High Crimes and Misdemeanors

Graft and Oil: How Teapot Dome Became the Greatest Political Scandal of Its Time

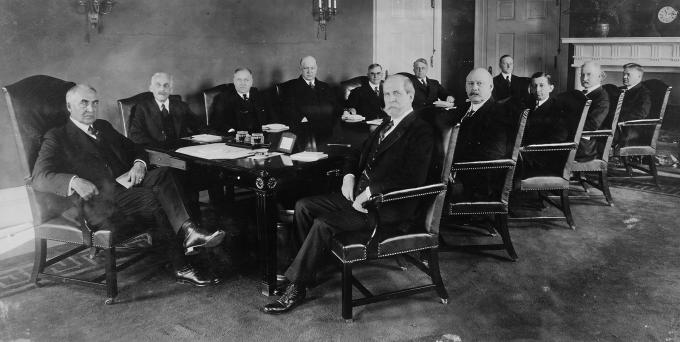

Warren

G. Harding (far left) with his Cabinet, including Albert Fall (2nd from

right) who perpetrated the Teapot Dome scandal, 1921. (Library of

Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Warren

G. Harding (far left) with his Cabinet, including Albert Fall (2nd from

right) who perpetrated the Teapot Dome scandal, 1921. (Library of

Congress Prints and Photographs Division)Teapot Dome is a geological feature in Wyoming, named for nearby Teapot Rock, and the site of an oil field. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson designated that oil deposit as Naval Oil Reserve Number 3 (reserves Number 1 and Number 2, in Elk Hills and Buena Vista Hills, California, respectively, had been similarly identified by President William Howard Taft in 1912). These reserves were created to guarantee that the Navy would have a sufficient supply of oil in wartime. However, their establishment was controversial—oil interests believed that the reserves were unnecessary and could be developed privately. In addition, private wells surrounded the naval reserve fields, siphoning off their underground deposits.

That was the situation facing Albert Fall, one of President Harding’s poker pals, when Harding appointed him as Secretary of the Interior in 1921. As a lawyer in New Mexico Territory, Fall had represented mining and timber companies and had invested in mining himself. As a US senator from New Mexico after 1912, he’d shown little interest in the conservation movement, and conservationists, led by Harry Slattery and Gifford Pinchot, viewed him as hostile to their ideas. When Fall tried to open Alaska’s oil, coal, and timber to extensive private development, the conservationists were quick to organize and defeat his plans. Similarly, when Fall tried to move the National Forests and federal Forestry Service under his control at the Department of the Interior, the conservationists blocked him. In their efforts, conservationists could count on help from a number of progressives in Congress, notably Senator Robert La Follette, a leader of the progressive wing of the Republican Party.

Stymied in his efforts to acquire more control over western natural resources and make them more easily available to developers, Fall turned to the naval oil reserves. He persuaded Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby and President Harding to transfer the naval oil reserves to the Interior Department. He then secretly, and without competitive bidding, leased the Teapot Dome oil rights to Harry Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Company and the Elk Hills oil rights to the Pan-American Petroleum Company, owned by Edward Doheny, a longtime friend of Fall’s. When the news became public in April 1922, conservationists and small oil producers in Wyoming, who objected to the secrecy and lack of competitive bidding, raised a storm of protest. La Follette called for a Senate investigation, and the Senate approved the resolution.

Fall argued that his actions were perfectly reasonable and beneficial to the Navy, since the reserves were threatened by privately owned oil wells that were draining the Navy’s oil. Granting a single lease to pump the reserved oil, Fall reasoned, was the most efficient means of saving it. The leases required Sinclair and Doheny to calculate royalties for the oil they pumped from the naval reserves, and use the royalties to construct and fill fuel storage facilities for the Navy in California, Pearl Harbor (Hawaii), and elsewhere. Sinclair was also to construct a pipeline from Wyoming to Kansas City, which would be available for other oil producers as well. Fall claimed that secrecy, and hence no competitive bidding, was necessary because the storage facilities could be targets in a war.

When the Senate opened its investigation, Fall delivered a truckload of documents to the committee, snarling the investigators in a mass of paper. He then resigned from office in January 1923. The investigation, led by Senator Thomas Walsh, Democrat of Montana, with assistance from Slattery, finally got underway in October of that year. Though nothing seemed objectionable in the materials delivered by Fall, Walsh began to dig into reports of improvements to Fall’s ranch. In January 1924, testifying before the committee, Doheny revealed that he had loaned Fall $100,000, and that his son, Edward Doheny Jr., together with his son’s close friend Hugh Plunkett, had delivered the cash to Fall in a satchel. However, Doheny denied that the loan had any connection to the Elk Hills lease. Similarly, Sinclair acknowledged that he’d given Fall some livestock but denied any connection to Teapot Dome. Congress thereupon asked the President to take action to cancel the leases and name special counsel to investigate and prosecute those responsible for any wrongdoing.

Harding’s sudden death in August 1923 released him from mounting an investigation of his scandal-plagued administration. He had appointed friends such as Fall to high positions in the government where many of them took bribes, embezzled government money, and committed fraud. He died before investigators could determine the full extent of his cronies’ corrupt activities.

President Calvin Coolidge, who had become president when Harding died, announced he would appoint two special prosecutors, one Democrat and one Republican, to take over the investigation. Owen J. Roberts, a prominent lawyer and future Supreme Court Justice, was the Republican; Atlee Pomerene, a former US Senator from Ohio, was the Democrat. Under their leadership, the investigation discovered that one of Sinclair’s companies had transferred $233,000 in Liberty Bonds (bonds issued by the federal government during World War I) to Fall’s son-in-law, and that Sinclair had also contributed substantially to the Republican Party.

