Which Way is Up? John F Kennedy Jr plane crash from Fear of Landing

20 Nov 15

25 Comments

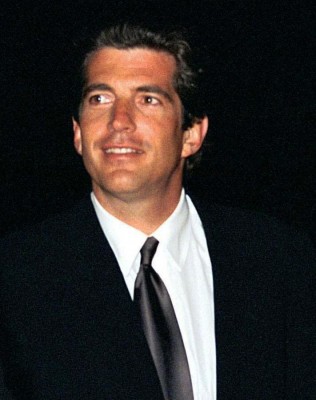

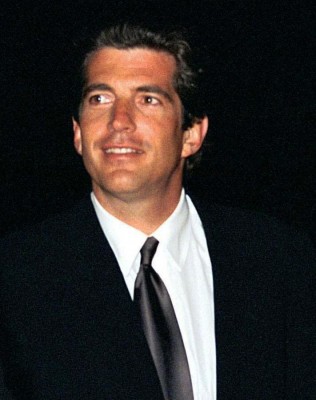

John F. Kennedy Jr. died on the 16th of July 1999, when his

aircraft crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Martha’s

Vineyard, Massachusetts. He was piloting the airplane; his wife and her

sister were in the back.

This

16-year-old accident came up in the comments recently (and if you

aren’t reading the comments here on Fear of Landing, you are missing

half the fun) and I realised I had never read the accident report.

This

16-year-old accident came up in the comments recently (and if you

aren’t reading the comments here on Fear of Landing, you are missing

half the fun) and I realised I had never read the accident report.

The aircraft is coincidentally the same aircraft that I know well, the Piper PA-32 Saratoga II. We sold ours five years ago and I’ll tell you the truth, I still miss it. It’s a fast little single-engine cruiser with low wings and retractable landing gear. This is a small plane that requires a lot of attention – I often struggled with the feeling that I was “running behind the plane,” struggling to keep up.

Here are the details based on the official NTSB report.

The pilot completed his Private Pilot’s Certificate a year before, in April 1998 and got his his high-performance airplane sign-off two months later. He’d bought the Saratoga in April, three months before the accident and received his complex airplane sign-off the month after, required for the Saratoga. He had about 310 hours flying time, 55 of which were at night. However, his experience flying without certified flight instructor (CFI) was only 72 hours.

His flight time in the accident aircraft was about 36 hours, 9.4 of them at night. Of that time, about 3 hours was without a CFI on board and about 0.8 hours at night, including one night landing.

One of his instructors described his aeronautical abilities as average for his level of experience. One friend described him as over-confident.

About six weeks before the flight, the pilot fractured his left ankle in a hang gliding accident.

He’d flown to Martha’s Vineyard just two week’s earlier with the CFI that he regularly used as a safety pilot. It was a night flight in IMC conditions. The CFI said that the flight was uneventful and that the pilot seemed competent with the autopilot. Because of the pilot’s ankle injury, the CFI needed to taxi the aircraft and assist the pilot with the landing.

An employee at the Fixed Base Operator (FBO) at CDW called the pilot at around 13:00 that day to verify that the pilot was intending to fly the Saratoga that weekend. The pilot confirmed that he was planning to fly and would arrive at the airport between 17:30 and 18:00. The employee told the pilot that he would leave the Saratoga parked outside of the hangar.

They were further delayed by traffic and didn’t arrive at the airport by 18:00 as planned.

The pilot, or someone using his code, had made two weather requests from WSI’s PILOTbrief website, one at 18:33 for a radar image and then again at 18:34 for a route friefing from TEB (Teterboro airport) to HYA (Hyannis) with MVY (Martha’s Vineyard) as an alternate. The weather information he received included the fact that at all the airports in the area, visibility was low.

It was much later that evening when the pilot and one of the female passengers were seen loading the aircraft with luggage. Most of the staff of the FBO had left, although the employee who looked after the pilot’s plane was still there. He’d also intended to fly to Martha’s Vineyard that evening but changed his plans after getting the weather report.

Although the sun had set at 20:14, during civil twilight, the illumination is enough that you can see the horizon and make out terrestrial objects. This is the time when Venus is clearly visible without the other stars, hence being known as the “evening star”. This is called “lighting-up time” in the UK and is when car drivers must turn on their headlights. It was a hazy night and the moon was just above the horizon, providing very little light.

