome communities in people with different diseases. “The next step is the hard step: trying to figure out all that data.”

No comments:

Post a Comment