As the Teapot Dome scandal unfolded, Democrats gleefully planned a 1924 presidential campaign against Republican corruption. Teapot Dome was only the most dramatic example of corruption by Harding’s appointees. Other scandals had emerged in the Veterans Bureau and in the office of the Alien Property Custodian (responsible for the property of Germans and other enemy aliens during World War I). One scandal implicated Harding’s Attorney General, Harry Daugherty. Coolidge, however, provided the Republicans with an image of flinty integrity, and his actions in appointing the special prosecutors, in demanding the resignation of Daugherty and Denby, and in naming the highly regarded Harlan Fiske Stone as Daugherty’s successor seemed to demonstrate that he would not tolerate corruption in his administration and that his standards for Cabinet appointments were much higher than Harding’s had been.

The Democrats proved to have oil problems of their own. Doheny was a Democrat who had contributed to the Democratic Party; through his various business enterprises, he had hired a number of prominent Democrats at various times. During the Senate hearings, a Republican Senator led Doheny to reveal that four previous members of Woodrow Wilson’s Cabinet, all important leaders of the Democratic Party, had been on his payroll after leaving public office. Most significantly for the Democrats, Doheny had paid William Gibbs McAdoo $50,000 per year for several years as a legal retainer. McAdoo, the leading Democratic presidential prospect and well known as a progressive, was now tainted by oil money. Though a major problem, Doheny’s money was not the only problem with McAdoo’s campaign, and he failed to secure the nomination. Instead, the Democrats nominated John W. Davis, a conservative lawyer who specialized in representing corporations. As a result, most progressives in both parties supported the third-party candidacy of Robert La Follette. Coolidge won easily. In the end, though both Republicans and Democrats had tried to use Teapot Dome to embarrass their opponents, neither party drew much advantage from the events.

By the time Walsh’s investigation finally wound down, he had found only circumstantial evidence against Fall. Roberts and Pomerene, however, found additional evidence and filed a total of eight cases, two civil and six criminal. In 1929, Fall was convicted on charges of accepting a bribe from Doheny—the only guilty verdict in the Teapot Dome case. Fall, the first Cabinet member convicted of a crime committed while in office, was fined $100,000 and sentenced to a year in prison. Doheny, however, was acquitted of offering the same bribe to Fall; both men always insisted that the $100,000 was a loan, and Doheny eventually foreclosed on Fall’s ranch. With Fall now destitute, his fine was excused. After all appeals failed, he arrived at prison in 1931 but was released after nine months due to poor health. In 1929, Doheny’s son was murdered by Plunkett, who then committed suicide; Plunkett may have feared that he’d be sent to prison for helping to deliver the cash to Fall.

Like Doheny, Sinclair was acquitted of bribing Fall but served several months in prison for contempt of Congress and contempt of court. Doheny and Sinclair remained wealthy and powerful until their deaths. Doheny is memorialized by Doheny State Beach in California, the Doheny Campus of Mount St. Mary’s College in southern California, the Doheny Library (a memorial to his son) at the University of Southern California, and the Doheny Eye Institute (created by his wife). Sinclair Oil Corporation remains a major supplier of oil and gasoline in twenty-two states.

In 1924, in reaction to the Teapot Dome scandal, President Coolidge set up the Federal Oil Conservation Board to encourage closer coordination in oil production between the federal government and the oil industry. Its activities laid the basis for a loose interstate oil cartel that set crude oil prices until 1973.

Walsh’s work set important legal precedents for the power of Congressional investigating committees. Sinclair had refused to answer some questions before the Senate committee on the grounds that Congress had no jurisdiction over his private affairs. In Sinclair v. United States in 1929, the Supreme Court upheld the right of the Senate to investigate the effect of the laws it passed. Earlier, in a spin-off investigation from Teapot Dome, Attorney General Daugherty’s brother, Mally Daugherty, had been called before a Senate investigating committee but refused to appear. In McGrain v. Daugherty, decided in 1927, the Supreme Court recognized that Congress had significant power to investigate the lives and activities of private citizens in carrying out its Constitutional duty to legislate, even though the Constitution nowhere specifically grants an investigatory power to Congress. Thus, the Walsh hearings produced a significantly broader understanding of the role of Congress as an investigatory body.

The special prosecutors filed two civil cases to cancel the disputed oil leases. Both cases were appealed to the Supreme Court, which voided the disputed oil leases in 1927, on the grounds of corruption and actions without basis in law. Teapot Dome and Elk Hills were then shut down, although Elk Hills was opened during World War II. In 1976, in response to the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973–1974, Congress directed that the naval reserves be brought into full production. They were transferred to the Department of Energy in 1977. Production at Elk Hills made it one of the largest producing oil fields in North America. In 1995, President William Clinton proposed selling the Elk Hills reserve as part of his administration’s efforts to reduce the size of government and to privatize some federal functions. In 1996, Congress approved legislation that directed that Elk Hills be sold to the highest bidder. Occidental Petroleum Company took over operations there in 1998 in the largest single divestiture of federal property in the history of the US government. The Buena Vista Hills reserve was transferred to the Department of the Interior in 2005. The Department of Energy retains control of Teapot Dome, which currently produces a small amount of crude oil and natural gas and earns approximately $5 million per year for the federal government.

Robert W. Cherny is a professor of history at San Francisco State University. His books include California Women and Politics: From the Gold Rush to the Great Depression (2011) with co-editors Mary Ann Irwin and Ann Marie Wilson; American Labor and the Cold War: Unions, Politics, and Postwar Political Culture (2004) with co-editors William Issel and Keiran Taylor; and American Politics in the Gilded Age, 1868–1900 (1997).

No comments:

Post a Comment