At 20:34, the pilot contacted the ground controller. “…Saratoga niner two five three november ready to taxi with mike. Right turnout northeast bound.”

He’s identified himself with his call sign, N9253N and confirmed that he’s picked up Information Mike from Automatic Terminal Service Information recording, which was the latest airfield information. His plan was to turn right after take-off and head north-east.

“Make it a right downwind departure then.”

The pilot acknowledged the instruction saying “right downwind, departure two two.”

The aircraft departed Caldwell Airport at 20:40.

There were no further communications between the pilot and air traffic control. All additional information about the flight is based on radar data.

The flight proceeded normally at first, continuing northeast and remaining below 2,000 feet. At about eight miles northwest of the Westchester County Airport (HPN), White Plains, New York, the aircraft turned north over the Hudson River and began to climb. After continuing north for about six miles, the aircraft turned east. About six miles northeast of Westchester County Airport, the aircraft reached 5,500 feet. The current course was in a direct line to Martha’s Vineyard.

NOTE: My summary of night flying in the US is incorrect and you do have to keep it up-to-date the same as you do with a JAR licence. See the comments for more information and sorry for the confusion!

Night flying is an interesting phenomenon. As a pilot with a JAR licence, I have to get a separate night rating to fly after civil twilight and keep it up-to-date with at least one night take-off and landing every 90 days if I wish to take passengers.

In the US, however, there is no separate rating for night flying and there are no separate requirements for the pilot who wishes to fly with passengers at night.

The difference is that at night, you lose many of your outside visual references and you must rely on flight instruments.

The FAA Airplane Flying Handbook warns of the hazards:

Here’s the transcript:

The event took place outside of New York class B and Westchester

County airport class D airspace, and neither the controller nor the

flight crew reported the issue. However, the radar data makes it clear

that the “traffic” was N9253N.

On that night over the Atlantic, the pilot of the Saratoga may as well have been flying through cloud. It was dark, over water, and the airport lights were not visible in the haze. He had no visual reference whatsoever.

The Saratoga continued to climb, reaching 5,500 feet about six miles northeast of Westchester County Airport. At this stage, you could draw a line from the nose of the aircraft and it would cross Martha’s Vineyard. Instead of following the coastline and then cutting across at the shortest point, the pilot had obviously chosen to fly direct to the island, crossing over a 30-mile (50 km) stretch of water.

Night flying is very different from day flying because of the lack of outside visual references. The FAA is quite clear that VFR night flights should not be made during poor or marginal weather conditions unless the pilot is instrument rated. In addition, crossing large bodies of water at night is specifically mentioned as hazardous, because depth perception and orientation are affected.

600 feet per minute is a standard descent, though I definitely exceeded that in the Saratoga; with no passengers on board, I’d be comfortable descending at 800 feet per minute if I was in a hurry. At this stage, all seemed to be well.

The graveyard spiral is the most common of the vestibular illusions caused by the middle-ear’s balance organ. As you are turning, the fluid inside your ear canal starts moving but, after about 20 seconds, the friction causes the fluid to catch up with the walls of the canal. When this happens, the hairs inside the canal return to their straight-up position, which tells your brain that the turn has stopped even though you are still turning.

I explained a little bit more about these types of illusions on Dan Koboldt’s Science in Sci-fi, Fact in Fantasy series this week: Space Flight in Science Fiction

Your brain tells you that you are still straight and level, even though you are still in the right turn. If you level out the wings, your brain will believe you are turning and banking to the left, although now you are actually straight and level. The compelling belief that you are now turning left will lead you to go back into the right turn.

Pilots are trained to know this, however the illusion cannot be stopped, it can only be ignored. Instrument training teaches you to disbelieve everything you think you know and to trust the instruments. Unfortunately, the certainty that your flight path is not correct is compelling.

So, thirty seconds into the turn at 2,200 feet, the aircraft entered a climb. The aircraft climbed at about 600 feet per minute and the airspeed decreased to about 153 knots. The aircraft stopped the right turn and flew south-east with the wings level, increasing the airspeed back to 160 knots.

