Summing Up Russia’s Real Nuclear Fears

By Jonathan Marshall

The conflicts between Washington and Moscow keep on growing: Ukraine and Syria, rival war games, “hybrid” wars and “cyber-wars.” Talk of a new Cold War doesn’t do justice to the stakes.

“My bottom line is that the likelihood of a nuclear catastrophe today is greater than it was during the Cold War,” declares former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry.

If a new Trump administration wants to peacefully reset relations with Russia, there’s no better way to start than by canceling the deployment of costly new ballistic missile defense systems in Eastern Europe. One such system went live in Romania this May; another is slated to go live in Poland in 2018. Few U.S. actions have riled President Putin as much as this threat to erode Russia’s nuclear deterrent.

Only last month, at a meeting in Sochi with Russian military leaders to discuss advanced new weapons technology, Putin vowed, “We will continue to do all we need to ensure the strategic balance of forces. We view any attempts to change or dismantle it, as extremely dangerous. Our task is to effectively neutralize any military threats to Russia’s security, including those posed by the newly-deployed strategic missile defense systems.”

Putin accused unnamed countries — obviously led by the United States — of “nullifying” international agreements on missile defense “in an effort to gain unilateral advantages.”

Moscow has reacted to this perceived threat with more than mere words. It is developing new and deadlier nuclear missiles, including the SS-30, to counter U.S. defenses. It has rebuffed new arms control negotiations. And it has provocatively stationed nuclear-capable Iskander missiles in the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad to “target . . . the facilities that . . . start posing a threat to us,” as Putin put it last month.

If a new arms race is underway, it’s not for lack of warning. The Russians have voiced their concerns about missile defenses for years and years, without any serious acknowledgment from Washington. From their vantage point, the apparent bad faith of successive U.S. administrations, Democratic as well as Republican, is a flashing red light to which they had to respond.

Russia’s Nightmare

From the earliest days of President Reagan’s Strategic Defense (“Star Wars”) Initiative to make ballistic missiles “impotent and obsolete,” an alarmed Moscow has viewed U.S. efforts to build a missile shield as a long-term threat to their nuclear deterrent.

President Reagan meets with Vice President George H.W. Bush on Feb. 9, 1981. (Photo credit: Reagan Presidential Library.)

Writing in Foreign Affairs magazine, Ivanov warned that such a move would set back recent progress in Russian-U.S. relations and destroy “30 years of efforts by the world community” to reduce the danger of nuclear war. Russia would be forced, against its desire for international cooperation, to build up its own forces in response. The arms race would be back in full force — leaving the United States less secure, not more.

But with Russia still reeling from the neoliberal “shock therapy” that it suffered through during the 1990s, the neoconservatives (then in charge of U.S foreign policy) were confident of winning such an arms race. In 2002, President Bush adopted a National Security Strategy that explicitly called for U.S military superiority over every other power. To that end, he called on the Pentagon to develop a ground-based missile defense system within two years.

Since then, that program has lined the pockets of major U.S. military contractors without achieving any notable successes. Critics – including the U.S. General Accountability Office, National Academy of Sciences and Union of Concerned Scientists – have blasted the program for failing more than half of its operational tests. Today, after the expenditure of more than $40 billion, it enjoys bipartisan support mainly as a jobs program.

Russia fears, however, that it’s only a matter of time before the U.S. perfects its missile shield technology enough to erode the deterrent capabilities of Moscow’s nuclear arsenal.

Promoting U.S. Nuclear Primacy

That specter was highlighted in 2006 when two U.S. strategic arms experts declared in the pages of the establishment-oriented Foreign Affairs that the age of nuclear deterrence “is nearing an end. Today, for the first time in almost 50 years, the United States stands on the verge of attaining nuclear primacy. It will probably soon be possible for the United States to destroy the long-range nuclear arsenals of Russia or China with a first strike. . . . Unless they reverse course rapidly, Russia’s vulnerability will only increase over time.”