They had been descending towards Martha’s Vineyard. There was no reason to stop the descent, no reason to climb. The loss of airspeed means that the pilot did not adjust the power to take into account the change in pitch. That means that the course change was either badly executed or worse, completely unintentional.

According to AC 60-4A, “Pilot’s Spatial Disorientation,” tests conducted with qualified instrument pilots indicated that it can take as long as 35 seconds to establish full control by instruments after a loss of visual reference of the earth’s surface. AC 60-4A further says that surface references and the natural horizon may become obscured even though visibility may be above VFR minimums and that an inability to perceive the natural horizon or surface references is common during flights over water, at night, in sparsely populated areas and in low-visibility conditions.

21:39 The aircraft entered a left turn (towards the east) and climbed to 2,600 feet. As it continued in the turn the aircraft began a descent. Soon, the aircraft was descending at 900 feet per minute.

The aircraft stopped turning, flying east now, but continued to descend at 900 feet per minute.

At the end, the aircraft was descending faster than 4,700 feet per minute.

A reason for this may be that the aircraft was upside-down in a downwards spiral and that the pilot tried to pull back, thus accelerating the descent. He would have done this simply because he no longer had no idea which way was up.

There was no emergency call from the plane.

The following day, a piece of luggage washed up. The luggage tag had the name of one of the passengers on it.

The day after that, the search and rescue was downgraded to a recovery. There was no longer any hope of survivors.

The wreckage was finally found in 120 feet (35 metres) of water four days later, about 1,300 feet / 400 metres away from the final recorded radar position. The wings had been torn away in the impact. All three bodies were found near the wrecked fuselage, still strapped to their seats. They would have died the moment the aircraft crashed into the sea.

Based on the impact marks, the aircraft engines and propellers were at high power when it crashed into the sea. There is no evidence of any aircraft failure or malfunctions.

Two of the radios had incorrect frequencies selected for the standby frequencies, which the report notes but does not comment upon. The incorrect frequencies could well mean that the pilot was distracted when he should have been watching his instruments. Possibly, he was distracted just long enough to become disoriented and, when he looked up, everything felt wrong.

Edit: Clarification from a reader in the US:

First, the simple factual error: 14 CFR 61.157 requires pilots who carry passengers at night to have at least 3 night takeoffs and landings in the previous 90 days. Second, although I’m sure this wasn’t your intention, contrasting the JAR night rating with the lack of a US night rating seems to imply that US pilots don’t receive adequate night training. In fact, for a private pilot’s license 61.109 requires at least 3 hours of night training, a 100nm night cross country, 10 night takeoffs and landings, plus 3 hours of instrument training (which isn’t required by at all by JAR, as far as I know). Admittedly, I have no idea what the requirements were at the time JFK Jr got his license, but the current requirements certainly do provide for both night training and night currency.

This

16-year-old accident came up in the comments recently (and if you

aren’t reading the comments here on Fear of Landing, you are missing

half the fun) and I realised I had never read the accident report.

This

16-year-old accident came up in the comments recently (and if you

aren’t reading the comments here on Fear of Landing, you are missing

half the fun) and I realised I had never read the accident report. The aircraft is coincidentally the same aircraft that I know well, the Piper PA-32 Saratoga II. We sold ours five years ago and I’ll tell you the truth, I still miss it. It’s a fast little single-engine cruiser with low wings and retractable landing gear. This is a small plane that requires a lot of attention – I often struggled with the feeling that I was “running behind the plane,” struggling to keep up.

Here are the details based on the official NTSB report.

The pilot completed his Private Pilot’s Certificate a year before, in April 1998 and got his his high-performance airplane sign-off two months later. He’d bought the Saratoga in April, three months before the accident and received his complex airplane sign-off the month after, required for the Saratoga. He had about 310 hours flying time, 55 of which were at night. However, his experience flying without certified flight instructor (CFI) was only 72 hours.

His flight time in the accident aircraft was about 36 hours, 9.4 of them at night. Of that time, about 3 hours was without a CFI on board and about 0.8 hours at night, including one night landing.

One of his instructors described his aeronautical abilities as average for his level of experience. One friend described him as over-confident.

About six weeks before the flight, the pilot fractured his left ankle in a hang gliding accident.

He’d flown to Martha’s Vineyard just two week’s earlier with the CFI that he regularly used as a safety pilot. It was a night flight in IMC conditions. The CFI said that the flight was uneventful and that the pilot seemed competent with the autopilot. Because of the pilot’s ankle injury, the CFI needed to taxi the aircraft and assist the pilot with the landing.

The CFI stated that the pilot had the ability to fly the airplane without a visible horizon but may have had difficulty performing additional tasks under such conditions. He also stated that the pilot was not ready for an instrument evaluation as of July 1, 1999, and needed additional training. The CFI was not aware of the pilot conducting any flight in the accident airplane without an instructor on board. He also stated that he would not have felt comfortable with the accident pilot conducting night flight operations on a route similar to the one flown on, and in weather conditions similar to those that existed on, the night of the accident. The CFI further stated that he had talked to the pilot on the day of the accident and offered to fly with him on the accident flight. He stated that the accident pilot replied that “he wanted to do it alone.”The plan was to fly from Caldwell Airport (formally Essex County Airport, CDW) in New Jersey to Martha’s Vineyard. There, the couple would drop off their passenger and then continue on to Hyannis, Massachusetts where they were attending a family wedding. They’d originally planned to fly over during the day but the passenger for Martha’s Vineyard was delayed at work.

An employee at the Fixed Base Operator (FBO) at CDW called the pilot at around 13:00 that day to verify that the pilot was intending to fly the Saratoga that weekend. The pilot confirmed that he was planning to fly and would arrive at the airport between 17:30 and 18:00. The employee told the pilot that he would leave the Saratoga parked outside of the hangar.

They were further delayed by traffic and didn’t arrive at the airport by 18:00 as planned.

The pilot, or someone using his code, had made two weather requests from WSI’s PILOTbrief website, one at 18:33 for a radar image and then again at 18:34 for a route friefing from TEB (Teterboro airport) to HYA (Hyannis) with MVY (Martha’s Vineyard) as an alternate. The weather information he received included the fact that at all the airports in the area, visibility was low.

ACK 1753: Clear skies; visibility 5 miles in mist; winds 240 degrees at 16 knots.There’s no record of the pilot requesting a weather briefing at the airport before his flight. He did not file a flight plan (and didn’t need to for the flight) which meant that his exact route and expected time of arrival were not known.

CDW 1753: Clear skies; visibility 4 miles in haze; winds 230 degrees at 7 knots.

HYA 1756: Few clouds at 7,000 feet; visibility 6 miles in haze; winds 230 degrees at 13 knots.

MVY 1753: Clear skies; visibility 6 miles in haze; winds 210 degrees at 11 knots.

It was much later that evening when the pilot and one of the female passengers were seen loading the aircraft with luggage. Most of the staff of the FBO had left, although the employee who looked after the pilot’s plane was still there. He’d also intended to fly to Martha’s Vineyard that evening but changed his plans after getting the weather report.

Another pilot had flown from Bar Harbor, Maine, to Long Island, New York, and crossed the Long Island Sound on the same evening, about 1930. This pilot stated that during his preflight weather briefing

from an FSS, the specialist indicated VMC for his flight. The pilot filed an IFR flight plan and conducted the flight at 6,000 feet. He stated that he encountered visibilities of 2 to 3 miles throughout the flight because of haze. He also stated that the lowest visibility was over water, between Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and eastern Long Island. He stated that he did not encounter any clouds below 6,000 feet.

20:25 A phone call is logged from a passenger mobile

phone. By the time the aircraft was loaded and they were ready to

depart, it was half past eight and getting dark. The two sisters sat at

the back, facing the rear of the aircraft. Although the sun had set at 20:14, during civil twilight, the illumination is enough that you can see the horizon and make out terrestrial objects. This is the time when Venus is clearly visible without the other stars, hence being known as the “evening star”. This is called “lighting-up time” in the UK and is when car drivers must turn on their headlights. It was a hazy night and the moon was just above the horizon, providing very little light.

At 20:34, the pilot contacted the ground controller. “…Saratoga niner two five three november ready to taxi with mike. Right turnout northeast bound.”