The authors, Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, added, “Washington’s pursuit of nuclear primacy helps explain its missile defense strategy.” Missile defense, they pointed out, is not the same as population defense. No conceivable defense could truly protect American cities against an all-out attack by Russia, or even China. Rather, a leaky shield “would be valuable primarily in an offensive context, not a defensive one — as an adjunct to a U.S. first-strike capability, not as a standalone shield.”

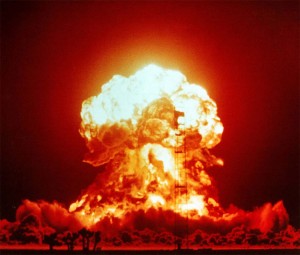

“If the United States launched a nuclear attack against Russia (or China),” they explained, “the targeted country would be left with a tiny surviving arsenal — if any at all. At that point, even a relatively modest or inefficient missile-defense system might well be enough to protect against any retaliatory strikes, because the devastated enemy would have so few warheads and decoys left.”

As if to make that scenario a reality, the Bush administration soon announced plans to install an anti-missile base in Poland and a radar control center in the Czech Republic — ostensibly to counter a nuclear threat from Iran. No matter that Iran had neither nuclear weapons nor long-range ballistic missiles — or that Washington had rebuffed Russia’s offer to cooperate on building missile defenses closer to Iran. No, Moscow was supposed to believe President Bush’s assurance that “Russia is not the enemy.”

Republican hawks in Congress didn’t get the message. Said Rep. Trent Franks of Arizona, “This is not just about missile defense; this is about demonstrating to Russia that America is still a nation of resolve . . . and we’re not going to let Russian expansionism intimidate everyone.”

Yet when Russian officials reacted with alarm, and warned of the potential for a “new Cold War,” American news accounts accused them of being “bellicose.”

Obama Blows Up the Reset Button

Taking office in 2009, President Obama promised a new era of nuclear sanity. Again, the Russians pleaded for an end to the missile defense program in Eastern Europe. Privately, they expressed a new and genuine concern — that a future U.S. administration could secretly fit interceptor rockets with nuclear warheads and use them to “decapitate” Russia’s top leadership with “virtually no warning time.” Russia’s response: retaliate at the first sign of an incoming strike, without hesitating to check if it’s a false alarm.

President

Barack Obama meets with President Vladimir Putin of Russia on the

sidelines of the G20 Summit in Antalya, Turkey, Nov. 15, 2015. National

Security Advisor Susan E. Rice listens at left. (Official White House

Photo by Pete Souza)

Obama’s “reset button” was the first casualty of his nuclear policy. In 2011, a despairing President Dmitry Medvedev warned that Russia would have no choice but to respond exactly as Putin has done, by upgrading the offensive capabilities of Russian nuclear missiles and deploying Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad. Still to come may be a Russian withdrawal from the New START treaty, which Secretary of State Hillary Clinton claimed as her greatest accomplishment in the field of arms control.

President Obama never intended to expand his limited missile defense program into an existential threat to Russia’s nuclear deterrent, but he opened that door. Exactly as Moscow has long feared, hawks in Congress now are chomping at the bit to spend what it takes to build an all-out missile defense system, which former Defense Secretary Robert Gates warned would be “enormously destabilizing not to mention unbelievably expensive.”

One 2003 study pegged the possible cost of a full defensive shield covering the United States at more than $1 trillion. But that’s a small price compared to what could happen if a jittery Russian military command, armed to the teeth with nuclear missiles set on hair-trigger alert to counter a successful U.S. first strike, receives a false warning of just such an attack. Such a scenario has happened more than once.

One of these days such a mistake may prompt an all-out Russian nuclear launch — and then, not even a full missile defense will spare the United States, and much of the world, from devastation.

Jonathan Marshall is author of many recent articles on arms issues, including “How World War III Could Start,” “NATO’s ProvocativeAnti-Russian Moves,” “Escalations in a New Cold War,” “Ticking Closer to Midnight,” and “Turkey’s Nukes: A Sum of All Fears.”

No comments:

Post a Comment