He’s identified himself with his call sign, N9253N and confirmed that he’s picked up Information Mike from Automatic Terminal Service Information recording, which was the latest airfield information. His plan was to turn right after take-off and head north-east.

20:38:32 He reported ready to take off from runway 22

and was told he was clear to take off. The tower controller asked if he

was heading towards Teterboro, New Jersey. “No sir,” said the pilot.

“I’m … actually I’m heading a little uh north of it, uh eastbound.”“Make it a right downwind departure then.”

The pilot acknowledged the instruction saying “right downwind, departure two two.”

The aircraft departed Caldwell Airport at 20:40.

There were no further communications between the pilot and air traffic control. All additional information about the flight is based on radar data.

20:41 A radar target transmitting a visual flight rules

(VFR) code was observed about a mile southwest of Caldwell Airport at an

altitude of 1,300 feet. This was N9253N on its way to Martha’s

Vineyard.The flight proceeded normally at first, continuing northeast and remaining below 2,000 feet. At about eight miles northwest of the Westchester County Airport (HPN), White Plains, New York, the aircraft turned north over the Hudson River and began to climb. After continuing north for about six miles, the aircraft turned east. About six miles northeast of Westchester County Airport, the aircraft reached 5,500 feet. The current course was in a direct line to Martha’s Vineyard.

20:47 Civil twilight ended. This is when nautical

twilight begins, during which the horizon should still be visible

although land features and sea are not unless they are artificially

illuminated. NOTE: My summary of night flying in the US is incorrect and you do have to keep it up-to-date the same as you do with a JAR licence. See the comments for more information and sorry for the confusion!

Night flying is an interesting phenomenon. As a pilot with a JAR licence, I have to get a separate night rating to fly after civil twilight and keep it up-to-date with at least one night take-off and landing every 90 days if I wish to take passengers.

In the US, however, there is no separate rating for night flying and there are no separate requirements for the pilot who wishes to fly with passengers at night.

The difference is that at night, you lose many of your outside visual references and you must rely on flight instruments.

The FAA Airplane Flying Handbook warns of the hazards:

Crossing large bodies of water at night in single-engine airplanes could be potentially hazardous, not only from the standpoint of landing (ditching) in the water, but also because with little or no lighting the horizon blends with the water, in which case, depth perception and orientation become difficult. During poor visibility conditions over water, the horizon will become obscure, and may result in a loss of orientation. Even on clear nights, the stars may be reflected on the water surface, which could appear as a continuous array of lights, thus making the horizon difficult to identify.

20:49 American Airlines flight 1484 was approaching

Westchester County Airport and began descending from 6,000 feet as per

the request of the New York approach controller. Here’s the transcript:

| 20:52 | New York approach controller | American fourteen eighty four traffic one o’clock and five miles eastbound two thousand four hundred, unverified, appears to be climbing. |

| 20:52 | American Airlines flight 1484 | American fourteen eighty four, we’re looking. |

| 20:52 | New York approach controller | Fourteen eighty four, Traffic one o’clock and uh three miles twenty eight hundred now, unverified. |

| 20:53 | American Airlines flight 1484 | Yes, we have uh (unintelligible)… I think we have him here. |

| 20:53 | American Airlines flight 1484 | I understand he’s not in contact with you or anybody else. |

| 20:53 | New York approach controller | Uh, nope doesn’t… not talking to anybody. |

| 20:53 | American Airlines flight 1484 | Seems to be climbing through uh thirty one hundred now we just got a traffic advisory here. |

| 20:53 | New York approach controller | Uh that’s what it looks like. |

| 20:53 | American Airlines flight 1484 | Uh, we just had a… |

| 20:54 | New York approach controller | American fourteen eighty four you can contact tower nineteen seven. |

| 20:54 | American Airlines flight 1484 | Nineteen seven. Uh we had a resolution advisory seemed to be a single engine Piper er Comanche or something. |

| 20:54 | New York approach controller | Roger. |

On that night over the Atlantic, the pilot of the Saratoga may as well have been flying through cloud. It was dark, over water, and the airport lights were not visible in the haze. He had no visual reference whatsoever.

The Saratoga continued to climb, reaching 5,500 feet about six miles northeast of Westchester County Airport. At this stage, you could draw a line from the nose of the aircraft and it would cross Martha’s Vineyard. Instead of following the coastline and then cutting across at the shortest point, the pilot had obviously chosen to fly direct to the island, crossing over a 30-mile (50 km) stretch of water.

21:28 Nautical twilight ended. This is the point at which navigation by horizon is no longer possible. Night flying is very different from day flying because of the lack of outside visual references. The FAA is quite clear that VFR night flights should not be made during poor or marginal weather conditions unless the pilot is instrument rated. In addition, crossing large bodies of water at night is specifically mentioned as hazardous, because depth perception and orientation are affected.

21:33 The aircraft began to descend for Martha’s

Vineyard, about 34 miles west of the airfield. It was travelling at

about 160 knots indicated airspeed and descending between 400 and 800

feet per minute, a very reasonable and comfortable descent in that

aircraft. 21:37 The aircraft passed through 3,000 feet at a steady descent rate of 600 feet per minute.600 feet per minute is a standard descent, though I definitely exceeded that in the Saratoga; with no passengers on board, I’d be comfortable descending at 800 feet per minute if I was in a hurry. At this stage, all seemed to be well.

21:38 The aircraft started to bank, right wing down,

toward a southerly direction. About 30 seconds later, it stopped its

descent and started a gentle climb, coming out of the right turn at the

same time.The graveyard spiral is the most common of the vestibular illusions caused by the middle-ear’s balance organ. As you are turning, the fluid inside your ear canal starts moving but, after about 20 seconds, the friction causes the fluid to catch up with the walls of the canal. When this happens, the hairs inside the canal return to their straight-up position, which tells your brain that the turn has stopped even though you are still turning.

I explained a little bit more about these types of illusions on Dan Koboldt’s Science in Sci-fi, Fact in Fantasy series this week: Space Flight in Science Fiction

Your brain tells you that you are still straight and level, even though you are still in the right turn. If you level out the wings, your brain will believe you are turning and banking to the left, although now you are actually straight and level. The compelling belief that you are now turning left will lead you to go back into the right turn.

Pilots are trained to know this, however the illusion cannot be stopped, it can only be ignored. Instrument training teaches you to disbelieve everything you think you know and to trust the instruments. Unfortunately, the certainty that your flight path is not correct is compelling.

So, thirty seconds into the turn at 2,200 feet, the aircraft entered a climb. The aircraft climbed at about 600 feet per minute and the airspeed decreased to about 153 knots. The aircraft stopped the right turn and flew south-east with the wings level, increasing the airspeed back to 160 knots.

21:39 The aircraft levelled off at 2,500 feet and continued in a south-easterly direction. They had been descending towards Martha’s Vineyard. There was no reason to stop the descent, no reason to climb. The loss of airspeed means that the pilot did not adjust the power to take into account the change in pitch. That means that the course change was either badly executed or worse, completely unintentional.

According to AC 60-4A, “Pilot’s Spatial Disorientation,” tests conducted with qualified instrument pilots indicated that it can take as long as 35 seconds to establish full control by instruments after a loss of visual reference of the earth’s surface. AC 60-4A further says that surface references and the natural horizon may become obscured even though visibility may be above VFR minimums and that an inability to perceive the natural horizon or surface references is common during flights over water, at night, in sparsely populated areas and in low-visibility conditions.

21:40 The moon was starting to rise. 21:45 A pilot with planned stopover at Martha’s Vineyard landed uneventfully at the airfield.He stated that the entire flight was conducted under VFR, with a visibility of 3 to 5 miles in haze.Another pilot spoke to the NTSB about conditions that night.

He stated that, over land, he could see lights on the ground when he looked directly down or slightly forward; however, he stated that, over water, there was no horizon to reference. He stated that he was not sure if he was on top of the haze layer at 7,500 feet and that, during the flight, he did not encounter any cloud layers or ground fog during climb or descent. He further stated that, between Block Island and MVY, there was still no horizon to reference. He recalled that he began to observe lights on Martha’s Vineyard when he was in the vicinity of Gay Head. He stated that, before reaching MVY, he would have begun his descent from 7,500 feet and would have been between 3,000 and 5,000 feet over Gay Head (the pilot could not recall his exact altitudes). He did not recall seeing the Gay Head marine lighthouse. He was about 4 miles from MVY when he first observed the airport’s rotating beacon. He stated that he had an uneventful landing at MVY about 2145.

He reported that above 14,000 feet, the visibility was unrestricted; however, he also reported that during his descent to Nantucket, when his global positioning system (GPS) receiver indicated that he was over Martha’s Vineyard, he looked down and “…there was nothing to see. There was no horizon and no light….I turned left toward Martha’s Vineyard to see if it was visible but could see no lights of any kind nor any evidence of the island…I thought the island might [have] suffered a power failure.”Meanwhile, the flight path of the Saratoga is getting ever more erratic.

He also stated, “I had no visual reference of any kind yet was free of any clouds or fog.”

21:39 The aircraft entered a left turn (towards the east) and climbed to 2,600 feet. As it continued in the turn the aircraft began a descent. Soon, the aircraft was descending at 900 feet per minute.

The aircraft stopped turning, flying east now, but continued to descend at 900 feet per minute.

20:40:15 Still descending, the aircraft entered a right

turn. As the turn rate increased, the descent rate and the airspeed also

increased. At the end, the aircraft was descending faster than 4,700 feet per minute.

A reason for this may be that the aircraft was upside-down in a downwards spiral and that the pilot tried to pull back, thus accelerating the descent. He would have done this simply because he no longer had no idea which way was up.

21:40:34 The last radar contact with the aircraft showed it at 1,100 feet. There was no emergency call from the plane.

21:40 Radar contact with the aircraft was lost. The last radar signal showed it as 1,100 feet flying away from Martha’s Vineyard.The following day, a piece of luggage washed up. The luggage tag had the name of one of the passengers on it.

The day after that, the search and rescue was downgraded to a recovery. There was no longer any hope of survivors.

The wreckage was finally found in 120 feet (35 metres) of water four days later, about 1,300 feet / 400 metres away from the final recorded radar position. The wings had been torn away in the impact. All three bodies were found near the wrecked fuselage, still strapped to their seats. They would have died the moment the aircraft crashed into the sea.

Based on the impact marks, the aircraft engines and propellers were at high power when it crashed into the sea. There is no evidence of any aircraft failure or malfunctions.

Two of the radios had incorrect frequencies selected for the standby frequencies, which the report notes but does not comment upon. The incorrect frequencies could well mean that the pilot was distracted when he should have been watching his instruments. Possibly, he was distracted just long enough to become disoriented and, when he looked up, everything felt wrong.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident as follows:A 2004 study found that the average life expectancy of a non-instrument-rated pilot who flies into clouds or instrument conditions is 178 seconds. Not quite three minutes. This particular accident reminds us that it isn’t always obvious when instrument conditions apply.

- The pilot’s failure to maintain control of the airplane during a descent over water at night, which was a result of spatial disorientation. Factors in the accident were haze, and the dark night.

Edit: Clarification from a reader in the US:

First, the simple factual error: 14 CFR 61.157 requires pilots who carry passengers at night to have at least 3 night takeoffs and landings in the previous 90 days. Second, although I’m sure this wasn’t your intention, contrasting the JAR night rating with the lack of a US night rating seems to imply that US pilots don’t receive adequate night training. In fact, for a private pilot’s license 61.109 requires at least 3 hours of night training, a 100nm night cross country, 10 night takeoffs and landings, plus 3 hours of instrument training (which isn’t required by at all by JAR, as far as I know). Admittedly, I have no idea what the requirements were at the time JFK Jr got his license, but the current requirements certainly do provide for both night training and night currency.

Category:

Accident Reports

Sad,JFK jr. seemed a nice guy and the family had already gone though such terrible times.

Of course, admitting that something, anything, would be outside the competence of a Kennedy would have been unthinkable. So with insufficient experience he nevertheless departed on this doomed flight.

Sad, very sad.

I believe the type of turbulence they experienced made that small plane literally impossible to fly and if by chance someone (pilot) hadn’t buckled in their seat and hit that turbulence wall, that turbulence was violent enough to throw anyone around a small plane like a pinball.

JFK Jr may have been knocked unconscious along with the others but even if it was just the pilot, I doubt anyone else could get to the controls, move jfk, and get ahold of plane control. by that time they were probably in a spiral.

I believe that would have happened early evening when there was still light, let alone add darkness, fog and turbulence of that nature together.

ask any pilot who flew that afternoon or evening through that area and they’ll probably remember that turbulence and agree that an advisory should have been placed for small aircraft that evening.

you can forget your conspiracy theories because this is probably close to what happened to that ill-fated flight. I experienced that turbulence first-hand.

r. botts (codeblue@hotmail.com)

I couldn’t find any reference to whether or not the pilot was night current in the accident report.

It would have been two buttons to press to set the autopilot to straight and level flight and, until he was in real difficulties, it would have taken over, levelled the wings and given him time to think. The Saratoga is an unforgiving plane to hand-fly; with the auto-pilot on it’s a doddle.

have you read any of the blogs from Andy Green, the RAF pilot who will be driving the Bloodhound supersonic land speed car, as he did for Thrust SSC? I thought that in one of them he described the optical illusion of such acceleration and deceleration but could find it, maybe it was a video piece. Even with a visual reference which you know is perfectly level, he says that while accelerating the brain tells you that you are driving up a steep hill, and when you decelerate it you are heading even more steeply downhill. I hope I remembered that correctly.

Definitely one place where you do NOT want to go flying!

Keep up the fascinating blogs.

Regards, Martin.

Once on the ground I asked the PIC about what I felt and he gave me a quick intro into spacial disorientation. I asked him if he got the same feelings while we were flying and to my horror said ‘yes’.

Lesson learned, don’t try to fly vfr in imc. Rated or not it’s a gamble many lose.

And, if visibility was limited when approaching Westchester County Airport the logical thing to do is fly over Long Island where you could

easily stop at the Hamptons for a bite to eat at a good restaurant or sleep over until the next day. The hop from the tip of Long Island to Martha’s Vineyard is about 30 miles and at 200 MPH? Hmmm?

30 Miles / 100 Miles Per Hour__the Miles cancel out and the Hour flips

up so we have 30/100 Hours? 3/10 Hour? 0.3Hours x 60 Minutes/Hour

= 0.3 x 60 = about 20 minutes? I’m so bad at math. 20 Minutes over

the water and then right into Martha’s Vineyard? Hmmm?

And, with all that time under his belt I’m sure his eyes were always scanning the instruments and any pilot worth his salt will tell you that the first thing you read up on is__how to stop a plane from crashing. It is a survival thing just like driving a car__what do I do if I’m on ice or an oily road and my car starts to skid? Every man who owns a car knows how to get his car out of a skid and gain control of the car. Common__this plane was being flown by the sister Lauren because JFK Jr was dead or they faked the crash. Also, GPS and even Google Maps would have given him accurate Position so I don’t buy the “he was lost in the cloud or fog explanation”. I can instruct Howard Stern and Robin Quivers how to fly the Piper Saratoga both VFR and IFR in 1/2 hour and then take them up and put blind folds on them and spin the plane and they would be able to tell me what to do in order to gain control of the plane. Simply as that. The Piper Saratoga is easy to fly__this is no Lear Jet or Mooney!

I also gave the same information to many other celebrities including Princess Diana and they either died in mysterious transportation accidents or died of cancer or strange diseases which indicates the US Military and the Jews were cleaning people!

Of course if you are a member of the Jewish CIA and are planning to put a hit on me for exposing this__I’m mentally ill and need medications. Ha Ha Ha!

.i can see me doing the same uffdah .

I can see me doing the exact same . Its just not natural to believe things out side of one self takes time and training uffdah .

However in my opinion, in this kind of plane where the pilot has clearly become disorientated, he would have been spending 100% of his brain power trying to work out what was going wrong. He would not be thinking about crashing, he would be thinking about solving his problem without ever actually deciphering what the problem really was.

As for the passengers, They would not have got into the plane unless they thought the pilot was competent. Thus they would not have known they were going to crash; they would also have felt that there was a problem that the pilot was dealing with.

Just my opinion, of course. No one will ever know for certain.